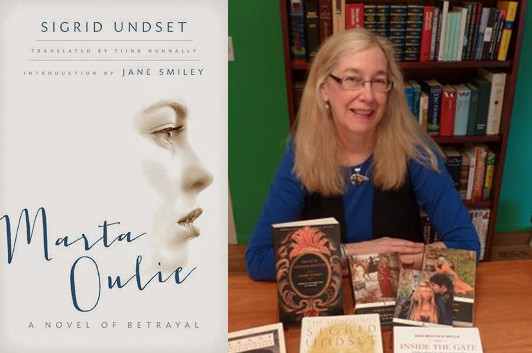

Tiina Nunnally & the Long-Awaited Debut of Sigrid Undset

photo via AATIA.org

As a translator, Tiina Nunnally has had a long-term relationship with the early 20th-century Norwegian author Sigrid Undset; you may have seen the monster-sized omnibus edition of her translation of Undset’s historical epic Kristin Lavransdatter novels that came out about a decade ago. Around that same time, Nunnally finished a translation of Unset’s first, more contemporary novel, Marta Oulie—but, as she explains, it took her a while to find someone to publish the story of a young woman in Oslo struggling against societal expectations and a confining marriage. As you can see, she was ultimately successful, and here she tells us a bit about why she took such pains to bring this novel to light for English-language readers.

This morning I went to the post office and found a card from my novelist friend Mary, who lives in California. We first met in a book club in Seattle more than twenty years ago, and since then she and I have been discussing books both on the phone and by mail—and yes, we actually still write letters to each other! Last week I sent her a copy of my translation of Sigrid Undset’s Marta Oulie because I know that Mary is a big fan of Undset’s work. And she was definitely excited to get the book. “Imagine,” she said, “until now it did not exist in English!”

And it is surprising that Undset’s first novel (from 1907) has never before appeared in English translation. After all, she won the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1928), and her epic medieval trilogy Kristin Lavransdatter as well as the four-volume Olav Audunssøn (published in English as The Master of Hestviken) have captivated readers for generations. But many people don’t realize that Undset started her literary career by writing contemporary works. The Swedish Nobel committee even acknowledged the power of Undset’s early novels and short stories by praising her ability to depict modern women “sympathetically but with merciless truthfulness… and [to] convey the evolution of their destinies with the most implacable logic.”

Since Sigrid Undset is one of my all-time favorite authors, I wanted other people to read more of her books—especially her early stories.

10 March 2014 | in translation |

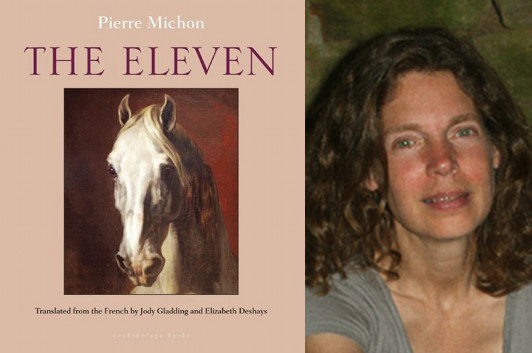

Jody Gladding & Elizabeth Deshays: Two Translators Take On The Eleven

photo via Jody Gladding

Pierre Michon’s The Eleven is the story of a French painter who never existed: Corentin, “the Tiepolo of the Terror,” so called because of his most famous work, a group portrait of the 11 members of the French Revolution’s Committee of Public Safety. This short novel is essentially a monologue in which the narrator, addressing a gentleman viewing this painting in the Louvre, delivers a fairly opinionated account of Corentin’s life and work. The Eleven is co-translated by Jody Gladding (pictured above) and Elizabeth Deshays, and so one of my first questions for them was what drew them to translate an author like Michon as a team, let alone as an individual project…

Elizabeth: How did we come to Michon? Well, I suppose that it would be more accurate to say that he came to us. Jody, you had been commissioned to translate Vies Minuscules after the original translator abdicated. You had started to look at the text and asked me for help, hoping that my many years in France would enable me to throw some light onto the first of these Small Lives. I can still remember the passage, and my bewilderment, the feeling of not knowing how to begin. Of course, we recognised and understood the words, the sentences, but from there to what he was trying to say… And who was this writer anyway? (To my shame, I had not then read any of his works). My instinctive reaction was one of rejection.

Yesterday, I reread that passage. I was astonished. What had seemed so inaccessible at that first reading? The text was immediately clear to me, I knew what every image, every metaphor was referring to.

The explanation, of course, is that, three Michon translations on, we now know the man. For Michon, though he in no conventional way could be described as writing autobiography, nevertheless always writes about himself; the obsessions, traumatisms and aspirations which make him what he is are always, at the deepest level, the real matter of his work, though it may, more superficially, take on the guise of something resembling biography (Rimbaud le Fils), legend (Contes d’Hiver) or historical novel (Les Onze).

4 March 2013 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.