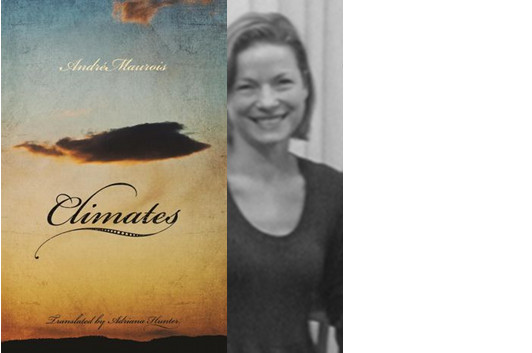

Adriana Hunter: Discovering Fresh Climates

photo: Peirene Press

Over the last decade or so, Adriana Hunter has become one of the leading English-language translators of contemporary French literature, but with Climates, she’s taken on something new, or rather something not so new—André Maurois wrote Climats in the late 1920s, and it was a bestselling sensation not just in France but throughout Europe when it was first published. (At the time, it was brought to the United States as Atmosphere of Love; in the 1980s, a new translation appeared under the title The Climates of Love.) In this guest essay, Hunter talks about the challenges she faced in making a novel that’s nearly 85 years old “fresher” while staying true to the language conventions of the era.

My “way in†to translating any book is its narrative voice. I hear a voice and get a feel for its tone, rhythms and word patterns. André Maurois’s Climates of Love was a little more complicated because there are two narrators, Philippe and Isabelle, as well as less formal extracts from Philippe’s private notebooks and from letters. On top of this, there is the question of period: Climates was written in the 1920s, and my publisher had asked me to update the prose, making it feel fresher but without anachronisms (infatuation and jealousy probably feel the same now as they did a century ago, but other sensibilities and constraints in the book are very specific to the characters’ era, and I was keen to respect these).

Having previously translated only contemporary writers, I found the question of period and anachronism an enjoyable new challenge. In Maurois’s original, even the dialogue can sound like writerly prose whereas in a lot of contemporary fiction even the prose sounds like colloquial dialogue. I wanted to strike a balance, making the prose accessible but still with the poise and restraint of another era. I hope this sentence from the first page illustrates this:

“That is the charm of new acquaintances: the hope that, in their eyes and by denying the truth, we can transform a past that we wish had been happier.â€

Which might have sounded more natural as:

“That’s what’s nice about meeting new people, you can always hope that—if you deny the truth yourself—you can make them believe your past was happier than it was.â€

This is a perfectly valid translation, but look at those modern contractions (that’s what’s), those muscular dashes around a clause and that gangling repetition of “wasâ€. It just doesn’t sound like someone from Philippe’s background in the 1920s.

10 December 2012 | in translation |

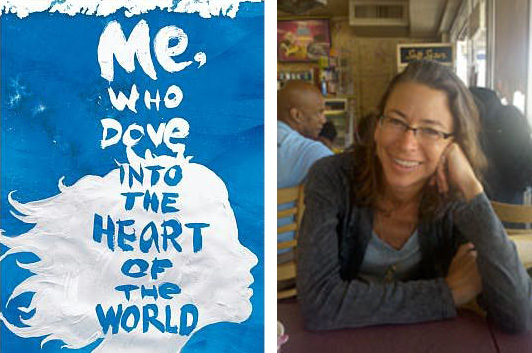

Lisa Dillman: Finding Me‘s Voice

photo via Words Without Borders

Translating a first-person narrator into English from another language can be a challenge under any circumstances, but when that narrator has a non-standard emotional and mental profile like Karen, the autistic protagonist of Sabina Berman’s Me, Who Dove into the Heart of the World, the work gets harder. Lisa Dillman rises to the occasion, though—and, in this guest essay, reminds us that when we think, before we even open a novel, that we know what it and its characters are going to be about, that’s when we’re most likely to be caught off guard by the author’s real plans.

When I first read Me, Who Dove Into The Heart of The World, I became obsessed with the idea of translating it, and a year later I was thrilled to get the opportunity to do so. The novel tells the story of Karen, a highly-functioning-autistic-cum-bluefin-tuna-industry-magnate. She starts the novel as a mute, feral, wild-child eating wet sand in Mazatlán, Mexico and ends up in a Tokyo penthouse surrounded by multiple laptops. In case it’s not immediately apparent, this is a highly unusual novel. And one I fell in love with for multiple reasons.

To begin with, there is Karen’s unique voice. She speaks—and writes—in clipped sentences devoid of “standard human” frippery. Karen is a literalist. When out on a fishing boat with an Italian sailor who claims God gave humans license to kill, she wants to see the license. She lacks inflection and eschews metaphor, euphemism and fantasy, all of which she classifies as lies used by “standard humans” in the name of deceit and self-delusion. Euphemism, for instance, is employed in order to disguise a terrible thing as a good one. Providing a run-down on her classes at college, where she studies animal husbandry, Karen gives us one of numerous examples of human idiocy, informing us that “the methods course on killing… animal species was called Meat Industry.” Throughout the novel, readers get the chance to experience Karen’s forthright, direct way of thinking, seeing and feeling the world, and this proves an excellent way to reconceive of our own “standard” modes of action and interaction through fresh eyes.

17 August 2012 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.