Tiina Nunnally & the Long-Awaited Debut of Sigrid Undset

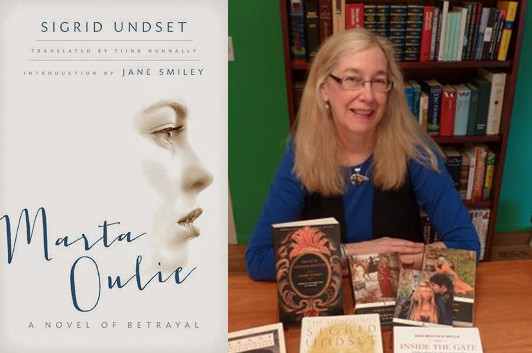

photo via AATIA.org

As a translator, Tiina Nunnally has had a long-term relationship with the early 20th-century Norwegian author Sigrid Undset; you may have seen the monster-sized omnibus edition of her translation of Undset’s historical epic Kristin Lavransdatter novels that came out about a decade ago. Around that same time, Nunnally finished a translation of Unset’s first, more contemporary novel, Marta Oulie—but, as she explains, it took her a while to find someone to publish the story of a young woman in Oslo struggling against societal expectations and a confining marriage. As you can see, she was ultimately successful, and here she tells us a bit about why she took such pains to bring this novel to light for English-language readers.

This morning I went to the post office and found a card from my novelist friend Mary, who lives in California. We first met in a book club in Seattle more than twenty years ago, and since then she and I have been discussing books both on the phone and by mail—and yes, we actually still write letters to each other! Last week I sent her a copy of my translation of Sigrid Undset’s Marta Oulie because I know that Mary is a big fan of Undset’s work. And she was definitely excited to get the book. “Imagine,” she said, “until now it did not exist in English!”

And it is surprising that Undset’s first novel (from 1907) has never before appeared in English translation. After all, she won the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1928), and her epic medieval trilogy Kristin Lavransdatter as well as the four-volume Olav Audunssøn (published in English as The Master of Hestviken) have captivated readers for generations. But many people don’t realize that Undset started her literary career by writing contemporary works. The Swedish Nobel committee even acknowledged the power of Undset’s early novels and short stories by praising her ability to depict modern women “sympathetically but with merciless truthfulness… and [to] convey the evolution of their destinies with the most implacable logic.”

Since Sigrid Undset is one of my all-time favorite authors, I wanted other people to read more of her books—especially her early stories.

I had already translated one “modern” work by Undset: her novel Jenny from 1911, which is the gripping (some might say “harrowing”) story of a talented Norwegian painter whose yearning for love causes her to betray all her own ambitions and ideals. It’s also an honest depiction of a young woman’s love life, which scandalized Norway when the book was first published.

As with my translation of Kristin Lavransdatter, I viewed my work on Jenny as a “restoration project.” The previous English translation (from 1921) failed to capture the clarity or beauty of the author’s style, and some passages had been censored, perhaps considered too overtly sexual for the reading public at the time. My goal as a translator was to bring the novel back to life in English—to regain the enthusiasm of those readers who had been disappointed by the clumsy wording and flat tone of the earlier translation, and to attract a whole new group of readers to Undset’s work.

With Marta Oulie, my concerns were a little different. First, it was Sigrid Undset’s debut novel, and I’ve always been fascinated to see how the early works of great authors can reveal the glimmerings of future genius. So I wanted the novel to have as strong an impact in English as it does in Norwegian. Second, no one had ever seen this book in English before, so I felt an even greater responsibility to convey as accurately as possible the spare style and emotional force of the original.

The fact that the story is written in first person, and in the format of a private diary, made my job even more challenging. There is a sense of depth and immediacy that is not always as prevalent in a third-person narrative.

I often say that translating is rather similar to acting. The translator has to immerse herself in the “voice” of the text, giving up her own voice in the process. Of course it’s impossible to become a hundred percent invisible, because every translator brings her own background and experiences to the work. But with practice—by paying attention to such things as rhythm, pacing, word choice, and repetition—a translator can learn to take on the “role” of the book.

Translating Marta Oulie was particularly demanding because the voice of the title character is so distinct and compelling—matter-of-fact in some passages, desperate and guilt-ridden in others. And I especially wanted to capture in English what my friend Mary so aptly identified as the “sensuousness” of this particular novel.

Although I finished my translation of both Marta Oulie and a half dozen of Undset’s equally remarkable short stories in 2004 (thanks to a Translation Fellowship from the NEA), I couldn’t find a publisher for these works. I put the manuscript in my closet, and there it sat until the spring of last year, when a confluence of events led me to the University of Minnesota Press. I want to thank editor Erik Anderson, in particular, for recognizing the literary quality and importance of Sigrid Undset’s early fiction. I am thrilled to see her first novel now made available to readers of English in such a handsome edition.

In the card that I received this morning, my friend Mary said that she had put aside another book she was reading to begin Marta Oulie immediately, and that she was reading Undset’s novel almost too fast “because her writing style is so lovely.” That made me very happy. There is no greater reward for a translator than to know that a book has managed successfully to make the transition from one language to another, and is continuing to “live” in the minds and hearts of readers.

10 March 2014 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.