You Are Capable of Telling Better Stories

I should confess at the onset: I’ve swiped the title of today’s newsletter from GB “Doc†Burford and his excellent essay, “You Are Capable of Writing Better Horror Stories.†And though I’m going to tell you a little bit about it here, I strongly encourage you to go read the whole thing.

Burford is a video game consultant and “narrative designer,†and his essay springs out of a sense of frustration that came from playing a number of video games that all felt the same:

“So, there’s this protagonist, and he’s just arrived at an isolated location. Maybe there are some people around, but usually not many. It’s far from civilization, desolate, probably dark. He cannot get help… [T]hen lo and behold, some spooky stuff happens, it’s horrifying, and then oh no, suddenly it’s all a metaphor for the guilt he feels over some bad stuff he did or was involved in a long time ago.â€

I get where he’s coming from, because when I stumbled onto his essay, I had just finished reading my second horror novel in a row that started out with some exquisitely tense variations of Lovecraftian horror spilling over into the real world in all their vivid… well, glory’s not the right word, but you know what I mean. Anyway, they start out that way, but they both build up to what’s basically a climactic action-movie shootout with the Big Boss and his toughest minions, and though much is extracted from our protagonists they somehow squeak through, wounded but perhaps a bit wiser about their ultimate standing in the universe.

I mean, I suppose there’s not much else you can do to end this kind of story, unless you want to end it the way Lovecraft did, with your protagonist’s rational mind overwhelmed by the sheer cosmic terror of the Old Ones. But when everybody’s doing it, as with the amnesiac or cagey protagonist forced to confront their horrific past, it becomes very obvious very quickly.

Burford has much to say that’s specific to the horror genre, but much of it also applies to any mode of storytelling, and this is one quote that stopped me in my tracks:

“For me, great fiction is as Tarkovsky says, a way to harrow someone’s soul, preparing them for death. It is a means of granting us emotional experience and hopefully release.â€

I wish I had a more comprehensive understanding of Tarkovsky, so I could speak that in its context, but for now here’s the original quote, from Sculpting in Time:

“The allotted function of art is not, as is often assumed, to put across ideas, to propagate thoughts, to serve as example. The aim of art is to prepare a person for death, to plough and harrow his soul, rendering it capable of turning to the good.â€

It reminded me of a line from Harold Bloom that’s stuck with me since reading it a quarter-century ago: “All that the Western Canon can bring one is the proper use of one’s own solitude, that solitude whose final form is one’s confrontation with one’s own mortality.†Bloom doesn’t even profess to care about becoming “capable of turning to the good†through experiencing great art; for him, that experience only “enables us to learn how to talk to ourselves and how to endure ourselves.â€

In my younger days, I might have leaned toward that position, or at least embraced it ironically in a loud and swaggering manner that probably made me insufferable at parties. Now, to the extent that I understand that fragment of Tarkovsky, I think he’s probably on to something.

That’s not to say I believe every novel should be a transcendent experience—more like every novel should try to offer you the opportunity to see something in this world, through emotional engagement, you hadn’t seen before, and once you’ve seen it, you can no longer continuing living quite the way you did.

Or, as I’ve written elsewhere, every novel makes a philosophical argument about the world—it professes to show us a way of living, a way of responding to certain stimuli in the world around us. It can be a negative argument (“all is lostâ€), or a positive argument (“things work outâ€), an ostensibly neutral argument (“and so it goesâ€) or an optimistic argument (“wouldn’t it be great if…?â€).

Horror fiction tends to spend a lot of time in “all is lost†territory, although at least half the time things work out by the end. (When they don’t, and so it goes.) Until you get to a hard-won resolution, though, the horror narrative is filled with harrowing uncertainty about whether good will prevail over evil—or whether the human spirit will, for the time at least, prevail over entropy.

But even romance fiction, which is in many ways the opposite of horror in that it’s explicitly, from the beginning, about fulfilling the vision of an enduring and satisfying relationship, tends to work best when the narrative path is full of harrowing uncertainty about whether that relationship will come together. Yes, everything works out, and the romance reader picks up the novel knowing everything will work out, but we still like to be made to worry, just a little bit, about how those lovebirds are going to pull it off, so we can be all the more satisfied when they do have their final clinch.

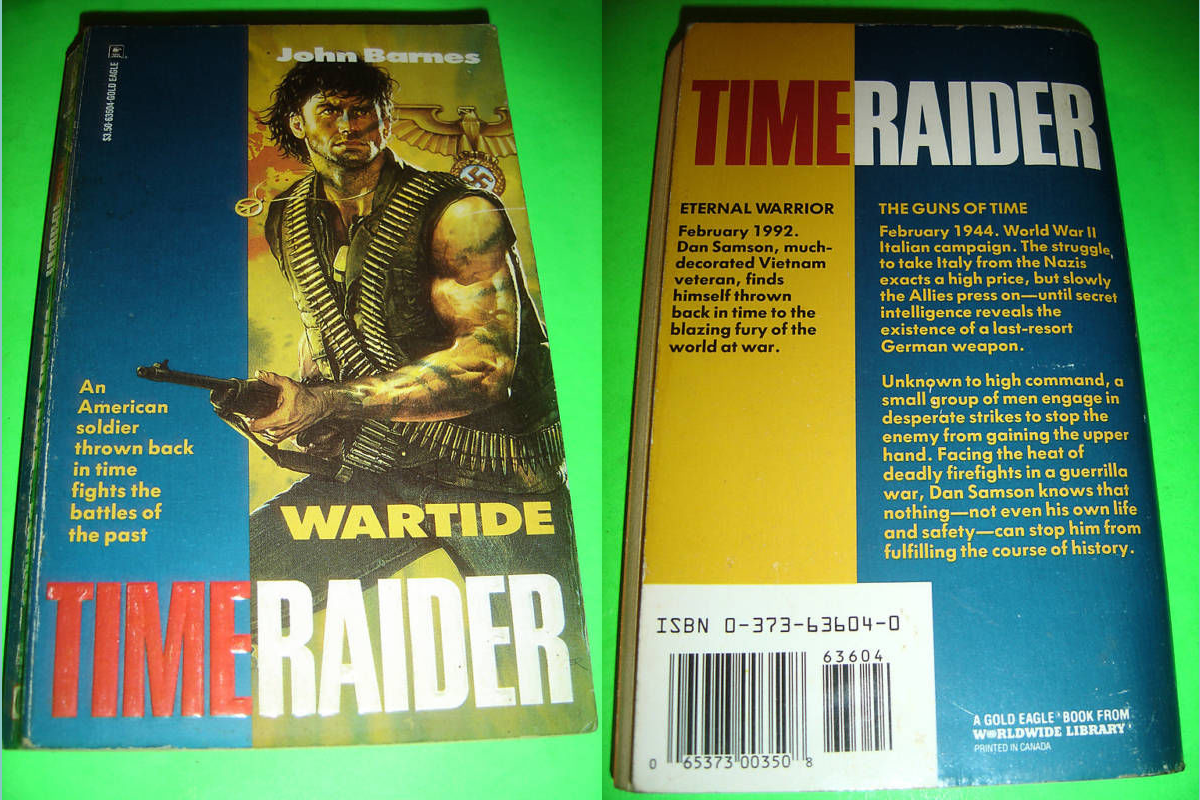

I posted an abbreviated version of the preceding thoughts on Twitter right after reading Burford’s essay, and then the science fiction author John Barnes shared a story from his career that… I’m still in awe, really. Here’s how it starts: “[The] fourth novel I ever finished was WARTIDE, a time-travel men’s action adventure for which [the] title and cover art had already been done and then the contracted writer had bailed with nothing written.â€

“I wrote Wartide in 8 days,†Barnes continues. “It is my shortest novel, my most violent, unquestionably my worst.†And yet… two years after it had come out, he got a letter from an Air Force sergeant recuperating in a burn unit, who found inspiration in Barnes’ slapped-together stories of a soldier sent back in time to redeem his past lives. That letter blossomed into a correspondence, and Barnes was able to see, over time, how the sergeant was able to transform his own life.

“To this day,†Barnes wrote, “I think that if I had only known the book was going to matter to anybody, broke and desperate though I was, I might have done a second draft. Also that one should always write as if a book might mean something or matter to somebody, because, unlikely as it may seem, it’s always possible that it will.â€

That feels like a good note to end this on, and send you to your own writing.

(Although, if you have an Xbox or Steam, you might want to check out Doc Burford’s new video game, Adios, in which you play a pig farmer who has been disposing of dead bodies for the mob but has decided to stop doing so, and must explain his decision to the professional killer with whom he’s worked most closely over the years. Burford describes the tone of Adios as “melancholy†rather than horror, and when it comes to my computer platform, I believe I will give it a try. Also, remember how I said at the top of the newsletter you should read his whole essay? You really should.)

Wartide cover art: BestLittleBookHouse.com

This post was first published in “Destroy Your Safe and Happy Lives,” a newsletter I’ve been writing since 2018. If you’d like to subscribe and get every new installment delivered to your email (free!), you can do that here.

27 March 2021 | newsletter |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.