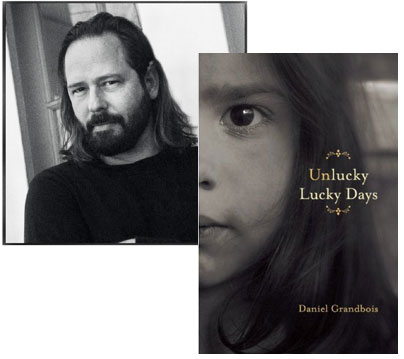

Daniel Grandbois and the Trickster Gods of Short-Short Fiction

You can read just about any of the stories in Daniel Grandbois’s Unlucky Lucky Days in under three minutes; while a few spill over onto a second page, most are just a few paragraphs. Here, for example, is the entirety of “The Tunnel”:

A man and a woman stepped into a tunnel. It was lighter inside than they had expected. In fact, the deeper they went the lighter it became until the light was so bright that it blinded them both.

The worlds in which these stories take place bear little resemblance to the ones in which their readers live… but there may be other relations to consider. In this essay, Grandbois discusses the magic he’s found in such tightly compressed narratives.

As Cairn terriers were bred to get into the crannies of Scottish cairns and root out little beasties, the short forms of literature scare such vermin of the human mind into the light. These places can’t be reached by the Great Danes, English Foxhounds, and French Poodles of the long forms, to whom the frantic little terrier may look like only a plaything. A step back reveals it is needed no less equally by the man.

Long forms make their homes most often in what is called realism, a natural setting for something of their size. Planets, for example, live, by comparison, in a more realistic place than do subatomic particles—at least when tallied by human common sense. Yet, each locale is buzzing with indispensible activity. In many ways, the short forms, like the subatomic realm, are the trickster gods, come to mess up the hair of anyone believing the pinnacles of artistry or knowledge are within reach. They expose the conceits of realism, not with malice (when working at their best) but with humor—a wink, a nod, or a hairy-assed moon—for we are all in this together.

“Everything you can imagine is real,” said Picasso; it’s become my standard answer to questions framed to suggest high literary art can be summoned only by the incantations of realism and the character-driven long forms. Misconceptions like these keep the literary arts decades behind the visual and the auditory, and light-years behind scientific discovery.

25 August 2008 | selling shorts |

Christopher Meeks on Lorrie Moore’s Profound Humor

I started reading the short stories in Christopher Meeks‘s Months and Seasons on a recent plane ride, and was struck by his quiet sense of humor—he’s not a guy who works for laughs, necessarily, but when his characters get to bickering with one another, little spikes emerge from their interactions. In this essay, he explains how he learned to let that part of his writing voice flourish thanks to the example set by one of our greatest contemporary short story authors.

Like many people of my generation, I wanted to write great stories, important stories—stories that made me rich. Then along came reality: I receive little or no money when my stories are published, but I get two copies of any literary journal I’m in. While that hasn’t helped pay my son’s college bills, I’ve nonetheless been awed that I’ve made it into the journals. Also, publication has helped me rediscover my sense of humor.

When I started, great stories, of course, had to be serious. Woody Allen has had this complex, too, which is why he made Interiors and Cassandra’s Dream. He’s wanted to be Begmanesque—as others have been desperately trying to mimic his funny movies and be Allenesque.

I wanted to be Literary with a capital L, but humor kept creeping into my stories. I’d write the first draft, not worrying about my voice, and then later I’d excise humor, such as a character’s funny quip, thus maintaining what I thought was literary decorum. I might change a line of dialogue from, “You like her? She has guppy lips. Her hands are pound cakes” to “You like her? She’s plain.”

18 May 2008 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.