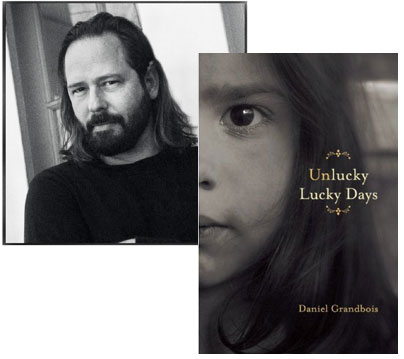

Daniel Grandbois and the Trickster Gods of Short-Short Fiction

You can read just about any of the stories in Daniel Grandbois‘s Unlucky Lucky Days in under three minutes; while a few spill over onto a second page, most are just a few paragraphs. Here, for example, is the entirety of “The Tunnel”:

A man and a woman stepped into a tunnel. It was lighter inside than they had expected. In fact, the deeper they went the lighter it became until the light was so bright that it blinded them both.

The worlds in which these stories take place bear little resemblance to the ones in which their readers live… but there may be other relations to consider. In this essay, Grandbois discusses the magic he’s found in such tightly compressed narratives.

As Cairn terriers were bred to get into the crannies of Scottish cairns and root out little beasties, the short forms of literature scare such vermin of the human mind into the light. These places can’t be reached by the Great Danes, English Foxhounds, and French Poodles of the long forms, to whom the frantic little terrier may look like only a plaything. A step back reveals it is needed no less equally by the man.

Long forms make their homes most often in what is called realism, a natural setting for something of their size. Planets, for example, live, by comparison, in a more realistic place than do subatomic particles—at least when tallied by human common sense. Yet, each locale is buzzing with indispensible activity. In many ways, the short forms, like the subatomic realm, are the trickster gods, come to mess up the hair of anyone believing the pinnacles of artistry or knowledge are within reach. They expose the conceits of realism, not with malice (when working at their best) but with humor—a wink, a nod, or a hairy-assed moon—for we are all in this together.

“Everything you can imagine is real,” said Picasso; it’s become my standard answer to questions framed to suggest high literary art can be summoned only by the incantations of realism and the character-driven long forms. Misconceptions like these keep the literary arts decades behind the visual and the auditory, and light-years behind scientific discovery.

My stories bubble up from places in my mind or places my mind attaches to that don’t know how to use words. As best I can, I translate them into the current usage of the English language, one that may be around for another few hundred of our circles around the sun, at most. The stories that matter to me are those capable of rewiring the nervous system, of opening wormholes to broader perception, like Zen koans.

Folk tales and children’s tales, especially those of yesteryear—”The Tales of Uncle Remus,” “Just So Stories,” George MacDonald’s and Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales—can do this as well as any, can lay bare the bizarre, often contradictory workings of this electric lump of gray matter, which thinks back through ages oblivious of me. In adult literature, the brief absurdities of Beckett, Edson, Kharms, Calvino, and Pinget reveal more about what it’s like to inhabit this strange body with these mad monkeys in the mind than any number of tomes devoted to the gradual development of character and plot.

The realm of presently-formed human animals interacting with each other on this particular moss-covered pebble, which drifts silently through a universe expanding at rates we cannot account for, is certainly worthy of our attention, but it is also rather small compared to the very real, forward-, backward-, and sideways-spinning realms of the imagination.

25 August 2008 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.