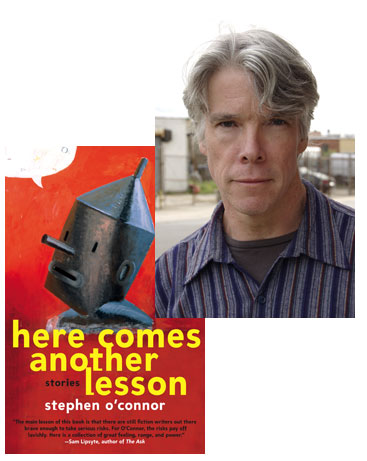

Stephen O’Connor & the Constant Flux of “The Country Doctor”

One of the things I love about the stories in Stephen O’Connor’s new collection, Here Comes Another Lesson, is the way the scenes play out in staccato bursts—check out “Ziggurat,” in which a Minotaur wandering through a postmodern Labyrinth happens upon a teenage girl who isn’t nearly as terrified of him as perhaps she ought to be, and you’ll see what I mean. (The story right after it in the collection, “White Fire,” deploys much the same tactic in a more psychologically realistic fashion, as a soldier coming home from Iraq struggles to get his life back the way it was; it’s so effective that you might miss the sheer brutality of his failure the first time you read through, only to have it hit you at the story’s end. And then there’s the sequence of stories sprinkled throughout the book featuring Charles, “the professor of atheism,” who fumbles through a variety of scenarios that sorely test his lack of belief in the divine. Whether he’s writing in a surrealist or a realist mode, there’s a dream-like quality to O’Connor’s prose that will remind many readers of Kafka—no accident, as O’Connor reveals in this essay about the inspiration he found in a particulary vivid Kafka short story.

The first time I read Franz Kafka’s “A Country Doctor”—at around age twelve—I had the distinct impression that I was discovering myself, that in his language and images, and in particular in his always surprising juxtapositions and narrative turns, I was experiencing something essential about the way I was and wanted to be in this world.

The story opens with a long, breathless sentence:

“I was in a great perplexity; I had to start on an urgent journey; a seriously ill patient was waiting for me in a village ten miles off; a thick blizzard of snow filled all the wide spaces between him and me; I had a gig, a light gig with big wheels, exactly right for our country roads; muffled in furs, my bag of instruments in my hand, I was in the courtyard all ready for the journey; but there was no horse to be had, no horse.”

By the time I reached the end of this sentence, I already had a sense of the terrific understatement that its first six words would soon turn out to be. I could feel the narrator’s barely suppressed hysteria through his repetitions (“a gig, a light gig;” “no horse to be had, no horse”), through the intensity of his adjectives and adverbs (“great,” “urgent,” “seriously”), and in the way six short sentences had been jumbled into one outburst. What is more, I had a sense that neither the narrator nor the world in which he existed was quite normal. Why had he bothered, for example, to emphasize what we would have expected: that his gig was suitable for the local terrain? And why was he waiting in his frigid courtyard when, not merely was his gig still unhitched, there was no horse for it? And then there was the simple oddness of a doctor, a man of science, alone, “muffled in furs,” passively waiting for fate to change, and the peculiar implication that, since the blizzard only “filled all the wide spaces between” one place and another, it had somehow stayed outside the boundaries of each.

This was a world in which things could go very wrong (people became seriously ill, horses vanished) and in which one was deprived even of the consoling expectation that people and things would behave in a normal, predicable and rational way—a world in which one could accept that the doctor’s “perplexity” was “great” indeed, and expect that it would only become greater.

23 August 2010 | selling shorts |

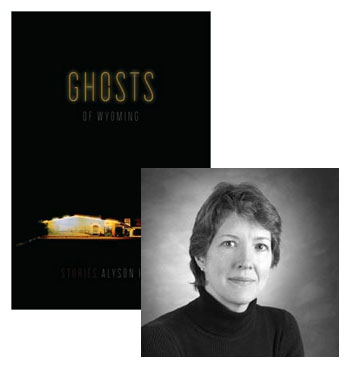

Alyson Hagy: The Strange Side Effects of “Paper Pills”

The eight stories in Alyson Hagy’s Ghosts of Wyoming may all be set in the same state, but each one has its own way of navigating that existential landscape—some stories are set in the late 19th-century, and others could have taken place earlier today; some characters are desperate to escape, while others have reached the end of their road. In her guest essay for Beatrice, Hagy has zeroed in on a story from a collection that’s even more intensely focused on exploring a single location.

It’s a strange story, and it revels in its strangeness. It doesn’t bother with scene or traditional dramatic structure. It makes no attempt to explain itself or to achieve the predictable “balance” between character development and style that I stupidly used to claim was the righteous goal of a short story.

It’s as twisted as the “twisted little apples” that serve as its central metaphor, those flawed fruits left behind at harvest, the cast-offs that harbor “sweetness” amid their deformity if you know just where to bite.

I like flawed apples.

Winesburg, Ohio is a book I go back to again and again. It’s an unruly creation. Some of its narratives are as thwarted and stunted as the characters they feature. The book has none of the certain authority of Flannery O’Connor’s A Good Man is Hard to Find. It contains none of the dash and dazzle of Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time. Yet it’s a book I can’t shake, a town I can’t forget, the product of an artistic faith and fearlessness I want to transfuse into my own faded veins.

Who the hell writes stories like “Paper Pills” anymore?

30 July 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.