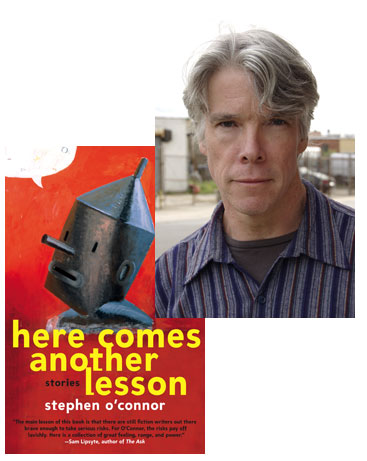

Stephen O’Connor & the Constant Flux of “The Country Doctor”

One of the things I love about the stories in Stephen O’Connor’s new collection, Here Comes Another Lesson, is the way the scenes play out in staccato bursts—check out “Ziggurat,” in which a Minotaur wandering through a postmodern Labyrinth happens upon a teenage girl who isn’t nearly as terrified of him as perhaps she ought to be, and you’ll see what I mean. (The story right after it in the collection, “White Fire,” deploys much the same tactic in a more psychologically realistic fashion, as a soldier coming home from Iraq struggles to get his life back the way it was; it’s so effective that you might miss the sheer brutality of his failure the first time you read through, only to have it hit you at the story’s end. And then there’s the sequence of stories sprinkled throughout the book featuring Charles, “the professor of atheism,” who fumbles through a variety of scenarios that sorely test his lack of belief in the divine. Whether he’s writing in a surrealist or a realist mode, there’s a dream-like quality to O’Connor’s prose that will remind many readers of Kafka—no accident, as O’Connor reveals in this essay about the inspiration he found in a particulary vivid Kafka short story.

The first time I read Franz Kafka’s “A Country Doctor”—at around age twelve—I had the distinct impression that I was discovering myself, that in his language and images, and in particular in his always surprising juxtapositions and narrative turns, I was experiencing something essential about the way I was and wanted to be in this world.

The story opens with a long, breathless sentence:

“I was in a great perplexity; I had to start on an urgent journey; a seriously ill patient was waiting for me in a village ten miles off; a thick blizzard of snow filled all the wide spaces between him and me; I had a gig, a light gig with big wheels, exactly right for our country roads; muffled in furs, my bag of instruments in my hand, I was in the courtyard all ready for the journey; but there was no horse to be had, no horse.”

By the time I reached the end of this sentence, I already had a sense of the terrific understatement that its first six words would soon turn out to be. I could feel the narrator’s barely suppressed hysteria through his repetitions (“a gig, a light gig;” “no horse to be had, no horse”), through the intensity of his adjectives and adverbs (“great,” “urgent,” “seriously”), and in the way six short sentences had been jumbled into one outburst. What is more, I had a sense that neither the narrator nor the world in which he existed was quite normal. Why had he bothered, for example, to emphasize what we would have expected: that his gig was suitable for the local terrain? And why was he waiting in his frigid courtyard when, not merely was his gig still unhitched, there was no horse for it? And then there was the simple oddness of a doctor, a man of science, alone, “muffled in furs,” passively waiting for fate to change, and the peculiar implication that, since the blizzard only “filled all the wide spaces between” one place and another, it had somehow stayed outside the boundaries of each.

This was a world in which things could go very wrong (people became seriously ill, horses vanished) and in which one was deprived even of the consoling expectation that people and things would behave in a normal, predicable and rational way—a world in which one could accept that the doctor’s “perplexity” was “great” indeed, and expect that it would only become greater.

The brilliance of Kafka’s best stories is that they always exceed the expectations they encourage. We might assume that the doctor would eventually find a horse, for example, but probably not that he should do so by kicking open a pigsty door in frustration and discovering two magnificent horses and a groom inside. Nor are we likely to expect that this groom with an “open blue-eyed face” would exert a demonic force over the doctor’s household, biting the servant girl on her cheek, then sending doctor, gig and horses off into a blinding storm so that he might rape the girl.

The story proceeds from one arresting image to another: The doctor discovers that his possibly malingering patient has a huge wound in his side infested by finger-thick worms. The boy’s parents and neighbors tiptoe into his room, strip the doctor naked and put him into bed with the boy, who whispers in his ear, “I have very little confidence in you.” And in the story’s final image, we find the doctor, still naked, astride one of the horses, trudging though “snowy wastes,” knowing he will never make it home, and never be able to “make good” the string of events that commenced with a “false alarm on a night bell.” Each of these images is all but unpredictable on the basis of what precedes them, but each has a psychological resonance within the context of the story that makes it seem inevitable and complexly truthful.

Everything in Kafka’s stories is secretly something else, or is on the verge of becoming something else. The world is in constant flux, never susceptible to any one interpretation, always mysterious, always surprising, often comical even as it is tragic. Again and again, Kafka’s characters and readers are thrown into perplexity—but perplexity is only the sudden awareness that one’s ordinary understandings don’t apply, and so it is an opening up to the world, a form of liberation and a precursor to revelation. While Kafka’s characters know very little joy, and lead lives entirely determined by implacable if absurd and incomprehensible laws, the sensibility that created those characters is wonderfully free, ever alert to the world’s multiplicity and entirely unfettered by conventional understandings. Kafka as a man may have been as hemmed in and unhappy as his characters, but as a writer he was, I believe—if only in isolated moments—possessed by the joys of discovery and creation.

For reasons that, perhaps, I don’t want to investigate too thoroughly, I have always felt a wary affinity for Kafka’s bleak vision. But what most attracted me to his stories was the pleasure he found in perplexity, his passion for those places where no accepted truths applies, where everything is indefinite, atremble with possibility, and therefore as close to the real as we are likely to come. I remember my excitement the first time I finished “A Country Doctor.” I wanted to rush to my desk and write my own version of the story. I probably didn’t. Sitting in one place was a low-grade torture for me at age twelve. But still, I knew exactly what kind of writer I wanted to become. And while I can’t claim that I will ever be remotely capable even of approaching Kafka’s genius, I can say that I am eternally grateful to him for having shown me a way of being in this world, and for having opened me to life’s manifold and beautiful mystery.

23 August 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.