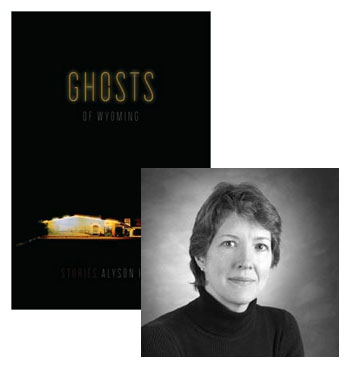

Alyson Hagy: The Strange Side Effects of “Paper Pills”

The eight stories in Alyson Hagy’s Ghosts of Wyoming may all be set in the same state, but each one has its own way of navigating that existential landscape—some stories are set in the late 19th-century, and others could have taken place earlier today; some characters are desperate to escape, while others have reached the end of their road. In her guest essay for Beatrice, Hagy has zeroed in on a story from a collection that’s even more intensely focused on exploring a single location.

It’s a strange story, and it revels in its strangeness. It doesn’t bother with scene or traditional dramatic structure. It makes no attempt to explain itself or to achieve the predictable “balance” between character development and style that I stupidly used to claim was the righteous goal of a short story.

It’s as twisted as the “twisted little apples” that serve as its central metaphor, those flawed fruits left behind at harvest, the cast-offs that harbor “sweetness” amid their deformity if you know just where to bite.

I like flawed apples.

Winesburg, Ohio is a book I go back to again and again. It’s an unruly creation. Some of its narratives are as thwarted and stunted as the characters they feature. The book has none of the certain authority of Flannery O’Connor’s A Good Man is Hard to Find. It contains none of the dash and dazzle of Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time. Yet it’s a book I can’t shake, a town I can’t forget, the product of an artistic faith and fearlessness I want to transfuse into my own faded veins.

Who the hell writes stories like “Paper Pills” anymore?

The story is purportedly about Doctor Reefy. “He was an old man with a white beard and huge nose and hands. Long before the time during which we will know him, he was a doctor and drove a jaded white horse from house to house through the streets of Winesburg… Winesburg had forgotten the old man,” Anderson writes, “but in Doctor Reefy were the seeds of something very fine.” Reefy is a bedraggled eccentric, a frayed fellow who fills his pockets with scraps of paper upon which he has written his philosophical musings. We never see what is written on those scraps. They go on to become “little hard round balls” that are eventually dumped out onto a floor. The emotional center of the story, however, is occupied by the unnamed young woman whom Reefy suddenly marries, a wealthy orphan who comes to the doctor because she “is in the family way.” The woman, like so many of Anderson’s characters, has become trapped in the webs of sexual desire and courtship. She is repelled by the hypocrisy of a suitor who preaches virginity. She responds to the attentions of a “black-haired boy with large ears” who acts rather than talks. She is rewarded with a scandalous pregnancy.

Then, just when we think the story is revved up to explore the future of the mismatched couple, Reefy and his much-younger wife, Anderson pulls the rug out from under us. “In the fall after the beginning of her acquaintanceship with him she married Doctor Reefy and in the following spring she died.” The story tosses the wife, and every narrative opportunity she represents, overboard. Immediately. The final gnarled paragraph suggests the wife may have died after being subjected to “all of the odds and ends of thoughts” Doctor Reefy has “scribbled on [his] bits of paper.”

Who gives up that kind of opportunity to explore character and consequence? A writing workshop would raise its voices in protest, wouldn’t it? Anderson has set up a big windmill of a story. Why doesn’t he have the courage, or the patience, to turn its blades?

Maybe Anderson wasn’t interested in follow through. Maybe he believed he had made his point. Both Reefy and the young woman have turbulent and demanding interior lives. They are not who they seem to be on the surface. More importantly, they are not who they are expected to be—not within the constraints of society. Once that fact (which is tragically common in Anderson’s Winesburg) has been queerly, and specifically, established by Anderson, the story has done its duty.

And I love it. “Paper Pills” is so tilted, so skewed, so mashed into its own odd little corners. It’s also memorable. Unforgettable. I find it as alluring as those other skewed and inexplicable stories I read as a child—the ones from the Bible. It’s this kind of misfit tale that still prods me to explore human behavior for myself as I ask: “What next? What next? What next?”

30 July 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.