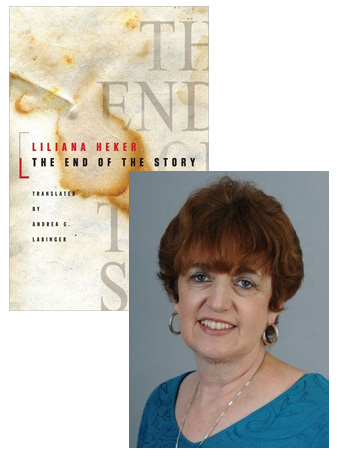

Andrea G. Labinger: The Story Continues

Liliana Heker’s The End of the Story is a powerful novel about Argentinean politics, a novel which sparked much controversy when it was published in 1996—particularly for its portrayal of a revolutionary who abandons her politics under torture and becomes an active collaborator with the ruling junta. Andrea G. Labinger, who’s translated many works by Latin American authors, wrote in a previous essay (see the link below) that she decided to take on The End of the Story “because I was attracted to its complexity as well as to the originality of Heker’s style;” it’s precisely because the novel’s political and literary tensions aren’t neatly resolved that it’s such a compelling story. In this essay, Prof. Labinger discusses some of the other questions she needed to address in formulating her approach to Heker’s prose.

There’s something vertiginous about writing an essay about translating a book about writing a book about the impossibility of telling a story. Too many “abouts,” for one thing. For another, as one perceptive reader of The End of the Story recently observed, the author grants few concessions to the reader. As is the case with most postmodern fiction, Liliana Heker makes us work for it: the complexity of her syntax only serves to intensify the multiplicity of narrative voices, dizzying time shifts, and moral ambiguity of the unsettling tale she has chosen to tell, like a tragic theme with variations, over and over again.

18 June 2012 | in translation |

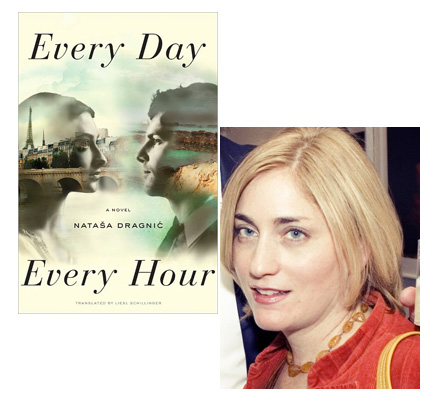

Liesl Schillinger: Literary Translation as Focused Play

Some of you may know Liesl Schillinger as a critic for the New York Times Book Review, or seen her byline on cultural essays and articles at various other publications. She’s also a literary translator, and she spent much of last year “tweaking and ‘sanding'” an English-language edition of the debut novel by Croatian-born Nataša Dragnić, Every Day, Every Hour. The title comes from the Pablo Neruda poem “If You Forget Me,” which should give you some idea of how romantic this decades-spanning story will be—and, in this guest essay, Liesl explains a bit more about why she was so drawn to translate it for English-language readers.

I’ve translated short stories many times before—always by living authors, though I never consulted them during the translation process—but this was my first book-length translation, and the first time that the author and I discussed wording choices along the way. I worried that, given Nataša Dragnić’s proficiency in English, if I translated glücklich as “happy,” for example, rather than “lucky” (both meanings are possible), she might think I was a moron. But I knew I had an instinct for what language would go over best with English-speaking readers, and trusted that this instinct would see me through. I couldn’t let anxiety hamper my work. I believed in the novel, and in my ability to convey its emotion and vitality.

The book came to my attention serendipitously. An editor friend returned from Frankfurt in 2010 with a copy of Jeden Tag, Jede Stunde in his suitcase. It had been the talk of the Frankfurt Book Fair, he said. Would I look it over and let him know if I thought it had potential here? Reading it in German, I cried many times—the tears that come when you read or watch “The English Patient,” or “Romeo and Juliet,” or any book, play or opera about star-crossed love. Set in a Croatian seaside village and in Paris, and spanning several decades, it told the poignant and passionate tale of two creative people̶a strong-willed woman and a weak-willed man—who loved each other but couldn’t make it work. I wholeheartedly endorsed the book, and agreed to translate it.

27 May 2012 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.