Liesl Schillinger: Literary Translation as Focused Play

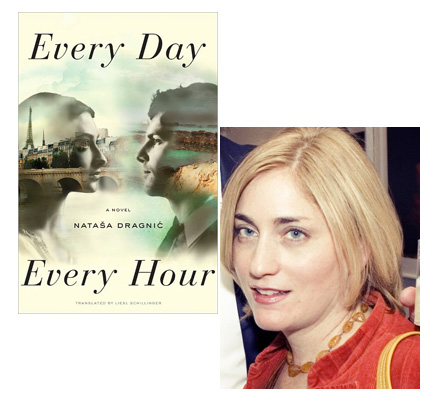

Some of you may know Liesl Schillinger as a critic for the New York Times Book Review, or seen her byline on cultural essays and articles at various other publications. She’s also a literary translator, and she spent much of last year “tweaking and ‘sanding'” an English-language edition of the debut novel by Croatian-born Nataša Dragnić, Every Day, Every Hour. The title comes from the Pablo Neruda poem “If You Forget Me,” which should give you some idea of how romantic this decades-spanning story will be—and, in this guest essay, Liesl explains a bit more about why she was so drawn to translate it for English-language readers.

I’ve translated short stories many times before—always by living authors, though I never consulted them during the translation process—but this was my first book-length translation, and the first time that the author and I discussed wording choices along the way. I worried that, given Nataša Dragnić’s proficiency in English, if I translated glücklich as “happy,” for example, rather than “lucky” (both meanings are possible), she might think I was a moron. But I knew I had an instinct for what language would go over best with English-speaking readers, and trusted that this instinct would see me through. I couldn’t let anxiety hamper my work. I believed in the novel, and in my ability to convey its emotion and vitality.

The book came to my attention serendipitously. An editor friend returned from Frankfurt in 2010 with a copy of Jeden Tag, Jede Stunde in his suitcase. It had been the talk of the Frankfurt Book Fair, he said. Would I look it over and let him know if I thought it had potential here? Reading it in German, I cried many times—the tears that come when you read or watch “The English Patient,” or “Romeo and Juliet,” or any book, play or opera about star-crossed love. Set in a Croatian seaside village and in Paris, and spanning several decades, it told the poignant and passionate tale of two creative people̶a strong-willed woman and a weak-willed man—who loved each other but couldn’t make it work. I wholeheartedly endorsed the book, and agreed to translate it.

The Frankfurt Book Fair has played a role in my translating choices before now. In 2005, on the plane back to New York from “die Messe,” as it’s called, I opened the last of some 60 books I’d scooped up from German publishers during the trip, hoping to find something that could “cross over” to American audiences. At last, I found one. It was a slim volume of stories by Bernd Lichtenberg, called One of Many Ways to Look the Tiger in the Eye. Lichtenberg co-wrote the 2003 German movie Goodbye, Lenin—about a brother and sister in Berlin who try to shield their mother (who has just awoken from a coma) from the life-threatening shock that the Wall has come down, and that “East Germany” as a country is over. One of Lichtenberg’s new stories, “Whakatane Calling,” immediately drew me. Wrenching, matter-of-fact and innocent, it was an account by a fourteen-year-old narrator of the two summer weeks when his father was dying, his mother was falling apart, his older and younger siblings were caught up in their own coming-of-age crises, and he himself detached from the catastrophe by talking to strangers on his father’s CB radio, pretending to be a sheep farmer from Whakatane, New Zealand. I translated it into English before the plane landed at JFK, and published it a few months later in Tin House. It was an exceptional story with global appeal. That’s the kind of writing I seek to translate; must-read fiction that English speakers will only get to read if somebody first acts as filter: finding it, and putting it into our language.

Serendipity helps determine what I translate, but doesn’t completely explain why I translate. For me, translation is effortful diversion, focused play. It stretches the same mental muscle as doing cryptic crosswords (the addictive, perverse, senselessly, time-wasting British puzzles—where, for example, the clue is: “She eats carrots, he said;” and the answer is “Mesopotamia.”) The linguistic gymnastics you perform in your head, decoding the clues, produce an outsize sense of exhilaration and reward, even if you land wrong on the first couple run-throughs. I’ve found similar satisfaction in studying foreign languages, though that process has more to do with routine than artistry. I started learning French at 10; German at 12; Russian at 17; Italian at 19, Spanish a decade later; and have always translated in the course of my work (fact checking and writing).

It wasn’t until I was in my 30s and got a call from the literature-in-translation website Words Without Borders that I began translating fiction. After publishing four stories for them (two from the Italian, two from the German), I was hooked. Since I caught the translation bug, I’ve lost my zeal for cryptic crosswords. I can’t bear to squander wordplay energy on a game, when I could channel it into translating literature into English.

This year, I’m translating a classic French novel into English. I like the discipline of translation; it’s like doing finger exercises on the piano, it strengthens technique, keeps you limber. But this week, I’m not translating, I’m just waiting; waiting to find out how readers react to Every Day, Every Hour in English, to see if the story of Luka and Dora’s thwarted love affair retains its power in English. When I think of the book, I remember it in its German incarnation, because that’s how its characters, story and dialogues were inscribed on my memory. A translation is not a clone of the original creation; it’s a blood descendant, with shared genes, but with its own distinct DNA. If a translation and its original, personified, were to stand side-by-side before a mirror, they would show similar, but not identical, faces. I hope that my translation makes Nataša Dragnić’s characters live and breathe for the English-speaking audience; and that first-time readers feel as strong a connection with Luka and Dora in English as I did when I was introduced to them a year and half ago, auf Deutsch.

27 May 2012 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.