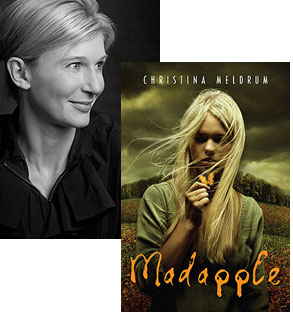

Christina Meldrum: Getting Fiction’s Facts Right

Christina Meldrum’s Madapple is packaged as a young adult novel, but I suspect that’s true in the same sense that Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief. (That both novels were published by Knopf’s young readers division may or may not be a coincidence.) In this essay, Meldrum talks about how she strove to make her fiction reflect the real world at a time when nonfiction chases after the dramatic allure of fiction.

Recently the melding of fiction and nonfiction has ignited controversy. James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces and Margaret Jones’s Love and Consequences were both criticized for fictionalizing events in what was presented to the public as a memoir: While Frey conceded that his core story of addiction recovery was enahnced by dramatic embellishments, Jones (real name: Margaret Seltzer) delivered an account of a half-Native American girl who grew up in a foster home and was a gang member in South Central Los Angeles when, according to Seltzer’s sister, she is white, grew up with her biological parents, and was never a member of a gang. The general consensus of readers seemed to be that memoir should be based in truth; if the story is fictionalized, it is not memoir.

But what about fiction that is based in non-fiction? Does the author of a novel have an obligation to his or her reader to make certain all non-fiction references are factually accurate? Much less consensus seems to exist on this point. Edward P. Jones wrote an account of black slave owners in The Known World; as a reader, I assumed the novel was based in research. I assumed the historical references to census data were based on actual census data, and that when Jones claimed that eight of thirty-four freed slave families in his “Manchester County” owned slaves, the figure was representative of what may well have happened historically. But these assumptions were wrong. When I finished reading The Known World and read the interview with Edward P. Jones that followed the story, I was stunned and frustrated to learn he had “made up” the census data. I felt cheated.

20 August 2008 | guest authors |

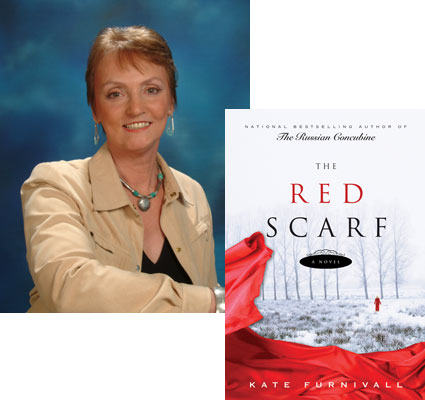

Kate Furnivall on the Road to Moscow

Authors turn to historical fiction for a variety of reasons—for Kate Furnivall, whose second novel, The Red Scarf, comes out this month, it’s all about coming to terms with the surprising revelations of her own family history, and understanding a cultural legacy that she didn’t even know about for most of her life.

Writing is therapy. There’s no question about it. Scratch any author and she or he will tell you it’s true. Writing The Russian Concubine and The Red Scarf helped me to accept who I am.

I was in my forties when I discovered I was part Russian, that my grandmother had been a White Russian in St Petersburg. It came as a shock. Her name was Valentina and she fled from the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution in 1917, down into China with her three-year-old daughter—my mother. Well, you could have knocked me down with a babushka.

So how do you deal with a discovery like that? When you learn you are not after all the pure English rose you’d always thought you were? It felt as if someone had pulled the rug out from under my feet and replaced it with a polovik. I had to rethink myself. But first I had to find out what being Russian meant. I had a preconceived notion, of course. Russia meant images of scary tanks strutting their stuff in Red Square, presidents who get drunk and topple over in public, and red-cheeked dolls that swallow each other like the whale and Jonah. Yes, I’d read my share of Tolstoy and Chekhov in years gone by, cried over “Lara’s Theme,” and even waded through Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archilpelago in the 1970s. But I was aware that the depth of my ignorance was greater than a Siberian oil well.

7 July 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.