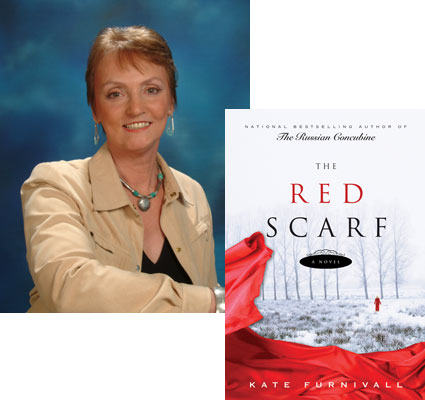

Kate Furnivall on the Road to Moscow

Authors turn to historical fiction for a variety of reasons—for Kate Furnivall, whose second novel, The Red Scarf, comes out this month, it’s all about coming to terms with the surprising revelations of her own family history, and understanding a cultural legacy that she didn’t even know about for most of her life.

Writing is therapy. There’s no question about it. Scratch any author and she or he will tell you it’s true. Writing The Russian Concubine and The Red Scarf helped me to accept who I am.

I was in my forties when I discovered I was part Russian, that my grandmother had been a White Russian in St Petersburg. It came as a shock. Her name was Valentina and she fled from the Bolsheviks after the Russian Revolution in 1917, down into China with her three-year-old daughter—my mother. Well, you could have knocked me down with a babushka.

So how do you deal with a discovery like that? When you learn you are not after all the pure English rose you’d always thought you were? It felt as if someone had pulled the rug out from under my feet and replaced it with a polovik. I had to rethink myself. But first I had to find out what being Russian meant. I had a preconceived notion, of course. Russia meant images of scary tanks strutting their stuff in Red Square, presidents who get drunk and topple over in public, and red-cheeked dolls that swallow each other like the whale and Jonah. Yes, I’d read my share of Tolstoy and Chekhov in years gone by, cried over “Lara’s Theme,” and even waded through Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archilpelago in the 1970s. But I was aware that the depth of my ignorance was greater than a Siberian oil well.

So what did I do? What do most people do when they feel no longer in control? I started to glean facts. I read anything and everything I could lay my hands on about Russia, then in the year 2000 two Big Things happened: my mother died and I finally fell totally in love with Russia. In an odd sort of way I felt I had now inherited her story—and that I mustn’t waste it.

That’s how The Russian Concubine and The Red Scarf came to be written. I wanted to bring together my emotions for my mother and for the grandmother I never knew and to celebrate the Russianness of my ancestry. Like anyone who is newly in love, I wanted to shout about it. To write about Russia and to show people what a breathtaking country it is. Literally, it takes my breath away. Its history, its culture, its politics, its geography, above all its people, and now… its future.

The Russian Concubine was the start. Though set in 1928 China in a fictional city called Junchow—which was really Tientsin (now Tianjin), where my mother was brought up—the opening chapter is in the snow-bound heart of Russia. And it is this chapter that provides the motivation and the turbulent events that drive the rest of the book. One of the characters is a great Cossack bear of a man who for me came to represent the intractable independent spirit of Russia.

But now I found myself on a rollercoaster, a gruelling ride, but exciting. And I didn’t want to get off. Not yet. I wanted more peaks, more lows, addicted to my passion for Russia. So The Red Scarf was born, a story set entirely in Russia, immersed in its culture and its communism of 1933, exploring how the powerful bonds of love, friendship and belief shape people’s lives.

The therapy is working. I have a clearer sense now of who I am. Where I came from. I am happy to have a colourful polovik under my feet and kolbasa on my table. I have travelled by road from Minsk to Moscow, from Novgorod to Petersburg, and seen for myself the enthralling Winter Palace, the astonishing summer palace at Peterhof and the primitive wooden villages in between. I can read their beautiful Cyrillic alphabet, even if I don’t understand what it says. All these experiences inform my writing and my comprehension of what I’m doing.

But am I ready to move on? No, I think not. Not yet. I am at the moment writing the sequel to The Russian Concubine and still leap out of bed each morning to rush to my desk and head straight for Moscow. At some deep level I need this, to merge myself and my Russian ancestry into one strong united whole, and one of the joys of it has been that a Russian publisher has bought The Russian Concubine. It will be translated into Russian. My writing came out of Russia and now, turning full circle, it is going back there. Going home.

(author photo by Max Danby)

7 July 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.