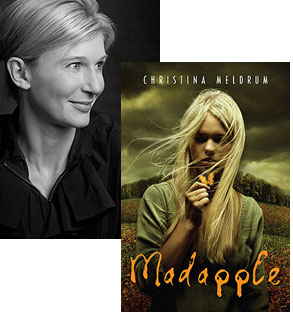

Christina Meldrum: Getting Fiction’s Facts Right

Christina Meldrum’s Madapple is packaged as a young adult novel, but I suspect that’s true in the same sense that Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief. (That both novels were published by Knopf’s young readers division may or may not be a coincidence.) In this essay, Meldrum talks about how she strove to make her fiction reflect the real world at a time when nonfiction chases after the dramatic allure of fiction.

Recently the melding of fiction and nonfiction has ignited controversy. James Frey’s A Million Little Pieces and Margaret Jones’s Love and Consequences were both criticized for fictionalizing events in what was presented to the public as a memoir: While Frey conceded that his core story of addiction recovery was enahnced by dramatic embellishments, Jones (real name: Margaret Seltzer) delivered an account of a half-Native American girl who grew up in a foster home and was a gang member in South Central Los Angeles when, according to Seltzer’s sister, she is white, grew up with her biological parents, and was never a member of a gang. The general consensus of readers seemed to be that memoir should be based in truth; if the story is fictionalized, it is not memoir.

But what about fiction that is based in non-fiction? Does the author of a novel have an obligation to his or her reader to make certain all non-fiction references are factually accurate? Much less consensus seems to exist on this point. Edward P. Jones wrote an account of black slave owners in The Known World; as a reader, I assumed the novel was based in research. I assumed the historical references to census data were based on actual census data, and that when Jones claimed that eight of thirty-four freed slave families in his “Manchester County” owned slaves, the figure was representative of what may well have happened historically. But these assumptions were wrong. When I finished reading The Known World and read the interview with Edward P. Jones that followed the story, I was stunned and frustrated to learn he had “made up” the census data. I felt cheated.

When reading Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, I did not make the same mistake and assume all his references were factually sound. Yet I did wonder which (if any) references were based in fact and which were not. And I wished Brown, as the author, had given me, as the reader, some insight into when he had taken literary license, and we he had not.

Personally, I love feeling enriched by a book, both emotionally and intellectually. I love when a novel both entertains me and teaches me. I love when I learn something surprising while reading a novel that fosters my seeing the world around me in a new way. For this reason, I seek out books like Andrea Barrett’s Servants of the Map and Ship Fever—books that are rich in factual references to science and nature and historical figures.

Now, I have written my own novel, one which incorporates a great deal of non-fiction. I was determined to make the references in Madapple as factually accurate as possible. I spent more than a year researching botany, and I consulted with a professor at Bowdoin College to insure my botanical references would be sound. I am an attorney by training, but I also consulted with a former criminal prosecutor to make certain my legal references would be realistic. The most challenging portion of my research and writing, though, had to do with my incorporation of religion and mythology.

Unlike the botanical and legal references, many of the descriptions of religion and mythology in Madapple are filtered through the perspective of the characters, meaning they are based in opinion—that is, the characters’ opinions, not mine. I do not mean to suggest the references to religion and mythology are not based in research. In addition to having studied comparative religion in college and having consulted with an expert from Stanford, Patrick Hunt, I did a great deal of independent research for Madapple regarding Norse mythology, early Christianity, Greco-Roman mythology, etc. But the theories regarding religion and mythology espoused by my characters are just that: theories. I included a bibliography at the end of Madapple to provide readers an opportunity to further pursue any of the characters’ theories, if they so choose. For me, this was the best way to balance fiction, non-fiction and literary license.

My hope for Madapple is that it will be the type of book I would have loved to read: a book that can both entertain and enrich and maybe—just maybe—spur readers to see the world around them in fresh way.

20 August 2008 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.