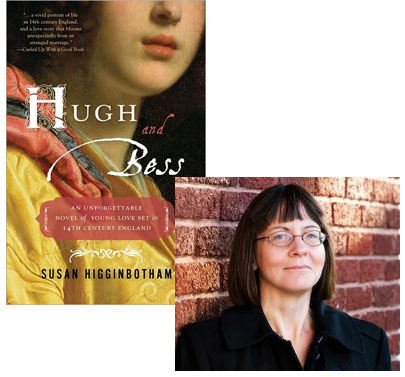

Susan Higginbotham: Discovering a Story in Edward II’s Court

I’m a sucker for historical fiction, so when I heard that Susan Higginbotham was making the rounds on the book-lovin’ Internet, introducing readers to her second novel, Hugh and Bess, my curiosity was piqued—not least of all because, based on what I’d gleaned from my preliminary readings, she’d dialed back the “epic” approach of her first novel, taking up a secondary character from that book and looking at him through a more intimate perspective. What, I wondered, led Higginbotham to that story? She was happy to explain.

When I first encountered Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II in graduate school, my professor told us, “Every English schoolboy knows how Edward II died.” Not being English or a schoolboy, I hadn’t heard of this king before; in fact, I would have been hard pressed to name any English kings before the Henrys in Shakespeare’s history plays. I most certainly couldn’t sort them out by Roman numeral. I read the play, and like my classmates duly shuddered when poor Edward meets his dreadful (and probably apocryphal) end. Then I forgot about him.

Over fifteen years, several moves, and two children later, I was surfing the Internet one night and came across an online version of the Marlowe play. I began reading a scene here and a scene there, and soon I simply gave in and re-read the whole play from start to finish. For some inexplicable reason, what I had found merely an interesting story back in the 1980’s had become a fascinating one to me now. I don’t know why, but I like to think it was simply because I was smarter in the 2000’s than I was in the 1980’s. Maybe it was because I no longer had those 1980’s shoulder pads wearing me down.

In any case, I am one of those people who feel compelled to read everything I can on a subject in which I become interested. (There’s probably something in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders about this; I’m better off not checking.) My quest for reading about all things Edward II soon took me to the local university library, and that’s where I discovered the tragic Despenser family, the most famous of whom were the father-and-son favorites of Edward II. From the thirteenth-century Hugh le Despenser, who fell in battle at Evesham beside Simon de Montfort, to the fifteenth-century Richard le Despenser, who died at age 18, each Despenser heir had died violently, young, or both.

My interest in the Despenser family had coincided with my newfound interest in fiction writing. As I began looking for information about the family, I discovered Eleanor de Clare, wife to Hugh le Despenser the younger and niece to Edward II. Her story, which took her on several revolutions of Fortune’s Wheel, begged to be told, and it turned into my first published novel, The Traitor’s Wife. (Along the way, I finally got all of my King Henrys and King Edwards straight. I still have trouble with the Georges.)

8 August 2009 | guest authors |

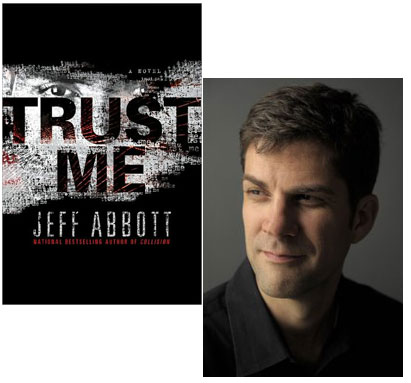

Jeff Abbott: A New Kind of Profiler

I’ve been on the Internet for 17 years now, so I know from experience—there’s a lot of disturbed people online. Today they write resentment-filled blogs, leave hateful comments on other people’s posts, or pick fights with each other on discussion forums, but I can remember when they used to hang out on Usenet newsgroups, ready to remind you over and over again of their moral and intellectual superiority to the rest of humanity. (Hell, I can remember too many occasions when I confused being a deliberately hurtful asshole with speaking truth to power.) For the most part, though, the Internet’s anklebiters, from the failed litterateurs to the most rabid political guttersnipers, are harmless; they’ll try to cut you down, and do their best to make you feel as small and impotent as they do—they congratulate themselves when they can get you to actually respond to their garbage—but unless you’re dealing with a real nutcase, they aren’t going to reach out and try to mess with your life.

But what if they did? What if, instead of expending all his energy ranting online about how this nation has sunk into degeneracy, one of these guys took the next step and started living the revolution instead of just basking in the aura? Jeff Abbott’s new novel, Trust Me, explores that scenario—how would these guys get driven to the tipping point, and what could we do to stop it? Heck, how would we see it coming?

My original thought in writing Trust Me was to write about a young man whose life had been derailed by a random act of violence, and who desperately wanted an answer to the unanswerable: why do people commit evil acts?

Ever since The Silence of the Lambs, audiences love to parse the psychology of evil. Popular culture has been full of criminal profilers: those practitioners who can look at a crime scene and deduce much of the killer’s mental makeup.

But I didn’t want to tread on well-worn ground. I wondered, where are the profilers of extremists? Someone with an extreme ideology and a bomb or a homegrown chemical lab can kill more people than a knife-wielding serial killer. How do we find and stop the next Timothy McVeigh, or the next Unabomber, or the next anthrax mailer? How do we find the next young American who decides to go to Somalia and fight for extremist groups—and perhaps return with a heart filled with hate? How do we find ways to make suicide bombing more unappealing to those who feel they have grievances against the world that can only be resolved through mass murder?

Luke Dantry, the hero of Trust Me, I decided, would be a first in suspense fiction: a profiler of extremists—a psychology graduate student trying to find those moving from angry words to murderous action. He would map their development psychologically, all with an eye to stopping them before they turned to violence. This would be his way of getting an answer to his question.

But how do you map a mind bending toward extremism?

30 July 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.