Jeff Abbott: A New Kind of Profiler

I’ve been on the Internet for 17 years now, so I know from experience—there’s a lot of disturbed people online. Today they write resentment-filled blogs, leave hateful comments on other people’s posts, or pick fights with each other on discussion forums, but I can remember when they used to hang out on Usenet newsgroups, ready to remind you over and over again of their moral and intellectual superiority to the rest of humanity. (Hell, I can remember too many occasions when I confused being a deliberately hurtful asshole with speaking truth to power.) For the most part, though, the Internet’s anklebiters, from the failed litterateurs to the most rabid political guttersnipers, are harmless; they’ll try to cut you down, and do their best to make you feel as small and impotent as they do—they congratulate themselves when they can get you to actually respond to their garbage—but unless you’re dealing with a real nutcase, they aren’t going to reach out and try to mess with your life.

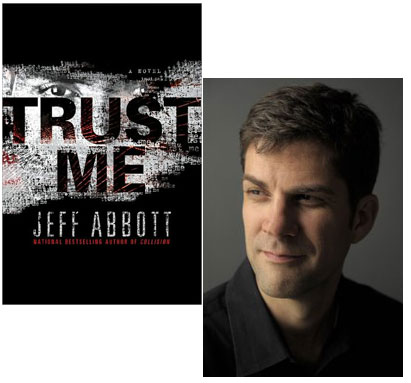

But what if they did? What if, instead of expending all his energy ranting online about how this nation has sunk into degeneracy, one of these guys took the next step and started living the revolution instead of just basking in the aura? Jeff Abbott’s new novel, Trust Me, explores that scenario—how would these guys get driven to the tipping point, and what could we do to stop it? Heck, how would we see it coming?

My original thought in writing Trust Me was to write about a young man whose life had been derailed by a random act of violence, and who desperately wanted an answer to the unanswerable: why do people commit evil acts?

Ever since The Silence of the Lambs, audiences love to parse the psychology of evil. Popular culture has been full of criminal profilers: those practitioners who can look at a crime scene and deduce much of the killer’s mental makeup.

But I didn’t want to tread on well-worn ground. I wondered, where are the profilers of extremists? Someone with an extreme ideology and a bomb or a homegrown chemical lab can kill more people than a knife-wielding serial killer. How do we find and stop the next Timothy McVeigh, or the next Unabomber, or the next anthrax mailer? How do we find the next young American who decides to go to Somalia and fight for extremist groups—and perhaps return with a heart filled with hate? How do we find ways to make suicide bombing more unappealing to those who feel they have grievances against the world that can only be resolved through mass murder?

Luke Dantry, the hero of Trust Me, I decided, would be a first in suspense fiction: a profiler of extremists—a psychology graduate student trying to find those moving from angry words to murderous action. He would map their development psychologically, all with an eye to stopping them before they turned to violence. This would be his way of getting an answer to his question.

But how do you map a mind bending toward extremism?

Timothy McVeigh wandered the country for three years, talking face-to-face with other extremists, hardening his positions, and finally parking his rented truck in front of the Murrah building. It can take months for a group like Hamas to identify, recruit, and indoctrinate a person, turning them from angry teenager to suicide bomber. There are a series of steps that extremists go through in moving from expressing verbal outrage to taking gun in hand or wiring a bomb. Stopping terrorism in the future could revolve around identifying and disrupting those psychological stages.

Extremism is social. The pressure to turn to violence often comes from other people. This once required a steady diet of meetings. Now, much of the recruitment and training takes place on the Internet. The University of Arizona has been tracking extremist web sites, forums, blogs, social networking sites, and videos. The numbers are staggering: fifty thousand extremist web sites, tens of thousands of instructional and propaganda videos, terrorism forums with thirty thousand members. (Some forums also offer recipe exchanges, movie reviews, and dating services.)

It’s nearly impossible to close these sites. Hamas has their own version of YouTube, called AqsaTube, loaded with homemade videos to recruit and train in firearms and bomb making. The FBI shut it down; it is now running on a rogue server in Russia. Other sites are taken down and reappear, like the heads of the Hydra. Hamas has even built their own film studio, to sell DVDs on the web and create more extremist content.

The making of a bomb is simply a technique. If Hamas posts a video on making a bomb, a eco-terrorist in New Zealand can blow up a corporate headquarters, a drug lord in Colombia can level a judge’s house, a criminal gang in Los Angeles can blast a rival’s den—all using the same technique described in the video.

What these sites are creating is a global library of violence, available to all.

These sites gave my hero Luke a back door into the extremist world. Penetrating widely divergent forums by pretending to be a believer in their various causes, he measures responses to comments, watches to see which members are shifting toward violence, tries to discover how to reduce the appeal of extremist messages. He gathers thousands of names and online identities. He believes that he’s safe on the other side of the computer screen. When he is kidnapped in a airport garage, he realizes that the people he has targeted have discovered and targeted him.

The spine of terrorism will never be broken until we figure out how to make extremism much less appealing. Extremist profilers like Luke Dantry are the frontline soldiers in that fight. Does Luke get an answer to his question? I think it’s safe to say he does but not the one he expects. In trying to find out why people do evil, he will discover every reason to do good.

30 July 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.