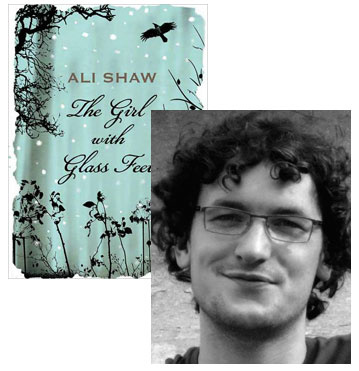

Ali Shaw and the Real-Life Glass Delusion

My airplane reading this week has been Ali Shaw’s debut novel, The Girl With Glass Feet, which is a contemporary fantasy written with such elegance that the literary crowd is already setting it aside for the “magic realism” camp. All kidding aside, it’s a wonderful story that ought to be embraced by fans of, let’s say, Charles de Lint and Aimee Bender alike, already up for Britain’s Costa Award (formerly the Whitbread) in the first novel category and sure to get plenty more recognition now that it’s finally out here in the States. In this essay, Shaw reveals how there’s actually a historical parallel to the curious condition of the woman at the center of his tale—but he never knew about it until after he’d finished writing.

Of all the bizarre notions and ideas that befuddled the heads of the medieval kings and queens of Europe, among the strangest must be the French king Charles VI’s conviction that his body was made from glass. This delusion saw the monarch dressing up in padded clothing, terrified to move for fear of smashing a limb, and it would be easy to dismiss as the unchecked imagination of a pampered royal were it not for the fact that Charles’s case was by no means unique. He was but the most high-profile sufferer of what would be retrospectively termed the glass delusion, a mental illness that could strike people down regardless of rank or social standing.

I came across the delusion not long after the UK publication of my novel about a girl who is turning, slowly but surely, into glass. Having spent a few years writing the book, trying all that time to imagine as vividly as possible what it might feel like for her, it was peculiar to discover that the victims of the glass delusion had been through something similar (in their minds at least) some five hundred years before. There are, of course, some obvious differences. Ida, the character in my book, really is turning into glass, whereas the sufferers of the glass delusion only thought that they were. And from what we can tell about those with the delusion, they didn’t think that their flesh and bones were transforming into glass but that their bodies had mysteriously transformed into fragile vessels: glass pitchers, beakers and flasks. These ‘glass men’ were diagnosed as melancholy, which back then was a far more severe assessment than that word would imply today. As melancholics, they were lumped together with those suffering from other fantastical delusions. Robert Burton listed some of them in 1621:

“Another thinks he is a nightingale, and therefore sings all the night long; another he is all glass, a pitcher, and will therefore let nobody come near him … one among the rest of a baker in Ferrara, that thought he was composed of butter, and durst not sit in the sun or come near the fire for fear of being melted.” (The Anatomy of Melancholy)

6 January 2010 | guest authors |

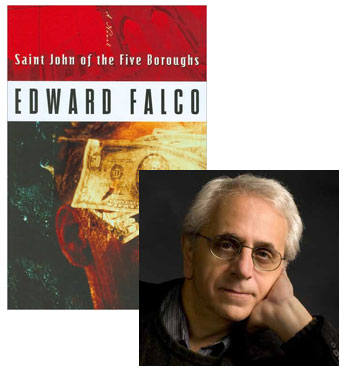

Ed Falco on Work That Works for Writers

One of the reasons I’m grateful for the existence of Unbridled Books is that it was this independent publishing company that introduced me to the writing of Ed Falco, starting with the short stories in Sabbath Night in the Church of the Piranha and up to his most recent novel, Saint John of the Five Boroughs. Back in November, Ed (and his niece, Edie Falco) did an illuminating interview with PopMatters: “We’re a working class family,” Ed said, “and to have two of us in the arts, and Edie succeeding as famously as she has, and I’m doing OK in my career, it’s nice, it’s fun.” This essay touches upon that point in a roundabout fashion, as Ed looks back at how he worked his way through to finding a job that truly supported his literary pursuits.

As the director of the creative writing program at Virginia Tech, I was recently in an administrative staff meeting convened to review the metrics by which the university measures our department’s performance; and while somebody was talking about something or other, I found myself looking around the room and wondering how I wound up there.

Throughout my twenties I imagined myself as a writer and a poet living on the fringes of mainstream culture. Okay, yes, I had a middle-class family who would always take me in when things got too bad, but, still, I spent most of my twenties going back and forth between working as a laborer and being unemployed, a period of time that included a year traveling throughout Europe and a three- or four-year stint working on horse farms and racetracks. I never made much money, I never had much money, and that was fine with me. I wanted to be a writer. I cared about art and injustice, and I believed that art could address injustice and make a difference. Over time my beliefs have shifted (shifted, not changed), but they haven’t shifted so far that I’ve come to sincerely care about departmental performance metrics. So how did I wind up there? When I asked a friend, a colleague of twenty-five years, he said: “You got old.”

27 December 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.