Ed Falco on Work That Works for Writers

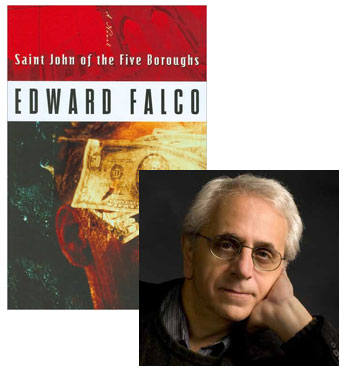

One of the reasons I’m grateful for the existence of Unbridled Books is that it was this independent publishing company that introduced me to the writing of Ed Falco, starting with the short stories in Sabbath Night in the Church of the Piranha and up to his most recent novel, Saint John of the Five Boroughs. Back in November, Ed (and his niece, Edie Falco) did an illuminating interview with PopMatters: “We’re a working class family,” Ed said, “and to have two of us in the arts, and Edie succeeding as famously as she has, and I’m doing OK in my career, it’s nice, it’s fun.” This essay touches upon that point in a roundabout fashion, as Ed looks back at how he worked his way through to finding a job that truly supported his literary pursuits.

As the director of the creative writing program at Virginia Tech, I was recently in an administrative staff meeting convened to review the metrics by which the university measures our department’s performance; and while somebody was talking about something or other, I found myself looking around the room and wondering how I wound up there.

Throughout my twenties I imagined myself as a writer and a poet living on the fringes of mainstream culture. Okay, yes, I had a middle-class family who would always take me in when things got too bad, but, still, I spent most of my twenties going back and forth between working as a laborer and being unemployed, a period of time that included a year traveling throughout Europe and a three- or four-year stint working on horse farms and racetracks. I never made much money, I never had much money, and that was fine with me. I wanted to be a writer. I cared about art and injustice, and I believed that art could address injustice and make a difference. Over time my beliefs have shifted (shifted, not changed), but they haven’t shifted so far that I’ve come to sincerely care about departmental performance metrics. So how did I wind up there? When I asked a friend, a colleague of twenty-five years, he said: “You got old.”

Well, not really. I mean, yes, I’m certainly not young anymore, but I think the answer has more to do with pursuing a life as a writer than it has to do with growing old. In fact, writers have always had to struggle with conflicts between the demands of making a living and the requirements of making art. As a young man, I took W.H. Auden’s advice to heart: In The Dyer’s Hand, he advises writers not pursue a career, like scholarship or journalism, that might draw on the same resources a writer needs to husband for his or her art, the point being that it’s not a good idea to spend all day writing articles or essays if you hope to come home and write a great poem or story. Auden’s advice shaped much of my youth, and it wasn’t until I was in my late twenties that I rejected it.

At that point I was pursuing a brief and disastrous career training standard bred racehorses. I spent my days with friends and co-workers who read nothing at all beyond the sports pages of the local newspapers (if that), before I went home, often exhausted, to spend a few hours reading and writing. Time was an issue and it was becoming more of an issue as the demands of the job expanded, but more than time or job demands, the bigger problem was, for me at least, that my daily life was not feeding my life as a writer. There’s something more than slightly schizophrenic in caring deeply about literature and art while spending all your waking hours with people for whom those things do not really exist.

I was unhappy—and so I moved on. I left racehorses behind and went back to school, to Syracuse University, where I got a Master’s degree, which I used upon graduation to pick up adjunct teaching positions, and I’ve been working in universities ever since. The great thing about university work is that I’m surrounded by writers and people who care about writing. The other great thing about it is that I can make my own schedule. For all of my years in teaching, I have always arranged my classes so that I have a few hours in the morning to write. That’s perfect for me. I write slowly anyway, one or two pages at a time, at most. I like to sleep on what I’ve written, to think about it overnight before going back to it the next day. Once I’ve put in my time writing, I spend the rest of the day taking care of life’s numerous demands, some of which are deeply fulfilling, the demands of family life and friendship, for example, and some of which are not so fulfilling, like thinking about departmental performance metrics.

Truth is, a successful career as a writer requires figuring out the best or at least most workable balance between daily life and the need for that quiet, meditative space where the best writing emerges. This is true for the great majority of writers who would starve if they had to live off their earnings, and for the few that earn a good income from their work. It was true for Wallace Stevens, who somehow wrote great poems while working as vice president of Hartford Insurance, and for William Carlos Williams, who managed a busy career as a doctor while almost simultaneously writing; and I’m sure it’s also true for someone like Dave Eggers, who has to balance his writing life with his life as a celebrity. For all of us, finding and maintaining a workable balance is a necessary element of the writer’s life.

27 December 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.