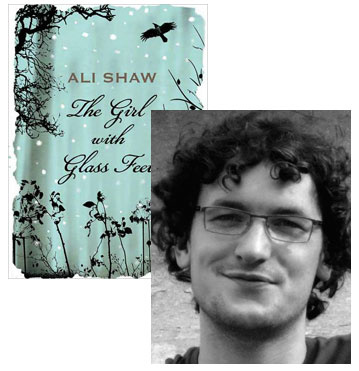

Ali Shaw and the Real-Life Glass Delusion

My airplane reading this week has been Ali Shaw’s debut novel, The Girl With Glass Feet, which is a contemporary fantasy written with such elegance that the literary crowd is already setting it aside for the “magic realism” camp. All kidding aside, it’s a wonderful story that ought to be embraced by fans of, let’s say, Charles de Lint and Aimee Bender alike, already up for Britain’s Costa Award (formerly the Whitbread) in the first novel category and sure to get plenty more recognition now that it’s finally out here in the States. In this essay, Shaw reveals how there’s actually a historical parallel to the curious condition of the woman at the center of his tale—but he never knew about it until after he’d finished writing.

Of all the bizarre notions and ideas that befuddled the heads of the medieval kings and queens of Europe, among the strangest must be the French king Charles VI’s conviction that his body was made from glass. This delusion saw the monarch dressing up in padded clothing, terrified to move for fear of smashing a limb, and it would be easy to dismiss as the unchecked imagination of a pampered royal were it not for the fact that Charles’s case was by no means unique. He was but the most high-profile sufferer of what would be retrospectively termed the glass delusion, a mental illness that could strike people down regardless of rank or social standing.

I came across the delusion not long after the UK publication of my novel about a girl who is turning, slowly but surely, into glass. Having spent a few years writing the book, trying all that time to imagine as vividly as possible what it might feel like for her, it was peculiar to discover that the victims of the glass delusion had been through something similar (in their minds at least) some five hundred years before. There are, of course, some obvious differences. Ida, the character in my book, really is turning into glass, whereas the sufferers of the glass delusion only thought that they were. And from what we can tell about those with the delusion, they didn’t think that their flesh and bones were transforming into glass but that their bodies had mysteriously transformed into fragile vessels: glass pitchers, beakers and flasks. These ‘glass men’ were diagnosed as melancholy, which back then was a far more severe assessment than that word would imply today. As melancholics, they were lumped together with those suffering from other fantastical delusions. Robert Burton listed some of them in 1621:

“Another thinks he is a nightingale, and therefore sings all the night long; another he is all glass, a pitcher, and will therefore let nobody come near him … one among the rest of a baker in Ferrara, that thought he was composed of butter, and durst not sit in the sun or come near the fire for fear of being melted.” (The Anatomy of Melancholy)

I must confess to a slight feeling of relief on discovering the differences between the delusion and the condition afflicting Ida in my novel. I generally feel opposed to the adage that truth is stranger than fiction, seeing it only as a call to arms to fiction-makers to try harder. Yet while I found that the glass delusion differed in its manifestation, I couldn’t help but notice a thematic similarity to what I was getting at in the novel.

Gill Speak has written a phenomenally informative essay on the delusion, in which she points out that it’s important to remember that, in the middle ages, humanity was not only convinced that the human soul existed but that it was a physical thing that dwelled in the body. To put it another way, the soul was the genie in the bottle. Glass men, who thought their bodies were beakers and bottles, simply had an overbearing sense of their own mortality, of how easily their body could smash. In a time when life expectancy was substantially poorer than it is today, it’s not surprising that people developed such deep-seated paranoia about their own fragility.

Therein lies the similarity to the novel. These days we don’t tend to think we’re made of glass, butter or candle wax, but we can be so wary of getting hurt by others that we don the emotional equivalent of Charles VI’s shatter-proof safety suit. Most of the characters in The Girl with Glass Feet have surrounded themselves with this kind of psychological padding, so much so that they’ve made certain they are barely living at all. It’s up to Ida to convince them to live their lives differently.

(Shaw adds, “If you’re interested in the glass delusion, I strongly recommend reading Gill Speak’s essay, “An odd kind of melancholy: reflections on the glass delusion in Europe (1440-1680),” in History of Psychiatry, Vol. 1, No. 2.”)

6 January 2010 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.