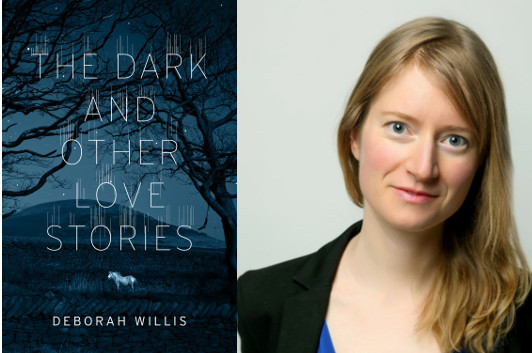

Deborah Willis: Misfits, Reapers, & Gothic

photo: Memotime Photograpy

I love the weird moments in The Dark and Other Love Stories, the short story collection by Deborah Willis. The lonely guy who winds up letting the crow that flies into his apartment stay, the little boy in an Optimus Prime outfit whose father forces him to egg an empty house on Halloween, the famous writer who tries to visit his grandmother’s old apartment in St. Petersburg after midnight. I’ve often said good fiction is about authentic responses to unusual situations, and Willis clearly gets that on a deep emotional level. And, as she discusses in this essay, the prompts that drive those responses can be very subtle…

When I wrote the title story from The Dark and Other Love Stories, I had recently read Flannery O’Connor’s Collected Stories. It took me several months to read every work of short fiction she wrote (because I’m a slow reader and because I think stories should be read carefully), so I had been living inside O’Connor’s mind for a while when “The Dark” poured out of me.

What a glorious feeling, when the writing is so fluid and easy—it’s a gift that comes so rarely. I sat in the coffee shop near my house, typing furiously. I now think that I can thank O’Connor for that gift. From reading her work, I had absorbed how to infuse an ordinary, seemingly innocuous scene with a sense of threat.

In “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” O’Connor begins with a light touch of humor as a family prepares for a road trip. The grandmother doesn’t want to go to Florida and tries to talk her son out of it by pointing to a newspaper article about The Misfit, a criminal who is “loose from the Federal Pen and headed towards Florida.” But the grandmother is an old lady who also worries that if she leaves her cat at home alone “he might brush against one of the gas burners and accidentally asphyxiate himself.” In her blue straw hat with a bunch of white violets on the brim, she is the picture of a silly biddy. We, as readers, don’t take her warning seriously.

10 March 2017 | selling shorts |

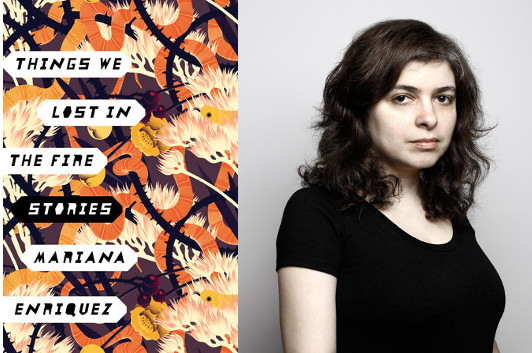

Mariana Enriquez: Robert Aickman’s Beautiful Uncertainty

photo: Nora Lezano

As you read the stories in Mariana Enriquez’s Things We Lost in the Fire, you’ll start to feel an unnerving sensation at the back of your mind, sometimes poking its way to the surface. Stories like “The Dirty Kid” or “The Intoxicated Years” aren’t horror; they aren’t even particularly supernatural. But they’ll unsettle you just the same. They’re… eerie. I understand that feeling a bit more now that I’ve read this guest post, where Enriquez talks about reading anthologies with writers like Shirley Jackson and Harlan Ellison…and another author I’d not heard of before, but whose stories sound intriguing enough that I want to track him down now.

Short stories weren’t my first love: When I started to write, the novel was my undertaking. I had to make my way to the short story and I managed that after fifteen years of writing. Argentinean literature is famous for its stories: its most important writer, Jorge Luis Borges, never wrote a novel and in fact never wrote a text that was too long; even his essays are short. Much of the canon—Julio Cortázar, Silvina Ocampo, Leopoldo Lugones, Horacio Quiroga, and, more recently, Abelardo Castillo, Hebe Uhart, and Fogwill—are above all short story writers, even if they occasionally dabbled into the novel. When I began, I didn’t want to go against tradition: one writes what one can. But the most natural movement for an Argentinean writer is towards the short story because that’s what he or she has read the most. Of course there are many novelists too, it’s just that the quantity and quality of short story writers is surprising for a national literature.

Nevertheless, if I have to choose a story or a writer who has influenced me, my favorite is not an Argentinean. He’s British: Robert Aickman. Reading him impressed me to commotion. I came across him in those cheap horror story anthologies that were very popular in Spain and Latin America in the 1980s, anthologies that mixed Shirley Jackson with Harlan Ellison, Henry James, Arthur Machen and had titles that scared off classy readers like Great Super Terror Vol. 1. The influence of an author who writes in a language different from your own is strange: the influence or the admiration reaches a place that is less technical and more intuitive. I suspect that the language of my stories is directly related to the tradition in my tongue. But the author who shook me to the core is Aickman.

He’s a superb creator of atmospheres. I read his stories many times to try to understand how he does it and I could list some of his decisions, but that would be unfair. Aickman eases one of my vexations with the conventional story. Particularly in genre stories, I was irritated more and more by the closed endings, the reassuring explanations. Closure: It doesn’t exist in life, I didn’t see why it had to exist in fiction. And I also didn’t want to understand step by step all the stories I read. Do we really understand everything that happens? I’d say we barely understand anything at all.

10 March 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.