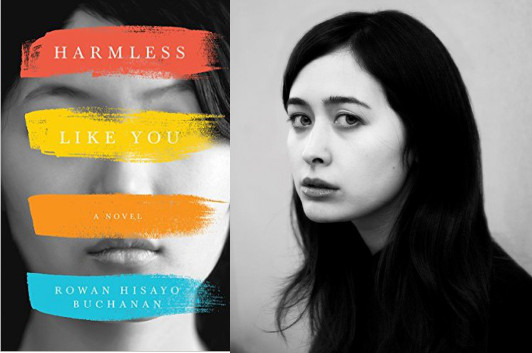

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s “NYC Novel”

photo: Eric Tortora Plato

It’s funny: I wouldn’t have thought of Rowan Hisayo Buchanan‘s Harmless Like You as a “New York novel,” exactly, even though, as she concedes in the essay below, a good part of the novel is set there, nearly half a century in the past. Part of my thinking is that it’s such a strongly character-driven novel, but that’s not to say there’s no strong sense of place, because Buchanan’s New York feels very authentic, even though it’s before my time as a New Yorker. Perhaps that’s because of how diligently Buchanan makes her characters, especially Yuki, pay attention to the world around them—the world becomes authentic through her eyes.

A few days ago, a friend called Harmless Like You a New York novel. The book is set in New York, Connecticut, and Berlin, but New York wins by page count. Still, I recoiled inside. I sipped my coffee and tried to keep a reasonable face. A New York novel. The phrase sounded smug as a young banker clinking his martini in a midtown bar. Could I have written such a thing? I just wanted to tell a story about a Japanese American woman who wants to be an artist and who leaves her son.

My first New York was a dream. I was born in London, a city almost as large, and just as written about. My dream New York didn’’t come from Audrey Hepburn standing outside Tiffany’s or the glossy I <3 NY sign. My New York was passed down to me by my mother. It was a home that she missed and I think, by telling stories, she rebuilt the city in our kitchen. It was the New York where she’d played with the Catholic kids and wandered into Mass by mistake. It was the New York where, as a little girl, she’d sat with Greta Garbo on a park bench. It was the New York where her mother left her in the Metropolitan Museum with museum guards for babysitters.

When I was eighteen, I moved to New York. I walked the Brooklyn Bridge eating lychees on a hot August night. I fought with a friend and sat out on his fire escape to sulk. Slowly, I stopped thinking of these scenes as New York moments. They just became moments. I had a grocery store, a bodega, a subway stop that I thought of as mine.

20 March 2017 | guest authors |

Read This: Five Came Back

(I originally wrote this review of Five Came Back when it came out in 2014, but the editor who assigned it to me didn’t know it had already been assigned to someone else. So I set it aside… But now that Netflix is about to unveil a documentary series based on the book, as well as showcasing several of the films Mark Harris talks about, I felt like, well, this was a pretty good review, maybe people should see it. So here we are.)

Every great movie director has a shadow filmography, the pictures that never got made, and there’s a brief passage in Five Came Back, Mark Harris’ group history of A-list Hollywood auteurs who applied their talents to the American military effort during the Second World War, that touches on a few projects pitched to studios in the late 1930s which were rejected for being out of step with the national mood before America was ready to fully commit itself to battle. John Ford saw Jean Renoir’s Grand Illusion and wanted to do an English-language remake; George Stevens hit upon the anti-war novel Paths of Glory two decades before Stanley Kubrick. Even a Frank Capra film about Valley Forge, with Gary Cooper playing George Washington, was turned down because the head of Columbia Studios “couldn’t bring himself to finance a movie in which audiences would be encouraged to root against British soldiers at a moment when England was under an even greater threat from Germany.”

Ford had already signed up with the Navy months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Capra joined the Army’s Signal Corps division soon after, as did William Wyler and John Huston; Stevens had to finish out a contract with Columbia, but enlisted in January 1943. As in his previous book, Pictures at an Exhibition, Harris has several timelines to work with here, and he effectively crosscuts between these five directors’ wartime experiences, creating a smooth narrative that even makes room to explore the larger dynamics of the awkward relationship between the wartime government in Washington and the Hollywood studios.

13 March 2017 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.