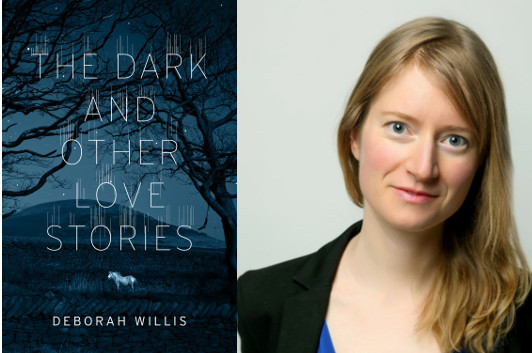

Deborah Willis: Misfits, Reapers, & Gothic

photo: Memotime Photograpy

I love the weird moments in The Dark and Other Love Stories, the short story collection by Deborah Willis. The lonely guy who winds up letting the crow that flies into his apartment stay, the little boy in an Optimus Prime outfit whose father forces him to egg an empty house on Halloween, the famous writer who tries to visit his grandmother’s old apartment in St. Petersburg after midnight. I’ve often said good fiction is about authentic responses to unusual situations, and Willis clearly gets that on a deep emotional level. And, as she discusses in this essay, the prompts that drive those responses can be very subtle…

When I wrote the title story from The Dark and Other Love Stories, I had recently read Flannery O’Connor’s Collected Stories. It took me several months to read every work of short fiction she wrote (because I’m a slow reader and because I think stories should be read carefully), so I had been living inside O’Connor’s mind for a while when “The Dark” poured out of me.

What a glorious feeling, when the writing is so fluid and easy—it’s a gift that comes so rarely. I sat in the coffee shop near my house, typing furiously. I now think that I can thank O’Connor for that gift. From reading her work, I had absorbed how to infuse an ordinary, seemingly innocuous scene with a sense of threat.

In “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” O’Connor begins with a light touch of humor as a family prepares for a road trip. The grandmother doesn’t want to go to Florida and tries to talk her son out of it by pointing to a newspaper article about The Misfit, a criminal who is “loose from the Federal Pen and headed towards Florida.” But the grandmother is an old lady who also worries that if she leaves her cat at home alone “he might brush against one of the gas burners and accidentally asphyxiate himself.” In her blue straw hat with a bunch of white violets on the brim, she is the picture of a silly biddy. We, as readers, don’t take her warning seriously.

But the warning about The Misfit is there nonetheless, in the first paragraph. We are distracted from it, we might smile at it, but still it has lodged itself in our minds—the possibility of danger. Alice Munro employs the same technique when opening “Save the Reaper,” a brilliant story that she acknowledges was directly influenced by “A Good Man Is Hard to Find”. In the first paragraph of Munro’s fiction, a grandmother is driving her grandchildren to get ice cream, and they are playing a make-believe game in the car. The game consists of pretending that the occupants of other cars are “newly arrived space travelers on their way to…the invaders’ lair.” The game insinuates that “[g]as station attendants or women pushing baby carriages or even the babies riding in the carriages” could be dangerous beings. As readers, we consciously understand that a grandmother is playing an innocent game with her grandson. But we unconsciously understand that threat is everywhere. “[A]nybody might be one.”

Speaking of conscious and unconscious, I can’t say that I consciously adopted this technique to infuse suspense into my story, “The Dark.” But I now see O’Connor and Munro’s fingerprints there, in the fact that my story opens with two girls in a canoe on what seems to be a placid lake. But there is something amiss—the girls are taking an unnecessary risk by paddling away from the group. I hope that the opening scene plants the idea of danger in the reader’s mind, and that it sticks there like a burr. I hope it shows the longing for freedom that will drive the girls to take other, more perilous chances.

“The Dark” is what I like to think of as “Summer Camp Gothic,” a genre I just invented right now and will henceforth define as involving a summer-camp setting (goes without saying), a close-knit community that is not entirely what it seems (what evil lurks behind the sing-alongs and soccer games?) and explores the tensions and pressures of coming of age.

I can’t claim to have mastered Summer Camp Gothic the way that O’Connor mastered rural Southern Gothic and Munro mastered Southern Ontario Gothic. I can only hope that I learned deeply from reading these two extraordinarily skilled writers. O’Connor and Munro are masters, I believe, because they know how to make readers feel what their characters feel—and by feel, I truly mean feel in our bodies. In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” and “Save the Reaper,” the grandmothers’ dread and shock and sorrow are ours too.

10 March 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.