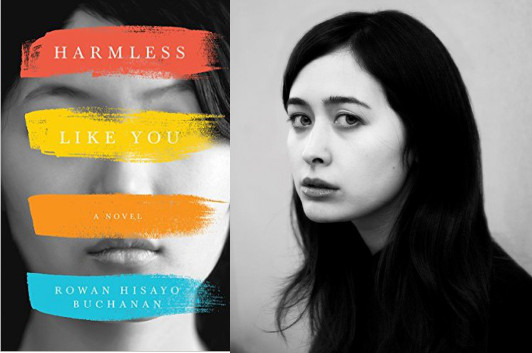

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s “NYC Novel”

photo: Eric Tortora Plato

It’s funny: I wouldn’t have thought of Rowan Hisayo Buchanan‘s Harmless Like You as a “New York novel,” exactly, even though, as she concedes in the essay below, a good part of the novel is set there, nearly half a century in the past. Part of my thinking is that it’s such a strongly character-driven novel, but that’s not to say there’s no strong sense of place, because Buchanan’s New York feels very authentic, even though it’s before my time as a New Yorker. Perhaps that’s because of how diligently Buchanan makes her characters, especially Yuki, pay attention to the world around them—the world becomes authentic through her eyes.

A few days ago, a friend called Harmless Like You a New York novel. The book is set in New York, Connecticut, and Berlin, but New York wins by page count. Still, I recoiled inside. I sipped my coffee and tried to keep a reasonable face. A New York novel. The phrase sounded smug as a young banker clinking his martini in a midtown bar. Could I have written such a thing? I just wanted to tell a story about a Japanese American woman who wants to be an artist and who leaves her son.

My first New York was a dream. I was born in London, a city almost as large, and just as written about. My dream New York didn’’t come from Audrey Hepburn standing outside Tiffany’s or the glossy I <3 NY sign. My New York was passed down to me by my mother. It was a home that she missed and I think, by telling stories, she rebuilt the city in our kitchen. It was the New York where she’d played with the Catholic kids and wandered into Mass by mistake. It was the New York where, as a little girl, she’d sat with Greta Garbo on a park bench. It was the New York where her mother left her in the Metropolitan Museum with museum guards for babysitters.

When I was eighteen, I moved to New York. I walked the Brooklyn Bridge eating lychees on a hot August night. I fought with a friend and sat out on his fire escape to sulk. Slowly, I stopped thinking of these scenes as New York moments. They just became moments. I had a grocery store, a bodega, a subway stop that I thought of as mine.

Then I left to attend graduate school in Wisconsin. For the first month, I claimed I could hear the silence of that state. Even when people were talking, I could hear the great beast of silence behind them. In the winter, the lake froze so hard that I could jump on it. The restaurants offered a dish called beer cheese soup. At night, I could see the needle-sharp stars, but I longed for the pink haze of a New York night. As I drafted the novel, I lived with my feet in Wisconsin and my head dreaming of New York.

Harmless Like You has two timelines—one in the present day and one running through the 1960s into the ’80s. People asked, why choose a city so written about, at a time so already beloved? When I was very young, I watched Breakfast at Tiffany’s. In it, Mickey Rooney puts on glasses and buck teeth to impersonate a Japanese landlord. He screams and bumps into things. My Japanese grandfather was a soft-spoken man with excellent English. The divide was so great that I had no idea who or what Mickey Rooney was trying to be. He just seemed loud. For a long time, Breakfast at Tiffany’s was the only piece of art of about the life of a Japanese person in New York that I knew. I wanted to tell a different story.

As I began the book, I imagined I was walking into the dream city that my mother had built for me. But I found as I wrote, like all dreams, its geography didn’t quite make sense. New York in the 1960s and 1970s was dangerous, and chaotic. Andy Warhol was shot. There was an oil slick around the Statue of Liberty. Arson was rife. The stories I’d grown up with were of a studious, well-loved girl. But, of course, studious well-loved girls are to be found in the most dangerous of times.

As she rode to school in the Bronx, she shared the commute with a flasher who displayed himself regularly. This New York had to appear alongside the sweetness. I called home to clarify the stories that I knew so well. I asked questions like, What exactly were you wearing in 1968? I pulled up old Vogue and Harpers Bazaar covers. I searched for street photography. I found a New York that wasn’t my mother’s and wasn’t my own. It was a New York that belonged to Yuki, my protagonist. What would she notice? What would drift past?

So maybe it’s true—I’ve written a New York novel. I wonder: What the city will make of it?

20 March 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.