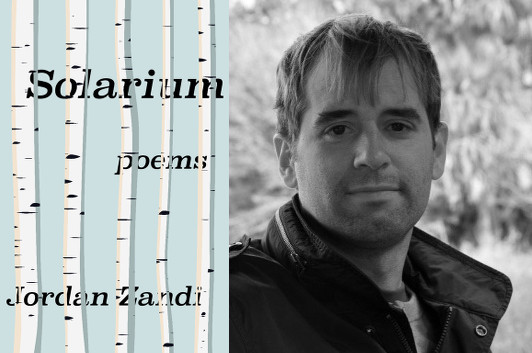

Jordan Zandi: Borrowing Szymborksa

photo courtesy Jordan Zandi

Jordan Zandi is the winner of the 2014 Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry, on the strength of his debut collection, Solarium. When you read a poem like “Chamber Music,” or the one that gives the collection its title, you’re in the presence of a poet who’s able to nimbly position himself within the natural world, but who’s also well aware of the theatricality of that positioning—and able to convey it to you without being overly arch about it, so that the voice seems as natural as the setting. In this guest essay, he talks about a poet whose work helps him get to that place.

My experience with process when it comes to poetry is that it works in cycles; and during the winter phase I write as badly as I ever have, as if I’ve learned nothing since first starting. My imagination becomes an old wooden hunk that I hack into forced chunks of language until a poem clatters onto the floor. The end.

Or so it feels. I once brought a longish one of these poems, roughly three pages, to my most trusted reader. She put a star beside one line and then told me that the rest was dead; throw it out. “Borrow this,” she said, “it’ll help you generate material,” and she handed me a collection by Wisława Szymborksa.

Like Wallace Stevens’, Szymborksa’s poems offer transport to a world. There are strange landscapes, vignettes, charming anecdotes, parables and fabulae, and scenarios arising out of untamed logics. When I’m writing badly, such transport is what I need. Look, for example, at this hilariousness in “In Heraclitus’s River:”

In Heraclitus’s river

a fish is busy fishing

a fish guts a fish with a sharp fish

a fish builds a fish, a fish lives in a fish,

a fish escapes from a fish under siege.So much work gets enmired in predictability: You read the first few lines and you can ballpark the rest; or you write a few lines and you realize you’re going straight where you’ve gone before. But you cannot guess where most of her poems will go, even in this one, where the root of the logic is so forthrightly acknowledged.

27 February 2016 | poets on poets |

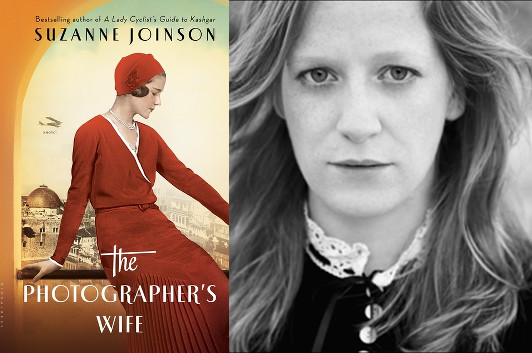

Suzanne Joinson’s Writing Takes Wing

photo: Simon Webb

I first met Suzanne Joinson back in 2012, when Bloomsbury held a reception to introduce her to book review editors and literary journalists shortly before the publication of her first novel, A Lady Cyclist’s Guide to Kashgar. When I found out recently that she had a new book, The Photographer’s Wife, coming out, I was eager to read it, and I’m happy to report that I’m currently riveted by the story of 11-year-old Prue, the daughter of an English architect who’s in charge of an ambitious development project in Jerusalem in the year 1920, and how she gets caught up in the intrigues of the adults around her—and, then, seventeen years later, back in England, some of those mysteries return to intrude upon her life in decidedly unwelcome ways. It’s still early stages for me, and I’m not quite sure how it’s going to turn out, but I’m looking forward to learning. Meanwhile, in this guest post, Joinson talks about what it took for her to be able to arrange her day-to-day reality in such a way that she could create this vivid world of imagination.

What must it feel like to be a wingwalker? Balancing on the wing of an aeroplane as it loops and swoops in the bright blue sky? The idea for The Photographer’s Wife came to me in the middle of a windy airfield at a vintage bi-plane show. The crowd went crazy when the brave wingwalkers appeared in their blue and yellow costumes, blazoned with their sponsor’s logo: UTTERLY BUTTERLY: I CAN’T BELIEVE IT’S NOT BUTTER! All young, glamorous women, they looked like cheerleaders from another era as they climbed into insane contraptions on the top of the aircrafts.

In the end there are no wingwalkers in my book, nor is there a reference to my day of standing in the airfield, but it was the beginning. Shortly after, I organised becoming a writer-in-residence at a 1930s art deco airport in Shoreham, England where I rummaged in the not-very-well-kept archives. I found secrets and letters and photographs of pilots who were given five hours flight training and then sent to far-off cities: Salonika (now Thessaloniki), Jerusalem, Cairo. A story grew in me, coming up from the bones of the land, about the place as well as the people, driven by my desire to understand its web of connections across the world.

11 February 2016 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.