Jordan Zandi: Borrowing Szymborksa

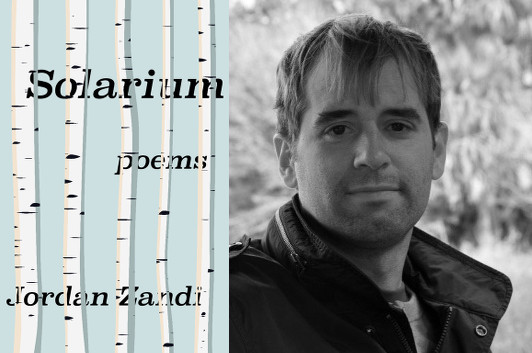

photo courtesy Jordan Zandi

Jordan Zandi is the winner of the 2014 Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry, on the strength of his debut collection, Solarium. When you read a poem like “Chamber Music,” or the one that gives the collection its title, you’re in the presence of a poet who’s able to nimbly position himself within the natural world, but who’s also well aware of the theatricality of that positioning—and able to convey it to you without being overly arch about it, so that the voice seems as natural as the setting. In this guest essay, he talks about a poet whose work helps him get to that place.

My experience with process when it comes to poetry is that it works in cycles; and during the winter phase I write as badly as I ever have, as if I’ve learned nothing since first starting. My imagination becomes an old wooden hunk that I hack into forced chunks of language until a poem clatters onto the floor. The end.

Or so it feels. I once brought a longish one of these poems, roughly three pages, to my most trusted reader. She put a star beside one line and then told me that the rest was dead; throw it out. “Borrow this,” she said, “it’ll help you generate material,” and she handed me a collection by Wisława Szymborksa.

Like Wallace Stevens’, Szymborksa’s poems offer transport to a world. There are strange landscapes, vignettes, charming anecdotes, parables and fabulae, and scenarios arising out of untamed logics. When I’m writing badly, such transport is what I need. Look, for example, at this hilariousness in “In Heraclitus’s River:”

In Heraclitus’s river

a fish is busy fishing

a fish guts a fish with a sharp fish

a fish builds a fish, a fish lives in a fish,

a fish escapes from a fish under siege.So much work gets enmired in predictability: You read the first few lines and you can ballpark the rest; or you write a few lines and you realize you’re going straight where you’ve gone before. But you cannot guess where most of her poems will go, even in this one, where the root of the logic is so forthrightly acknowledged.

Elsewhere Szymborska gives us the raw immediacy of a mind experiencing. “So these are the Himalayas,” she begins her “Notes from a Nonexistent Himalayan Expedition.” Not “Those are” or “Here are some Himalayas” or “Before us are Himalayas, reader,” but “So these are.” There’s an immediate depth conveyed here that I’d love to aspire to, as if whoever is speaking has a continuum of existence and experience, one communicated with the economy of three words. That is, they’ve been told of these mountains now before them, and they’re in the midst of this realization when we join in on the poem.

I also love Syzmborska’s sense of participation in her own work. In “Landscape” she has the cheekiness to tell the reader—with an irreverent familiarity—that she’s a painted woman in a painting done by a Master (“Why of course, my dear, / I am the woman there, under the ash tree”). We the addressed become acknowledged visitors to that landscape, and we step into a scene that extends beyond what we can see. “The trees,” we are told, “have roots beneath the oil paint.” Later, there is an entryway into a house “behind which life goes on unpainted.” As with the road to Emmaus tale, you realize the figure beside you is really the Master.

I find these microcosms endlessly convincing for their ability to suggest so much more than they make available. My wish isn’t to imitate; it’s to be reminded of how to experience illusion again as though stepping into the realness of dream. At the root of my problem there’s always doubt and fear. “It’s gone,” I tell myself. “I’ll never be convinced by what I’m writing again.” And if I’m not convinced, what reader would ever be? Finding and reading work like Szymborska’s is part of a process I have to go through over and over. However, when I’ve found the right writer for the right time and keep reading, eventually I sit down at my desk and find that there’s a new place waiting, one I can go to with a renewed sense of urgency.

27 February 2016 | poets on poets |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.