Suzanne Joinson’s Writing Takes Wing

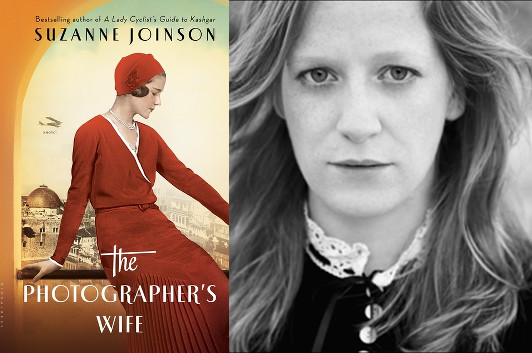

photo: Simon Webb

I first met Suzanne Joinson back in 2012, when Bloomsbury held a reception to introduce her to book review editors and literary journalists shortly before the publication of her first novel, A Lady Cyclist’s Guide to Kashgar. When I found out recently that she had a new book, The Photographer’s Wife, coming out, I was eager to read it, and I’m happy to report that I’m currently riveted by the story of 11-year-old Prue, the daughter of an English architect who’s in charge of an ambitious development project in Jerusalem in the year 1920, and how she gets caught up in the intrigues of the adults around her—and, then, seventeen years later, back in England, some of those mysteries return to intrude upon her life in decidedly unwelcome ways. It’s still early stages for me, and I’m not quite sure how it’s going to turn out, but I’m looking forward to learning. Meanwhile, in this guest post, Joinson talks about what it took for her to be able to arrange her day-to-day reality in such a way that she could create this vivid world of imagination.

What must it feel like to be a wingwalker? Balancing on the wing of an aeroplane as it loops and swoops in the bright blue sky? The idea for The Photographer’s Wife came to me in the middle of a windy airfield at a vintage bi-plane show. The crowd went crazy when the brave wingwalkers appeared in their blue and yellow costumes, blazoned with their sponsor’s logo: UTTERLY BUTTERLY: I CAN’T BELIEVE IT’S NOT BUTTER! All young, glamorous women, they looked like cheerleaders from another era as they climbed into insane contraptions on the top of the aircrafts.

In the end there are no wingwalkers in my book, nor is there a reference to my day of standing in the airfield, but it was the beginning. Shortly after, I organised becoming a writer-in-residence at a 1930s art deco airport in Shoreham, England where I rummaged in the not-very-well-kept archives. I found secrets and letters and photographs of pilots who were given five hours flight training and then sent to far-off cities: Salonika (now Thessaloniki), Jerusalem, Cairo. A story grew in me, coming up from the bones of the land, about the place as well as the people, driven by my desire to understand its web of connections across the world.

The cooking up of a novel is a long, weird process. It often starts years before pen is put to paper, or finger to keyboard, and if the white screen or page is looked at for long enough then a whole number of trapdoors begin triggering open in the recesses of the mind. Which way to go? Which connection to follow? During this writing phase I was invited abroad several times—for a conference or to write a travel piece or take part in a translation project—and on many of these journeys something went wrong. I was delayed in the Tel Aviv airport for eight hours. I was stuck in a provincial airport near the Yellow Mountains in China for hours. I was stranded in the Beijing airport. I spent extensive hours alone in eerie buildings with glass domed ceilings and huge toilets. I wouldn’t talk to another person for hours. I consumed odd combinations of pastries and chewing gum and noodles and juice.

In these zones, I wrote in a haphazard, unsystematic way, flicking between notebook and iPad, making drifting connections. I remembered my Irish grandmother (now aged 96) telling me about running across the Rossmore Estate in Monaghan to greet Amy Johnson as she landed her plane, agog at the marvel of her buck-teeth. I remembered how, as kids (in the 1980s, before cheap flights), we couldn’t afford to go abroad, but would go to Manchester airport to “watch the planes.” Day-trips of sandwiches and thermos flask, happy hours noting aircrafts taxi-ing in and out; waving at pilots who never saw us.

I got lost for a while, in the middle of my book, and also in the middle of my life. I had two kids under five and the chaos of trying to carve out a system to actually write (essentially selfish) and be a mother (essentially selfless) was overwhelming and there were times when I thought I couldn’t do it. Propelled by a nameless instinct, I figured out a method which helped: I would go to my nearest airport, Gatwick, London, and write in one of the generic chain restaurants in the departure lounge. Laptop plugged in, drinking tea all day, staff who didn’t care. There is an odd quality to being in an airport, a strange loss of the self that happens so that paralysing labels such as “Mother” or “Writer” or “Wife” or “Daughter” dissolve into the piped Justin Beiber and the light smell of grease coming over everything. A space opens up, and for that short time, writing can occur.

Stories seep through blood and matter and time. They take memories and photographs and feelings and knit and combine, swooping like the wingwalker, exhilarated in the wind, clamped into her safety contraption. In the nowhere place of airports I could read and work on my manuscript under a different light, literally—neon—and metaphorically. Perhaps it is a melancholy thing to do, to take yourself off to an airport and go nowhere, but writers are prone to melancholy, so I embraced it. And it worked. Airports and flying represent the paradox of escape: both running away and running home, which is the tidal undercurrent of The Photographer’s Wife. Through the course of writing it, after years of restless travel, I made a discovery. If I can sit with one foot ready to hop on a plane and the other foot half in my own front door, I achieve something I never thought I would find: equilibrium. A still-point between the two places I want to be and rather than being torn apart, I can simply be there.

It’s the closest I’ve come to peace, and I can only find it—temporarily—through the writing of a novel. Not the publishing or talking about or having a book cover for or blurbing or selling of a novel (although all of those things are extremely welcome), but through the writing of it. The secret, intimate moment that happens at a table in the corner of the vast empty café. The flight between this memory and that thought, which hopefully achieves, after much circling, a cohesive coming together. It takes years of balancing on wings to achieve it, but on those rare moments when I get there, it’s the closest I’ve ever come to flying.

11 February 2016 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.