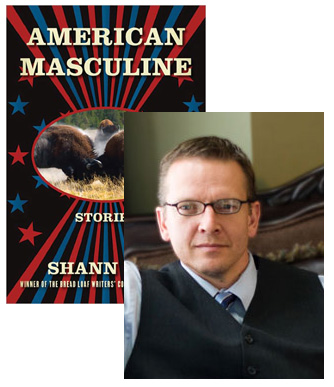

Shann Ray & the Phenomenology of Love

Shann Ray‘s short story collection, American Masculine, is the winner of this year’s Bakeless Prize, presented annually by the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference to support emerging writers. (Last year, I featured a poem by the previous winner, Nick Lantz.) These are some fantastic stories; Ray’s reflections on how we face the raw, brutal hurts life can throw us are never completely dispassionate, but a collection of stories entirely like “The Great Divide” would be hard to take, which is why I’m glad for the optimistic flashes in “How We Fall” or “When We Rise” (which is not to say these latter stories are especially cheery). In this guest essay, Ray tells us about another author who could convey with precise detail the effect of an intense emotion like love on the human spirit.

Some poets, for a time, are lost to us.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was lost to me, and it was only after some years I found her again in her Selected Poems, a book issued in the Library of Classic Poets series (Gramercy/Random House, 2001). Born in 1806 at Coxhoe Hall, Durham, England, she was the first of twelve children. By ten years old she had read passages from Paradise Lost and a number of Shakespearean plays, among other great works. By the age of twelve she had written her first “epic” poem, composed of four books of rhyming couplets. Yet by fourteen Elizabeth had developed a lung ailment that plagued her for the rest of her life. Doctors administered morphine, which she took until her death. At fifteen, she also suffered a spinal injury.

Despite her physical setbacks, her mind continued to bloom and she consistently sought to bring healing to others through her writing. During her teens she taught herself Hebrew in order to better read the Old Testament. Later she turned to Greek studies, and her appetite for the classics was matched by a passionate Christian faith. At age twenty Elizabeth anonymously published An Essay on Mind and Other Poems. At twenty-two her mother died, affecting her deeply. The ongoing abolition of slavery in England and financial misdirection cut into her father’s income, and in 1832, he sold his estate and moved the family to a coastal town, before settling permanently in London. While living on the coast, Elizabeth’s translation of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound(1833) was published.

As her work gained greater audience in the 1830s, Elizabeth stayed in her father’s London house under his tyrannical rule. He began sending her siblings to Jamaica to help with the family’s estates there. Elizabeth bitterly opposed slavery and did not want her brothers and sisters sent away. With her health waning she spent a year at the sea of Torquay accompanied by a favorite brother Edward, whom she called “Bro.” He drowned while sailing at Torquay and Elizabeth came home emotionally bankrupt. Her next five years were spent as an invalid and a recluse in her bedroom at her father’s home.

In the face of despair she continued writing, and in 1844 produced a collection entitled simply Poems. In one of the poems Elizabeth had praised the poet Robert Browning, and he wrote her a letter. Together over the next twenty months the two exchanged 574 letters. Their love was directly opposed by her father, a man who wanted none of his children to marry. In 1846, Robert and Elizabeth eloped and settled in Florence, Italy, where Elizabeth’s health improved and she bore a son, Robert Wideman Browning. Her father never spoke to her again.

27 June 2011 | guest authors |

Read This: Asimov to Austen

I’ve had a couple of recent appearances at other websites. This morning, I’m back in Shelf Awareness, talking about Paul Malmont’s The Astounding, The Amazing, and the Unknown, which starts from a historically true premise—Robert A. Heinlein recruited Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague de Camp to work with him in a research laboratory at the Philadelphia Navy Yard to help defeat the Axis—and works in L. Ron Hubbard’s (mis)adventures during the Second World War, legends surrounding the suppressed research of Nicola Tesla, and a few more surprise guest stars. As I point out in my review, the secret history Malmont lays out isn’t 100 percent accurate, but for the most part it is fun enough that you’re not going to want to sit around trying to poke holes in it anyway.

I’ve had a couple of recent appearances at other websites. This morning, I’m back in Shelf Awareness, talking about Paul Malmont’s The Astounding, The Amazing, and the Unknown, which starts from a historically true premise—Robert A. Heinlein recruited Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague de Camp to work with him in a research laboratory at the Philadelphia Navy Yard to help defeat the Axis—and works in L. Ron Hubbard’s (mis)adventures during the Second World War, legends surrounding the suppressed research of Nicola Tesla, and a few more surprise guest stars. As I point out in my review, the secret history Malmont lays out isn’t 100 percent accurate, but for the most part it is fun enough that you’re not going to want to sit around trying to poke holes in it anyway.

Before that, over at Heroes & Heartbreakers, I shared my thoughts on William Deresiewicz’s A Jane Austen Education, in which the English professor and literary critic reveals how his character was refined by the reading of Jane Austen’s six novels. Fortunately, it’s not Just about how Emma made him realize how self-absorbed he was; Deresiewicz really does love Austen’s stories for their own sake, and that love is probably the thing he’s most convncingly able to get across to readers. If you aren’t very familiar with Austen—which I’m still not, although I’m getting started—he’ll definitely give you a good idea what all the fuss is about.

Finally, inReads.com, the book-centric social networking site I’ve been advising, had its full public unveiling earlier this week, including the latest in the series of “Whatcha Reading?” videos I’ve been shooting. This time around, I spoke to Holly Black and Ellen Kushner after they’d finished a signing at Books of Wonder to celebrate the publication of Welcome to Bordertown, a new collection of stories set in the shared-world fantasy setting first explored in a set of Terri Windling-edited anthologies back in the mid-1980s.

24 June 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.