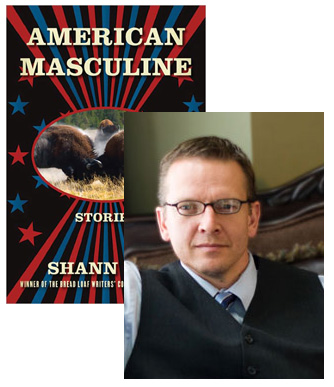

Shann Ray & the Phenomenology of Love

Shann Ray‘s short story collection, American Masculine, is the winner of this year’s Bakeless Prize, presented annually by the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference to support emerging writers. (Last year, I featured a poem by the previous winner, Nick Lantz.) These are some fantastic stories; Ray’s reflections on how we face the raw, brutal hurts life can throw us are never completely dispassionate, but a collection of stories entirely like “The Great Divide” would be hard to take, which is why I’m glad for the optimistic flashes in “How We Fall” or “When We Rise” (which is not to say these latter stories are especially cheery). In this guest essay, Ray tells us about another author who could convey with precise detail the effect of an intense emotion like love on the human spirit.

Some poets, for a time, are lost to us.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was lost to me, and it was only after some years I found her again in her Selected Poems, a book issued in the Library of Classic Poets series (Gramercy/Random House, 2001). Born in 1806 at Coxhoe Hall, Durham, England, she was the first of twelve children. By ten years old she had read passages from Paradise Lost and a number of Shakespearean plays, among other great works. By the age of twelve she had written her first “epic” poem, composed of four books of rhyming couplets. Yet by fourteen Elizabeth had developed a lung ailment that plagued her for the rest of her life. Doctors administered morphine, which she took until her death. At fifteen, she also suffered a spinal injury.

Despite her physical setbacks, her mind continued to bloom and she consistently sought to bring healing to others through her writing. During her teens she taught herself Hebrew in order to better read the Old Testament. Later she turned to Greek studies, and her appetite for the classics was matched by a passionate Christian faith. At age twenty Elizabeth anonymously published An Essay on Mind and Other Poems. At twenty-two her mother died, affecting her deeply. The ongoing abolition of slavery in England and financial misdirection cut into her father’s income, and in 1832, he sold his estate and moved the family to a coastal town, before settling permanently in London. While living on the coast, Elizabeth’s translation of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound(1833) was published.

As her work gained greater audience in the 1830s, Elizabeth stayed in her father’s London house under his tyrannical rule. He began sending her siblings to Jamaica to help with the family’s estates there. Elizabeth bitterly opposed slavery and did not want her brothers and sisters sent away. With her health waning she spent a year at the sea of Torquay accompanied by a favorite brother Edward, whom she called “Bro.” He drowned while sailing at Torquay and Elizabeth came home emotionally bankrupt. Her next five years were spent as an invalid and a recluse in her bedroom at her father’s home.

In the face of despair she continued writing, and in 1844 produced a collection entitled simply Poems. In one of the poems Elizabeth had praised the poet Robert Browning, and he wrote her a letter. Together over the next twenty months the two exchanged 574 letters. Their love was directly opposed by her father, a man who wanted none of his children to marry. In 1846, Robert and Elizabeth eloped and settled in Florence, Italy, where Elizabeth’s health improved and she bore a son, Robert Wideman Browning. Her father never spoke to her again.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, the woman whose work was favorably compared to Shakespeare and Petrarch, died in Florence at the age of fifty-seven on June 29, 1861. Despite her crushing physical ailments and the total rejection she experienced by her father, in the following poem, a poem touched with beauty and grace toward her husband Robert, she leads others into a healed expression of love itself. In so doing, she expands our ways of knowing:

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.Considering Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s devotion to language, to the nuances of people and connection and to the hope of discovering self and others and the world, her words carry significant power. “I love thee with the breath, smiles, tears, of all my life.” Her voice echoes a similar advance in mature relationships: let us move toward an understanding of one another that leads us to know one another, to love one another. Now, in the present, before it’s too late. For the person who is dominant, distant, or needy, and far from both a thoughtful understanding of the interior of the self or the interior of others, the lack of such love is a void in which darkness dwells, a desperate place, fragile and lonely. But for one who has discovered the elegant power of loving and being loved, the vessel of humanity is seemingly unconquerable.

Consider the following stanzas:

Love me Sweet, with all thou art

Feeling, thinking, seeing;

Love me in the lightest part,

Love me in full being.Love me with thy thinking soul,

Break it to love-sighing;

Love me with thy thoughts that roll

On through living—dying.Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poetry provides a fitting place for a conversation on the possibilities that exist in the paradox of love and power, which is also the paradox of justice and forgiveness. The tensions of human conflict can be likened to a light born of heaven and shown in the perpetual gifts of human goodness… but those same tensions can also be seen like a great fire reminding us of the hell we so often create by our relentless capacity for evil. In receiving the gift of life each person is confronted by forces undeniably mysterious, formidable, and unwieldy. If the nature of our daily encounter with existence could be captured in a directive, it might be precisely the one Elizabeth has given us:

Love me in full being.

Considering the lack of love that so often haunts us, her statement is of grave importance. Considering the ugly ways of her father, and her own lifelong physical struggles, her statement is a triumph.

Elizabeth continues her radiant declaration:

Through all hopes that keep us brave,

Farther off or nigher,

Love me for the house and grave,

And for something higher.In Elizabeth Barrett Browning we find the bright nucleus of what it means to love—to love the world, to love others more than our own lives—and from this essence emerges the joy of wholehearted devotion to what is essential in this life. With her we enter together the crucible of human existence, with its ever present capacity for good and evil, and emerge with a sense of refinement, wholeness, and holiness.

27 June 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.