Haikasoru: Translating Genre from Japan

Earlier this week, The World SF Blog paid tribute to Haikasoru, an imprint of VIZ Media focusing on English-language translations of Japanese science fiction and fantasy. Haikasoru’s editorial director, Nick Mamatas, contributed a post on some distinctive features of Japanese SF, both cultural and literary—especially the fact that, although “Japanese SF authors grew up reading US and UK SF and have fully embraced the idiom,” in these books “the future is Japanese,” and it can be very edifying for Western readers to be exposed to more non-Anglo, non-American visions of the future.

Earlier this week, The World SF Blog paid tribute to Haikasoru, an imprint of VIZ Media focusing on English-language translations of Japanese science fiction and fantasy. Haikasoru’s editorial director, Nick Mamatas, contributed a post on some distinctive features of Japanese SF, both cultural and literary—especially the fact that, although “Japanese SF authors grew up reading US and UK SF and have fully embraced the idiom,” in these books “the future is Japanese,” and it can be very edifying for Western readers to be exposed to more non-Anglo, non-American visions of the future.

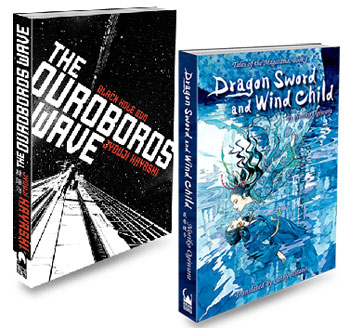

His post reminded me that I’d actually gotten in touch with the folks at Haikasoru a while back, with the idea of soliciting some guest essays from their translators for the recurring series here at Beatrice, and that Mamatas had kindly put together a bit of Q&A where he approached Jim Hubbert and Cathy Hirano and asked them about their work on novels like Jyouji Hayashi’s The Ouroboros Wave and Noriko Ogiwara’s Dragon Sword and Wind Child. I’ve been meaning to post this for a while, and I’m glad I finally pulled myself together and got it online, because there’s some really wonderful insights into translation in their answers to Mamatas’ questions. “The Japanese science fiction and fantasy we publish is meant to compete against the best English-language books on the shelves,” he wrote in his introduction to this piece. “For that I needed translators who had the instincts of novelists, and those are few and far between.” Based on these answers, and what I’ve read of the books, he’s found at least two winners.

What’s it like, being North Americans in Japan and working as translators?

Jim Hubbert: This is a bit hard to answer. Since I’ve spent most of my adult life in Tokyo, I’m not sure what it would be like to be a translator in North America! Japanese has been a central interest of mine since the mid-70s, and I can’t imagine being away from the environment where it’s spoken. I suppose I could be based somewhere else and translate, but without having the language coming at me every day, I’d worry that my instincts for meaning and nuance would suffer a bit. Japanese is a radically different vehicle of expression from my native English, and it still gets the drop on me regularly, which is part of the fascination.

Since I’m based in Japan, keeping my own idiolect current and evolving is something I try to work at. Through entertainment and the Internet I have no shortage of access to the English language—better access than I’d have to Japanese, were I outside of Japan—but I try to keep myself exposed to different voices. I don’t have a huge fiction library, but if I like something, I’ll go back to it every few years. Some nonfiction is amazing from a language standpoint, like Shelby Foote’s Civil War trilogy, which was my mental tuning fork for rendering some of the violence in The Lord of the Sands of Time.

I think of the time I spend reading fiction as another form of language study. Authors have their own distinct idiolects. Without diverse exposure to what can be done with English, I’d have a harder time finding the right tone when translating fiction.

25 March 2011 | in translation |

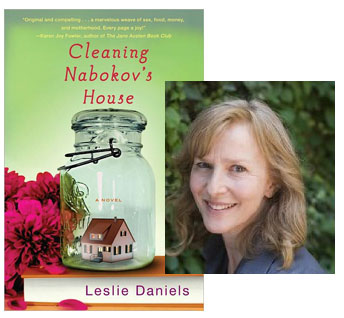

Leslie Daniels: Sitting Alone, Laughing, Writing

I hope you’ll forgive me a certain amount of prejudice when it comes to Cleaning Nabokov’s House—after all, the author is my own literary agent, Leslie Daniels, here making her full-length fiction debut. It’s a novel about a woman in crisis: Barb Barrett has walked out on her loveless marriage, which has led to her losing custody of her children—basically, as the novel opens she’s pretty much out of it and scrambling to find her way back in. The house she’s just moved into in upstate New York was once Vladimir Nabokov’s home, and she finds a manuscript crammed way in the back that might be one of his. (It’s a stack of index cards, for that extra bit of verisimilitude.)

Now, yes, Barb’s rediscovery of her self-confidence and capability does involve trying to get that manuscript authenticated and published, but that goal actually takes a backseat to a much more unusual revenue stream (the nature of which I won’t spoil for you)… it’s utterly implausible that Barb would get away with this plan, but the voice that Leslie gives Barb goes a long way towards making the story work. (Ultimately, I’d say you should be able to suspend your disbelief just as readily as you would for a quirky romantic comedy at the cinema.) I’ve known for a while that Leslie writes fiction in addition to representing other writers, but I didn’t know what drove her to write this novel… so I asked!

I started writing Cleaning Nabokov’s House in my father’s last year of life. As he was weakening and his language disappearing, I found I could reach him through food and with humor. At the end it was only humor. I wrote for solace then, and to witness the numbered days we had left. During that time I believed I was no longer capable of being happy, but I was funny. At some point in the writing I did while my dad was dying, the voice of the narrator started to emerge, the nothing left to lose, the humor, the grit.

Writing the book involved a lot of sitting alone in my house laughing till I cried and vice versa, but writing down the punch lines and then trying to justify them with narrative and plot. I wanted every single funny thing that came along. If you can be funny, you must, you should. It’s like beauty or the ability to make money, a calling.

Some writers start with a large idea, and I started only with writing, investigating my interests. I put into that early writing on the project all my coordinates: mourning, food, sexual passion, longing, reading genius writers, reading ordinary writers.

23 March 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.