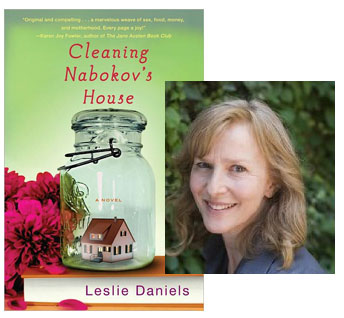

Leslie Daniels: Sitting Alone, Laughing, Writing

I hope you’ll forgive me a certain amount of prejudice when it comes to Cleaning Nabokov’s House—after all, the author is my own literary agent, Leslie Daniels, here making her full-length fiction debut. It’s a novel about a woman in crisis: Barb Barrett has walked out on her loveless marriage, which has led to her losing custody of her children—basically, as the novel opens she’s pretty much out of it and scrambling to find her way back in. The house she’s just moved into in upstate New York was once Vladimir Nabokov’s home, and she finds a manuscript crammed way in the back that might be one of his. (It’s a stack of index cards, for that extra bit of verisimilitude.)

Now, yes, Barb’s rediscovery of her self-confidence and capability does involve trying to get that manuscript authenticated and published, but that goal actually takes a backseat to a much more unusual revenue stream (the nature of which I won’t spoil for you)… it’s utterly implausible that Barb would get away with this plan, but the voice that Leslie gives Barb goes a long way towards making the story work. (Ultimately, I’d say you should be able to suspend your disbelief just as readily as you would for a quirky romantic comedy at the cinema.) I’ve known for a while that Leslie writes fiction in addition to representing other writers, but I didn’t know what drove her to write this novel… so I asked!

I started writing Cleaning Nabokov’s House in my father’s last year of life. As he was weakening and his language disappearing, I found I could reach him through food and with humor. At the end it was only humor. I wrote for solace then, and to witness the numbered days we had left. During that time I believed I was no longer capable of being happy, but I was funny. At some point in the writing I did while my dad was dying, the voice of the narrator started to emerge, the nothing left to lose, the humor, the grit.

Writing the book involved a lot of sitting alone in my house laughing till I cried and vice versa, but writing down the punch lines and then trying to justify them with narrative and plot. I wanted every single funny thing that came along. If you can be funny, you must, you should. It’s like beauty or the ability to make money, a calling.

Some writers start with a large idea, and I started only with writing, investigating my interests. I put into that early writing on the project all my coordinates: mourning, food, sexual passion, longing, reading genius writers, reading ordinary writers.

The book started as a map of the middle of a life. We all have known the feeling of being at the edge of our world. It is akin to the feeling of being lost. For me the book and the central character, Barb Barrett came out of that moment of questioning: Where am I? What did I do to get myself here? How do I find my way onward? I conceived of the book as a shout out, like a nighttime flare from a fallen airplane: Over here!

The plot may have started in my writing a fan letter to a real local dairy, Hillcrest of Moravia, New York, commending them on their excellent butter. I worked hard on that letter. They never answered me, which I attributed to them being too busy milking cows and churning. I invented a character whose job it was to answer the mail at a dairy. She narrates the book.

One sentence of that early investigative writing gave me a road map that I then had to follow. It came before the plot, but it was compelling and it led me forward.

Writing can be very subversive. I had great fun ridiculing certain dull conventions and oppressive aspects of life. I recommend that. It is also entirely solitary. There was something bizarre about sitting alone in my own house wearing sweat pants or the basic house rags, writing desperately, urgently, sometimes crying at the sad things I had just invented, sometimes laughing at my own jokes, sometimes both. I often felt like there was an orangutan in my head rattling the bars, making rude noises. It was very peculiar. I kept thinking that this can’t possibly be the way to write a novel. And you have no guidelines as to whether it is good or not. I went from feeling aligned with Samuel Beckett to feeling like a horse’s ass. But both of those feelings seemed true at the time.

After the years I have spent as a literary agent, fiction editor for a literary magazine, and teaching writing, I think about writers and their work in a very personal way. As a reader I am democratic, I will read anything that interests me whether it is “high” as in literary fiction, or “low” as in commercial fiction. But I am an exacting reader. When I read commercial fiction, I often want it to aim higher: to be more surprising, fresh, original. Concordantly, when reading literary fiction I often want it to aim lower: be better paced, more engaging, less obfuscating. I had the idea of writing something that had deep respect for language but would draw in the reader. I think I tried to write the book I wanted to read next.

23 March 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.