Read This: Old-Timey Science Fantasy

I have two new book reviews running today: My latest Shelf Awareness piece is a look at Stephen Hunt’s The Rise of the Iron Moon, and I make my debut at Heroes and Heartbreakers, the new romance site from the folks who brought you Tor.com, discussing M.K. Hobson’s The Native Star, one of this year’s nominees for the Best Novel Nebula. (I’ll be posting about some of the other nominees over the next week or so, too.)

I have two new book reviews running today: My latest Shelf Awareness piece is a look at Stephen Hunt’s The Rise of the Iron Moon, and I make my debut at Heroes and Heartbreakers, the new romance site from the folks who brought you Tor.com, discussing M.K. Hobson’s The Native Star, one of this year’s nominees for the Best Novel Nebula. (I’ll be posting about some of the other nominees over the next week or so, too.)

I’ve had my eye on Stephen Hunt’s novels for a while, and the opportunity to review this book gave me a chance to reach back to The Court of the Air and The Kingdom Beyond the Sea—like The Rise of the Iron Moon, they’re set in a semi-steampunky world dominated by the Kingdom of Jackals, which feels to me a bit like England if the Parliament had never been re-usurped by the Stuart Restoration. (So the Jeckelian royal family really is just for show, and not in a particularly pleasant way; in Court, it’s established early on that the monarch’s arms are cut off when he or she ascends to the throne, literalizing the dictum that the king shall never again raise arms against the nation.) There’s a lot I came to like about this series, although I did mention in my review that “readers expecting finely tuned realism may find Hunt’s stylistic fidelity to his 19th-century inspirations cartoonish,” and in fact it took me a fair amount of time to get used to that voice—even now, I confess I’m not really all that enamored of, say, the broguish sea captain who appears in all the stories. And there’s no getting around the fact that all three of these stories are about orphans on heroic quests with the fate of the world (or at least the Kingdom of Jackals) at stake; it’s a perfectly entertaining archetypal narrative, sure, but I’d be interested in seeing Hunt take another approach to the fictional world he’s created.

The Native Star is an alternate history fantasy, set in an 1870s America where magic works (and has worked for centures), but it’s also a straight-up romance novel running on a classic “opposites attract” engine: Take a headstrong country witch and a smug big-city warlock, thrust them into a life-threatening situation which requires them to work together, and watch the sparks fly. It works very effectively as a historical romance, with the distinction that the story is told only from the heroine’s perspective. (Many historicals tend to give equal weight to the hero and the heroine, letting readers into their thoughts as they struggle to overcome whatever emotional or psychological blocks are keeping them from being in a fully engaged and loving relationship with each other.) The danger is thwarted in such a way as to leave room for a sequel, even beyond the “Happily Ever After” point at which romances traditionally end, a trait which The Native Star shares with Gail Carriger’s wonderful debut novel, Soulless. “If Hobson is as effective at deepening the layers of her imagined world as Carriger has proven to be,” I observed, “it will be interesting to see where she takes her couple after their whirlwind (and refreshingly chaste) courtship.” In the meantime, I’m impressed at how the Science Fiction Writers of America, the organization that selects candidates for the Nebulas, has embraced a book that can’t be contained by a single genre. (Maybe that’s not surprising, though: Just a few years ago, they gave the prize to Michael Chabon’s alternate history private eye novel, The Yiddish Policemen’s Union.)

22 March 2011 | read this |

Victoria Patterson & the Continuous Dialogue Between Writers

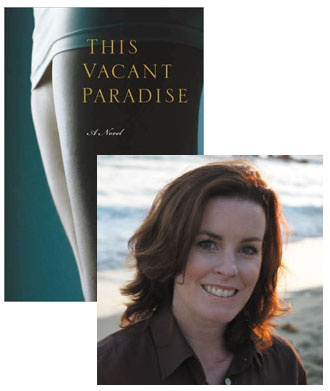

I was introduced to Victoria Patterson‘s fiction last year, when her short story collection, Drift, was a finalist for The Story Prize, and she was kind enough to write an essay about Frederick Busch for this website. When I heard about her debut novel, This Vacant Paradise, and learned that it started out as a bid at remolding Edith Wharton for contemporary southern California, I was intrigued—and I’m delighted that Victoria was willing to talk about the ways in which great fiction can stay with us and influence the stories we want to tell. I’m looking forward to cracking this novel open this afternoon, and I think after you learn more about it, you’ll want to track it down, too.

As writers, we do tend to talk to each other through our work. John Updike said, “I have almost always begun a book with another book in mind…” Through what he called such “intertextuality,” Updike felt, “writers give each other the courage to carry on.”

More recently, Yiyun Li said of William Trevor, “I talk to him in my stories.” Some of her stories, in fact, are direct responses to Trevor’s stories, reminiscent of Raymond Carver saying he was writing to and for Anton Chekhov.

“It just feels like he’s writing about my own world,” Li explained of Trevor, “or how I feel about the world is the way he feels about the world, and I write about the world the way he does.” Li thanks Trevor in her acknowledgments, and in almost every interview, she mentions him.

While on the surface their worlds are seemingly far apart (Li’s work takes place mostly in China, while Trevor’s work takes place mostly in Ireland), their exacting, careful prose is similar—with a deep sense of loneliness, an underlying melancholy and seriousness, and an understated beauty. Li has conversations with other writers, including arguments—Graham Greene and Iris Murdoch, for instance—but she’s in alignment with Trevor, with whom her connection is deeper. She describes this connection as “intuitive.” Surely, her relationship to Trevor’s work is intimate, and although they’ve met a few times, these interactions “don’t matter…because really it’s the things you write, because you’re talking to a writer, and you really talk through your writing.”

18 March 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.