Thaisa Frank’s Second Look at First Novels (& One Other)

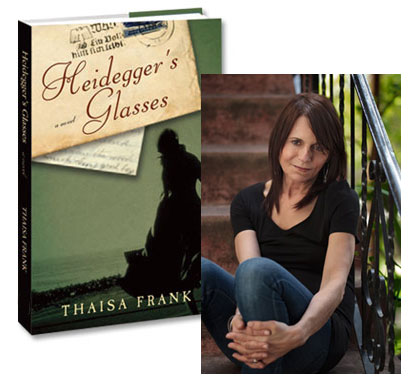

The Third Reich had a program, called Briefaktion (“Operation Mail”), in which arrivals at concentration camps such as Auschwitz were compelled to write letters and postcards praising conditions and assuring their families that all was well. From this historical truth, Thaisa Frank has imagined a shadow program, called the “Compound of Scribes,” tasked with answering those letters after they’ve been returned as undeliverable—usually because their intended recipients would have already been deported by the time the mail arrived. “Himmler… believed in the supernatural with a vengeance,” Frank writes in her debut novel Heidegger’s Glasses, “and thought the dead would pester psychics for answers if they knew their letters were destroyed—ultimately exposing the Final Solution.” As the Reich begins to collapse under the sustained onslaught of the Allied forces, the letter-writers at the compound are given a new task: Martin Heidegger wrote a letter to his optometrist, but doesn’t know that he’s already been sent to the camps and executed, so they must write a letter that would convince Heidegger, who has been corresponding about philosophy with his friend for years. So, as you can imagine, “voice” is a crucial element of Frank’s writing—which she discussed when I interviewed her back in 1997—and she shares with us some other novels in which voice plays an especially substantial role.

There are a plethora of successful second novels that undoubtedly have been given as gifts this holiday season, including A Curable Romantic by Joseph Skibell and C by Tom McCarthy. Like Freedom and Great House, these are excellent gifts for readers who like dense, well-written books—and so are Skibell and McCarthy’s first novels.

Although each tells a very different story, both of their first novels are told by first-person narrators with a distinctive voice that creates the character and informs the plot. And both grew visible through serendipity: Skibell’s A Blessing on the Moon became a best seller as a result of recommendations by independent bookstores; McCarthy’s Remainder couldn’t find a publisher in England and was published in France, where it became a cult hit of the Paris underground.

7 January 2011 | guest authors |

It Became Necessary to Destroy Huckleberry Finn in Order to Save It

Our literary 2011 got off to a contentious start with the news that NewSouth is about to publish an edition of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn with a certain racial slur expunged from its vocabulary; instead, Huck and the adults around him will consistently refer to Jim as a “slave.” (It also includes a version of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer with “Indian” instead of “Injun,” but that’s not where all the attention is going.) Auburn professor Alan Gribben explained to the New York Times that he felt awkward having to say a certain word in front of students, and he didn’t think they much liked it either; as he writes in the introduction to his bowdlerized edition, “Even at the level of college and graduate school, students are capable of resenting textual encounters with this racial appellative.” Getting rid of that word, he insists, is the only way he can put the book in front of students to make them appreciate Twain’s incisive social critique.

Well, very few people apart from Prof. Gribben and his publisher seem to think this was a good idea. Perhaps Ice-T says it best:

As Ishmael Reed observed in The Wall Street Journal, “Twain used the words with which he was surrounded and to insist that he omit words is not only to put a gag on his characters but a gag on the Age.” Tayari Jones, in an op-ed piece for AOL News, echoed Reed’s point about Twain’s deliberate reflection of a painful and historical reality, adding: “The solution is not to fight willful ignorance with willful misrepresentation.” They’re both right: It’s one thing if the brutality of race relations in the United States in the years before the Civil War makes Alan Gribben uncomfortable—it’s another thing to create a deliberately false version of that society so he and like-minded educators can feel good about themselves. Gribben and NewSouth have not only done American literature a disservice, they have failed the students in any educational institution shallow enough to buy into their debased product.

6 January 2011 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.