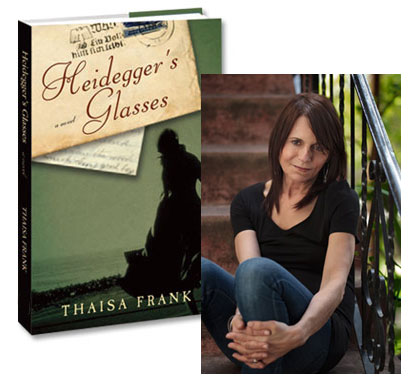

Thaisa Frank’s Second Look at First Novels (& One Other)

The Third Reich had a program, called Briefaktion (“Operation Mail”), in which arrivals at concentration camps such as Auschwitz were compelled to write letters and postcards praising conditions and assuring their families that all was well. From this historical truth, Thaisa Frank has imagined a shadow program, called the “Compound of Scribes,” tasked with answering those letters after they’ve been returned as undeliverable—usually because their intended recipients would have already been deported by the time the mail arrived. “Himmler… believed in the supernatural with a vengeance,” Frank writes in her debut novel Heidegger’s Glasses, “and thought the dead would pester psychics for answers if they knew their letters were destroyed—ultimately exposing the Final Solution.” As the Reich begins to collapse under the sustained onslaught of the Allied forces, the letter-writers at the compound are given a new task: Martin Heidegger wrote a letter to his optometrist, but doesn’t know that he’s already been sent to the camps and executed, so they must write a letter that would convince Heidegger, who has been corresponding about philosophy with his friend for years. So, as you can imagine, “voice” is a crucial element of Frank’s writing—which she discussed when I interviewed her back in 1997—and she shares with us some other novels in which voice plays an especially substantial role.

There are a plethora of successful second novels that undoubtedly have been given as gifts this holiday season, including A Curable Romantic by Joseph Skibell and C by Tom McCarthy. Like Freedom and Great House, these are excellent gifts for readers who like dense, well-written books—and so are Skibell and McCarthy’s first novels.

Although each tells a very different story, both of their first novels are told by first-person narrators with a distinctive voice that creates the character and informs the plot. And both grew visible through serendipity: Skibell’s A Blessing on the Moon became a best seller as a result of recommendations by independent bookstores; McCarthy’s Remainder couldn’t find a publisher in England and was published in France, where it became a cult hit of the Paris underground.

A Blessing on the Moon is written in the joyously ghoulish voice of a ghost whose family and friends have been murdered in the holocaust. Without comprehending what has happened he climbs out of a mass grave and runs to his old house, which is now occupied by a gentile family. With the inexorable logic of a fairy tale, the narrator is visible to their youngest daughter, whom he befriends, and confers with his rabbi, who has become a raven. The narrator is no longer alive but still involved with the world—and this is conveyed by the awe and agitation in his voice. This dissonance in voice drives the plot and there is a surprising resolution. A Blessing on the Moon never degenerates into easy magic realism but sustains the fantastic quality of a Chagall painting.

Remainder is narrated by a character who remembers nothing of his life before an accident that gave him amnesia. His pervasive sense of alienation never wavers, even after a settlement of 8.5 million pounds. But when he notices a crack in the wallpaper of a friend’s house, he sees an image of an apartment building, complete with occupants. He doesn’t know whether he’s actually seen the building; but the force of this neo-Proustian moment drives him to recreate the apartment, audition actors to be occupants and embark on a life of re-enactments. Like A Blessing on the Moon, the first-person voice contains immediate dissonance—in this case between an unacknowledged longing to remember and not seeming to care about forgetting. And, like A Blessing on the Moon, the tensions in the voice drive the plot.

For those readers compelled by a voice so powerful it can create immediate narrative tension, I would also recommend The Dwarf, by the Swedish Nobel Prize winner Par Lagerkvist. The story is told by the dwarf of a Renaissance king—a character who hates humans, loves war, and believes his race is the oldest in the world. From the start of the novel the voice exhibits misanthropy, grandiosity, and self-hatred—conflicts that build as the story progresses. Lagerkvist wrote The Dwarf in 1945 to protest the war; it remains fresh and vital sixty-five years later.

A Blessing on the Moon, Remainder and The Dwarf are all informed by tight control of the voice behind the voice that is telling the story. Each invisible narrator works with an unerring compass that helps ground the reader in an imaginative world.

7 January 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.