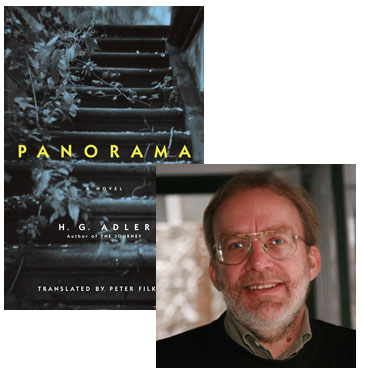

Peter Filkins on Taking In H.G. Adler’s Panorama

I started reading H.G. Adler’s Panorama over the long weekend, and I’m still early in, but I’m blown away by the way that Peter Filkins has rendered Adler’s flowing narrative voice, details tumbling one after the other as filtered through the perspective of a young child, not quite as poetic and pointillist as the early pages of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man but setting down into words a similar sense of wonder. (I know enough to know that the boy will grow up, and his experiences will become much less wonderful, but that foreknowledge isn’t stopping me from being captivated by each page I see now.) Here, Filkins talks about the challenges of rendering into English not just the words Adler wrote, but the consciousness with which he infused them.

The phrase “lost in translation†usually refers to what fails to be carried over from the original to the target language. However, in taking on the novels of H.G. Adler, I have often felt lost to and utterly consumed by the subtlety of Adler’s prose and the uncanny way that the consciousness of the author remains always at one remove from the narration itself, and yet present in every sentence. This was most obvious when I translated the Holocaust phantasm of Adler’s novel The Journey, for there the multiplicity of anonymous voices obliquely tied to the oppressors and their victims served as the woven fabric of Adler’s own present sensibility amid the prose. In Panorama, this at first seemed less obviously so, for as a species of Bildungsroman it uses an omniscient third-person narrator to render the more straightforward development and life of Josef Kramer, the book’s protagonist.

But like that other Josef K. of further renown, Josef Kramer remains a kind of cipher through which passes the people and places that he initially witnesses, and that eventually define him. The more Josef Kramer experiences and observes, the more the consciousness at work within him grows through its ability to absorb experience, survive it, and relive it through memory. Because Josef is a survivor, it is his memory that narrates Panorama, though at the start the reader is not overtly made aware of this. As the novel proceeds and Josef grows from child to schoolboy living in post-World War I Bohemia, then to university student to young man witnessing the cataclysm that drags him through the horrors of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Langenstein, the reader begins to understand that it is Josef who is narrating the story of Josef, himself “aware of no break between yesterday and today.†Indeed, as an exile in England at the book’s close, Josef realizes “the past is so transparent in its intrusion that it no longer relates to any so-called ‘I’ or ‘you’, nor is Josef sure any longer whether he is someone who has acted or is a witness or a victim, or whether he is all of these together….â€

18 January 2011 | in translation |

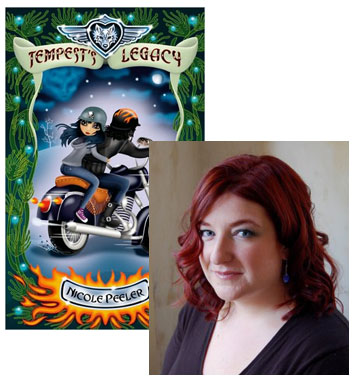

Censoring Past & Present: Nicole Peeler on Teaching Huckleberry Finn

If you’ve been reading Beatrice for a while, you might remember that I named Nicole Peeler‘s debut novel, Tempest Rising, as one of my favorites for 2009—last year, she published a sequel, Tracking the Tempest, and just a few days ago Tempest’s Legacy came out. (I can’t wait to get up to speed!) When she’s not bringing a fresh spin to paranormal romance, Nicole teaches English literature and creative writing as an assistant professor at Seton Hall, and when the controversy broke last week over that bastardized edition of Huckleberry Finn, she had strong reactions, and I invited her to share her thoughts with us.

In the fall of 2008, I began my first teaching job as an assistant professor of English Literature at Louisiana State University in Shreveport. I’d just completed my doctorate in English Literature at the University of Edinburgh, in Scotland, and had lived overseas for over six years. Born near Chicago, I’d done my undergraduate degree in Boston. In other words, I was a thoroughgoing Yankee freshly transplanted to the South, and I was suddenly teaching Americans when I’d only ever taught Europeans. Any culture shock, however, didn’t discourage me, and I jumped into the new job with my usual naive gusto.

And so, when I received the textbook I was to use for a 200-level, non-major’s, “introduction to literature” course, I was thrilled to see one of my very favorite short stories by Flannery O’Conner, “The Artificial Nigger.” I adore this particular work, and immediately added it to my reading list. Only to find myself, about halfway through the semester, staring nervously at my syllabus in front of a roomful of students, about one-third of whom were African-American. For that’s when it dawned on me that I—the Caucasian Yankee, who’d never lived in the South, and hadn’t lived in the US for years—was about to have to say the word “nigger,” in public, a lot. I had to wonder how this would fly.

11 January 2011 | uncategorized |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.