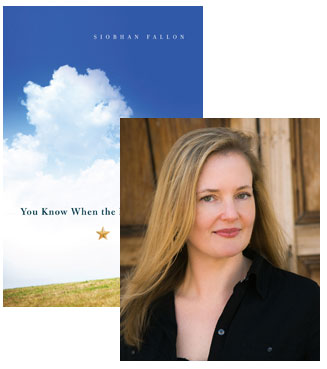

Siobhan Fallon Picks Up “The Things They Carried”

Siobhan Fallon knows about the cost of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan on the families of American soldiers—she lived at Fort Hood, Texas, while her husband served two tours of duty. The stories in You Know When the Men Are Gone show us how the prolonged separation stresses the emotional seams of marriages and families, and how what happens to one soldier can affect an entire community, as peripheral characters in one story are brought into closer focus later on. Stories like “Camp Liberty” and “The Last Stand” also address what happens to the soldiers themselves, the ways combat duty reshapes their own relationships with their domestic lives. In writing this collection, and fitting its stories together just so, Fallon drew some of her inspiration from one of the greatest chroniclers of the 20th-century American military experience, as she explains in this essay.

When I was getting my MFA at the New School in New York City, I came across Tim O’Brien’s short story, “The Things They Carried.” This was 1999, before I met my army officer husband, before I, or my classmates for that matter, had any inkling that war could touch us in the middle of New York City. As soon as I read the opening line (“First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl name Martha”), I knew that this would not just be the story of a battle or firefight or even Vietnam, but something that encapsulated hope, a longing for home, and everything in-between. And I was right. “The Things They Carried” packed the same devastating punch when I was a civilian, certain of my safety in the world, as it does now that I am an army spouse with a husband who has served three year-long deployments to the Middle East.

Tim O’Brien never holds back. The reader is told the climax in the second paragraph: Ted Lavender will die. This is mentioned over and over again and yet it is no less shocking when it actually unfolds in a scene. O’Brien deftly uses repetition, turning the characters and their possessions over and over again in his hand, holding them out for the reader’s inspection, until the lines almost become a chant, creating a rhythm to accompany the soldiers’ endless walking, a literary cadence. Each retelling reveals a little bit more of the story, revisiting each angle and seemingly mundane detail that will loom extraordinary when Ted Lavender is shot in the head.

20 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Read This: Among Others

Yesterday, Shelf Awareness ran my review of Jo Walton’s Among Others, a novel that masterfully blurs the lines between “fantasy” and “literary” fiction, and between “adult” and “YA” novels, in a beautifully compelling story about a teenage girl who has trouble getting along with anybody else at her boarding school and spends most of her time reading science fiction and fantasy novels.

Yesterday, Shelf Awareness ran my review of Jo Walton’s Among Others, a novel that masterfully blurs the lines between “fantasy” and “literary” fiction, and between “adult” and “YA” novels, in a beautifully compelling story about a teenage girl who has trouble getting along with anybody else at her boarding school and spends most of her time reading science fiction and fantasy novels.

OK, that’s a deliberately glib description. Morwenna Phelps is a teenage girl, and she has been sent to a boarding school after a family tragedy, and she is a huge SF/F fan—with definite tastes that will be instantly recognizable to any fan who came of age around 1979, when this novel is set. (My own science fiction awakening began in earnest about five years later, and though it didn’t follow the exact trajectory Mori’s does, the terrain is intimately familiar.) But the references to Heinlein and Tolkien and Zelazny aren’t so in-jokey that people with no background in the genres can’t follow along, and in any case the core of the novel isn’t “Mori reads the classics” but “Mori struggles to make sense of this massive trauma that took place offstage, just before our story kicks into gear.” And, as Cory Doctorow notes in his review, “these books are not an escape for her… [but] a whole cognitive and philosophical toolkit for unpicking the world, making sense of its inexplicable moving parts, from people to institutions. This isn’t escapism, it’s discovery.”

Doctorow embraces the fantasy elements of the novel quite readily in his review, but I’m a bit more skeptical—and I think one of Walton’s most brilliant achievements here is that, by telling the story through Mori’s perspective, she makes it possible for both readings to be correct, with the reader being forced to choose which one to believe. In my review, I compared Among Others to another possibly magical story about a teenage girl, Frank Portman’s Andromeda Klein; both novels reinforce a point I’ve made over and over here: If your story is good enough and true enough to its own internal compass, you can put it on any superficially appropriate shelf in the bookstore and the right readers will discover it.

19 January 2011 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.