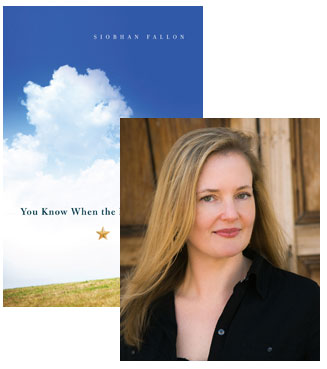

Siobhan Fallon Picks Up “The Things They Carried”

Siobhan Fallon knows about the cost of the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan on the families of American soldiers—she lived at Fort Hood, Texas, while her husband served two tours of duty. The stories in You Know When the Men Are Gone show us how the prolonged separation stresses the emotional seams of marriages and families, and how what happens to one soldier can affect an entire community, as peripheral characters in one story are brought into closer focus later on. Stories like “Camp Liberty” and “The Last Stand” also address what happens to the soldiers themselves, the ways combat duty reshapes their own relationships with their domestic lives. In writing this collection, and fitting its stories together just so, Fallon drew some of her inspiration from one of the greatest chroniclers of the 20th-century American military experience, as she explains in this essay.

When I was getting my MFA at the New School in New York City, I came across Tim O’Brien’s short story, “The Things They Carried.” This was 1999, before I met my army officer husband, before I, or my classmates for that matter, had any inkling that war could touch us in the middle of New York City. As soon as I read the opening line (“First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl name Martha”), I knew that this would not just be the story of a battle or firefight or even Vietnam, but something that encapsulated hope, a longing for home, and everything in-between. And I was right. “The Things They Carried” packed the same devastating punch when I was a civilian, certain of my safety in the world, as it does now that I am an army spouse with a husband who has served three year-long deployments to the Middle East.

Tim O’Brien never holds back. The reader is told the climax in the second paragraph: Ted Lavender will die. This is mentioned over and over again and yet it is no less shocking when it actually unfolds in a scene. O’Brien deftly uses repetition, turning the characters and their possessions over and over again in his hand, holding them out for the reader’s inspection, until the lines almost become a chant, creating a rhythm to accompany the soldiers’ endless walking, a literary cadence. Each retelling reveals a little bit more of the story, revisiting each angle and seemingly mundane detail that will loom extraordinary when Ted Lavender is shot in the head.

“The Things They Carried” isn’t a very long story, just twenty-six pages in my paperback edition of The Things They Carried, and yet it seems to touch upon everything. It is, of course, a war story with the bullets and blood you’d expect; with its soldiers, swiftly drawn and vivid, a pack of boys filled with a deadly fear of embarrassment that motivates them to do acts that might later be claimed as brave. But the objects they cling to make the story transcend every genre. Their possessions offer an escape as well as insight into pasts that have nothing to do with soldiering: Jimmy Cross rereading Martha’s coolly platonic letters, longing for her love while sucking on the beach pebble she mailed him; Ted Lavender, always so scared, popping tranquilizers and keeping a fat stash of dope in his rucksack; Henry Dobbins with his extra rations of canned peaches in heavy syrup; Kiowa with his grandfather’s hatchet, each night falling asleep with his head on his bible as if it was a pillow.

While The Things They Carried tells the stories of Jimmy Cross and his soldiers, in You Know When the Men Are Gone, I try to tell the stories of the Marthas, of the spouses who write the letters and send the care packages, as well as the ones who don’t. I try to trace the origins of the objects the young men carry as much in their minds as in their rucksacks, those things that conjure up the idea of home. For all the soldiers counting the days they are away, there are families who are also waiting, fighting their own battles and fears, filling calendar squares with x’s, hoping their soldiers will arrive whole and safe, trying their best to be there when they return.

Tim O’Brien, in his story about a platoon outside the village of Than Khe, Vietnam, perfects what I am trying to do in stories about the families of Fort Hood, Texas: He gives the reader a mere glimpse and it is enough to show us an entire world.

20 January 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.