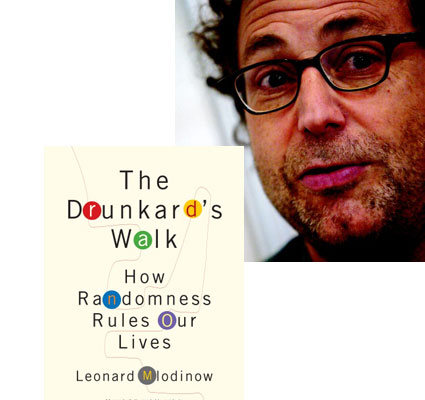

Leonard Mlodinow on Publishing’s Vagaries of Chance

Leonard Mlodinow’s new book, The Drunkard’s Walk is about the surprising and misunderstood role that randomness plays in people’s fate, and, as Mlodinow himself observes, “Those who study randomness—or write books for Pantheon about it—are not immune to its effects.” He reports on some of the odd twists that have befallen other researchers into randomness: The 16th-century scholar Gerolamo Cardano, who couldn’t find a publisher for his Book on Games of Chance, made a fortune as a doctor based on a recommendation to one patient that didn’t really work; Blaise Pascal’s breakthroughs in probability theory emerged from a gambling habit he developed on what was supposed to be a restful retreat in Paris; Adolphe Quetelet went to Paris to study astronomy but got sidetracked into statistics and made his reputation in that newly developing field; Edward Norton Lorenz’s elaboration of the butterfly effect was the result of an attempted computational shortcut resulting in massive errors. “These lives might be outliers,” Mlodinow says. “Or they could be archetypes.” In the meantime, what’s going to happen to his book? The only thing he knows is that we just don’t know.

Now that I have finished this book, it is time for me to stare randomness in the face myself, to adjust my thinking and my expectations according to the principles I have espoused. Will this book succeed? Like most books, it was a labor of love. But all I can control are the words, and now that those words are almost completed Pantheon is focusing on what they can make happen, formulating the very plans that, through some chain of events, eventually led you to read this. These days a publishing plan represents an effort so thoroughly thought out and researched that even if you are only interested in this volume because you thought The Drunkard’s Walk would be a self-help book, the marketing department has probably accounted for you in one way or another. And so as I prepare to relinquish my offspring to their earnest efforts, I must confront the tendency to believe that they are in control, and later another tendency to judge my work on the basis of how many people cared to read it, or what might be said (or worse, not said) about it.

But I didn’t just write the book, I read it. (At least a dozen times). So before I take my publisher’s early excitement over the manuscript too seriously, I remind myself that this is the industry that rejected George Orwell’s Animal Farm, because “it is impossible to sell animal stories in the U.S.;” turned down Isaac Bashevis Singer because “it’s Poland and the rich Jews again;” and dumped a young Tony Hillerman, imploring him to “get rid of all that Indian stuff.” One book in the 1950s was repeatedly rejected by publishers who responded to the manuscript with criticism such as “very dull,” “a dreary record of typical family bickering, petty annoyances and adolescent emotions,” and “even if the work had come to light five years ago, when the subject [World War II] was timely, I don’t see that there would have been a chance for it.”

That book, Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, has since sold 30 million copies, making it one of the bestselling books in history. And John Kennedy Toole, after his many rejections, lost hope of ever getting his novel published and committed suicide. His mother, however, persevered, and eleven years later A Confederacy of Dunces was published, won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and sold 1.5 million copies.

21 May 2008 | guest authors |

Read This: Ron Hogan’s SF Debut: Free!

Subterranean Press has just created a free PDF download of John Scalzi’s special cliché-driven issue of Subterranean, the science fiction magazine that includes the short story “In Search of…Eileen Siriosa,” an untold tale from my research for The Stewardess Is Flying the Plane!. As Scalzi says:

“Just about every writer out there has a story they would dearly love to do but could never justify actually writing, because its very beating heart is a cliché so old and worn out that there would be no chance of actually selling it—clichés so advanced in years that even Hugo Gernsback would send back the story with a handwritten note: ‘Look, kid. It’s been done.’ And now, finally, an excuse to bang that story out! It’s like Christmas!”

13 November 2006 | read this |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.