Jem: The Science Fiction Novel the Literary Establishment Embraced

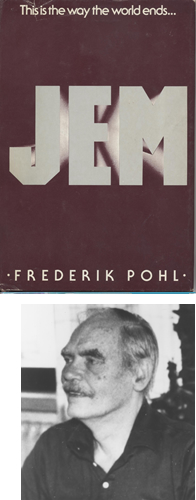

The National Book Foundation is celebrating the 60th anniversary of the National Book Awards by looking back at every one of its fiction winners, and the first contribution I’m making to the series is an appreciation of Frederick Pohl’s Jem, the first and only winner of an American Book Award (1980 was a strange year for the Foundation) for hardcover science fiction.

The National Book Foundation is celebrating the 60th anniversary of the National Book Awards by looking back at every one of its fiction winners, and the first contribution I’m making to the series is an appreciation of Frederick Pohl’s Jem, the first and only winner of an American Book Award (1980 was a strange year for the Foundation) for hardcover science fiction.

It’s only a few paragraphs, but I explain why the American Book Award for science fiction didn’t go along with the Hugo and Nebula commendations, and how certain aspects of Pohl’s novel find resonance with other authors from Charles McCarry and Ted Mooney to Jonathan Lethem and Junot Diaz. Unfortunately, it’s really hard to find Jem in the U.S., but if you put in the effort I’m pretty sure you won’t be disappointed.

13 August 2009 | read this |

Nic Brown’s Perfect Storm (For Writing about “People and Some Dogs,” That Is)

I don’t remember much about Hurricane Hugo; in September 1989, I was already deep into my sophomore year of college in the middle of Indiana, well out of hurricane country. But as Nic Brown points out in this essay about his new collection of “Hugo stories,” Floodmarkers, I don’t really need to know that much about what happened then. I remember what it was like getting stuck in Hurricane Bob two years later—a lot of not-much-happening punctuated by rain and wind—and once you get past that, you can begin to relate to Brown’s characters on more fundamental levels, discovering the variety of responses they have to a simple external event.

In North Carolina, where I live, Hurricane Hugo is never discussed. Hurricane Fran, which devastated the state in 1996, tops the conversational list when it comes to Carolina catastrophe. Hugo hit years earlier, in September 1989, and wreaked havoc on Charleston (which is in South Carolina, folks) and then moved up into Charlotte with a wallop. At the time, it was the most destructive storm since Hazel in 1954. The Katrina of Charleston, I’ve heard it called since (which is hyperbole, of course, but you get the idea). Then Fran arrived, and was worse. I guess this is when Hugo disappeared from conversation.

But if you mention Hugo—if you bring it up directly—everyone here has a story. Rarely are these momentous in the near-death or total destruction sort of way. Usually they’re more like, “I didn’t even know the storm was coming and then a branch landed on my car and the electricity went out and I got in a fight with my brother.” This is why Hugo worked well for my fictional purposes.

Floodmarkers is a linked collection of stories set during the day Hugo blows through the fictional North Carolina town of Lystra. But the book isn’t about Hugo. It’s about the people living in Lystra and the ways the storm changes their daily lives just enough to make room for the singular to occur. Lystra is set in the Piedmont, where only the edge of Hugo reached. If I had set the book in Charleston, or even Charlotte, it would have run the risk of becoming a historical fiction about a Hugo. And I don’t care about Hugo. Because Hugo is a storm, and to tell you truth, when it comes down to it, I really only care about people. And some dogs. So the book is about people. And some dogs.

27 July 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.