Life Stories #90: Barbara Schoichet

Barbara Schoichet got hit with a triple whammy just before her fiftieth birthday—she lost her job at a movie studio in Los Angeles, her girlfriend left her, and then her mother died. Don’t Think Twice is the story of how she pushed back against all that by learning to ride a motorcycle, then flying out to New York to buy a Harley Davidson and ride it back home across the country. Almost immediately, she got first-hand experience of the camaraderie that exists between Harley drivers, through random acts of kindness on the road… and that was something she wasn’t entirely prepared for:

“To be honest with you, I kinda had a death wish. I didn’t care whether I came back. I just wanted to divert my mind from all that was going on in my life. And one of the best ways to divert grief is to focus on something else. I focused on staying alive. It’s interesting, because I had a death wish, but I was really searching for a life wish. I mean, the great thing about this trip was all I had to think about was staying upright and getting to the next town I was going to stop at, and looking at every nook and cranny in the road, making sure I didn’t hit something. It really healed me, because by the time I got back, I thought I could do anything.”

Listen to Life Stories #90: Barbara Schoichet (MP3 file); or download this file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click). Or subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes, where you can catch up with earlier episodes and be alerted whenever a new one is released. (And if you are an iTunes subscriber, please consider rating and reviewing the podcast!)

photo: Nancy Borowick

2 May 2017 | life stories |

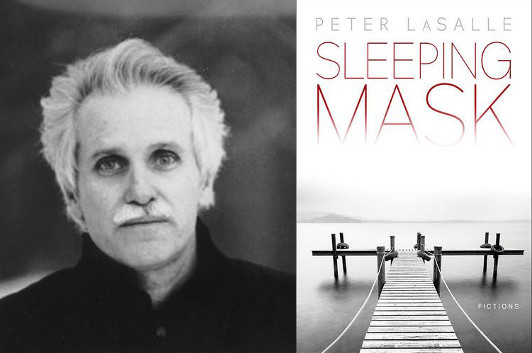

Peter LaSalle’s Pursuit of Borges

photo: Alex S. MacLean

There’s some odd little moments in Peter LaSalle’s Sleeping Mask. And I’m not just thinking about the story where a man walks out of an airplane lavatory and slowly begins to realize he’s somehow wound up on an otherwise empty plane, still en route to… well, he’s not quite sure. There’s also the couple that dines at a restaurant in a Mexican border town and never realizes that it’s been taken over by a local drug lord, or the child soldiers who decide to kidnap the girls from a local orphanage and quickly find themselves no longer in charge of the situation. Even the more quotidian stories, like the day in the life of a university professor, have a detached, almost abstract quality to them. And then there’s the one about Edgar Allan Poe that’s a pitch-perfect academic paper… actually, that’s probably a good segue into this essay, where LaSalle pays tribute to another writer who liked to play with the boundaries between reality and fiction as well.

Well, when it comes to my inspiration as a short story writer, even awe, I often acknowledge the Argentine master of the genre, Jorge Luis Borges, and the collection Ficciones. It’s a book that by dint of sheer innovation—summoning the metaphysical, bravely and somehow magically pushing against the limits of past literature, a true clarion call announcing postmodernism—probably widened the possibilities of serious fiction forever after first appearing from a small Buenos Aires publisher in 1944.

I can admit it was a rather meandering road that eventually led me to such admiration. Oddly, I saw Borges before I’d ever read a word of his work. I was a Harvard sophomore in 1967 and my roommate was a fellow English major, a guy more sophisticated than me in matters literary (though one wonders how sophisticated either of us could be, he from a suburban Salt Lake City high school and I from an unknown private Catholic boys school, a pretty medieval operation, in the nowheresville of semi-rural Rhode Island). Excited, he told me that a very important writer was on campus to lecture that year, under of the auspices of the long-established and prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures series. He assured me that this Jorge Luis Borges was a figure easily on par with Beckett and we must attend.

So one snowy Cambridge evening we set out together to Sanders Theatre, a big teacup of a lecture hall in the campus’s old, spookily turreted Memorial Hall. I watched a smiling blind man being led onto the stage; his hair was silvery, his black suit well tailored. He spoke with a rather antiquated British accent, and I know I didn’t understand much of what he said. My lack of comprehension wasn’t because of the accent but due to the fact that the content was obviously well beyond me at the time: deep insight concerning the mystery of metaphor, also the paradoxically illogical logic of dream in literature, etc.—such being some of his subjects, as I learned later when reading a book that transcribed those Harvard talks.

I guess what stuck with me at age 20, above all else, was the very image of him, elderly, blind, continuing to gently smile and erudite to a dazzling degree—he appeared nothing short of Homeric, an archetypical Poet and icon for Literature itself, all right.

24 April 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.