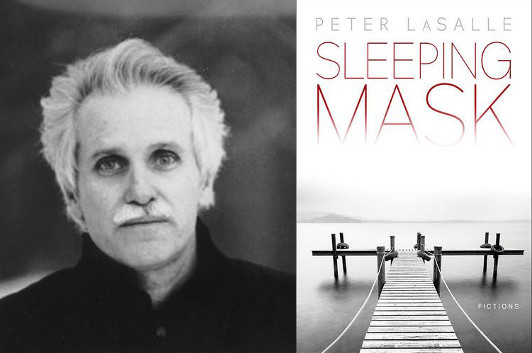

Peter LaSalle’s Pursuit of Borges

photo: Alex S. MacLean

There’s some odd little moments in Peter LaSalle’s Sleeping Mask. And I’m not just thinking about the story where a man walks out of an airplane lavatory and slowly begins to realize he’s somehow wound up on an otherwise empty plane, still en route to… well, he’s not quite sure. There’s also the couple that dines at a restaurant in a Mexican border town and never realizes that it’s been taken over by a local drug lord, or the child soldiers who decide to kidnap the girls from a local orphanage and quickly find themselves no longer in charge of the situation. Even the more quotidian stories, like the day in the life of a university professor, have a detached, almost abstract quality to them. And then there’s the one about Edgar Allan Poe that’s a pitch-perfect academic paper… actually, that’s probably a good segue into this essay, where LaSalle pays tribute to another writer who liked to play with the boundaries between reality and fiction as well.

Well, when it comes to my inspiration as a short story writer, even awe, I often acknowledge the Argentine master of the genre, Jorge Luis Borges, and the collection Ficciones. It’s a book that by dint of sheer innovation—summoning the metaphysical, bravely and somehow magically pushing against the limits of past literature, a true clarion call announcing postmodernism—probably widened the possibilities of serious fiction forever after first appearing from a small Buenos Aires publisher in 1944.

I can admit it was a rather meandering road that eventually led me to such admiration. Oddly, I saw Borges before I’d ever read a word of his work. I was a Harvard sophomore in 1967 and my roommate was a fellow English major, a guy more sophisticated than me in matters literary (though one wonders how sophisticated either of us could be, he from a suburban Salt Lake City high school and I from an unknown private Catholic boys school, a pretty medieval operation, in the nowheresville of semi-rural Rhode Island). Excited, he told me that a very important writer was on campus to lecture that year, under of the auspices of the long-established and prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures series. He assured me that this Jorge Luis Borges was a figure easily on par with Beckett and we must attend.

So one snowy Cambridge evening we set out together to Sanders Theatre, a big teacup of a lecture hall in the campus’s old, spookily turreted Memorial Hall. I watched a smiling blind man being led onto the stage; his hair was silvery, his black suit well tailored. He spoke with a rather antiquated British accent, and I know I didn’t understand much of what he said. My lack of comprehension wasn’t because of the accent but due to the fact that the content was obviously well beyond me at the time: deep insight concerning the mystery of metaphor, also the paradoxically illogical logic of dream in literature, etc.—such being some of his subjects, as I learned later when reading a book that transcribed those Harvard talks.

I guess what stuck with me at age 20, above all else, was the very image of him, elderly, blind, continuing to gently smile and erudite to a dazzling degree—he appeared nothing short of Homeric, an archetypical Poet and icon for Literature itself, all right.

I subsequently read his short stories. In fact, suddenly it seemed everybody was doing so then in the late 1960s and ’70s, the peak of his popularity. And I mean everybody. While it might have just been a set designer’s prop idea, there comes a telling moment in the 1970 movie Performance, starring Mick Jagger as a rocker living in a ramshackle London flat with groupie companions; in one scene Mick is shown in a bathtub relaxing and reading a paperback book by—of course—Borges.

Still, I doubt that even on first reading Borges I was ready to savor exactly what he was up to, not yet at a point in my own writing life where I could definitely learn from him.

It was only later, in a second, more intense delving into his work in middle age (which included a several-thousand mile trip to Buenos Aires to tap into the geographical atmosphere of the master there, I became so obsessed) that I fully savored his ground-breaking accomplishment. Stories like the wonderfully tangle-titled “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbus Tertius,” where an imaginary planet exists because entries with details on its life and customs are found in a real encyclopedia. Or the hauntingly resonating “The Library of Babel,” where a library floating in a timeless netherworld contains a massive inventory of books, then books about those books, then books about those books, and so on, while the entire vertiginous idea of it perhaps foretells—as commentators have pointed out—the infinite informational limitlessness of the internet yet to arrive.

Actually, for years I had been making occasional tentative forays into metaphysical territory in my own short stories (narratives questioning common assumptions about time and space, reality and unreality, some found in this new collection Sleeping Mask), but it wasn’t until then, in middle age and rereading of Borges—slowly and oh so carefully—that I experienced a heady, illuminating clarity, nothing short of a definition right before me on Borges’s pages of what I had long been groping around for in my own writing.

All of which is to say, I have my personal pantheon of short story writers—Maupassant, Hemingway, Cheever, GarcÃa Márquez, and Joyce Carol Oates among those also prominently enshrined there—but it is with Borges that I experienced maybe the most important thing when it does come to how the work of another writer can make you at last get a good bead on the goal of your own writing quest. Or, to paraphrase a statement of the French poet Baudelaire, as he once wrote concerning his own immersion in the stories of of Edgar Allan Poe:

“This man intrigues me so—he has dreamed my own dreams.”

24 April 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.