Life Stories #95: Lauren Collins

Back in 2016, I had a fantastic conversation with Lauren Collins, a staff writer with The New Yorker who had just published When in French: Love in a Second Language, which is simultaneously a personal story about how Collins fell in love with a French man without really knowing the language—he spoke perfect English, sure, but there was still a significant aspect of his life, his personality, his identity that was closed off to her until she could become fluent—and a broader account of how language helps shape the way we see the world, and how we work to maintain control over that power. (In particular, I’m thinking about how the French government has an académie whose job it is to maintain the purity of the language, coming up with alternatives to pesky English words that threaten to slide into usage.)

How, I wondered, had Collins decided to combine her personal narrative with the reportage and research? “I had never really dabbled in memoir,” she explained…

“I mean, I’m a huge reader of memoir; I’ve always loved it. I’m a huge admirer and student of the genre, but I had just had drilled into my skull at The New Yorker you don’t write I. And if you do, you’d better really earn every single one of those.

So it wasn’t my natural inclination to write something personal. That said, here I am in my personal life, just becoming totally obsessed by and immersed in French—and I’m eating and drinking and breathing and reading and sleeping and… not yet dreaming, but I’m totally into French, and I think as a writer, any time, you know, no matter how much you might think the spheres are going to remain separate…

I mean, I thought, you know, this has nothing to do with my work, this is something I’m doing for love… But once something grabs hold of your mind like that, I think as a writer it just inevitably spills over into what you’re doing professionally. And so the more I thought about it, incrementally, it became clear to me this story was so much richer if I explained why I cared about all this stuff, which was the very, very personal story.”

Sorry this episode has languished in the editing queue for so long! It’s been a bit of a crazy year, but I’m catching up now, and you should keep an eye out for more episodes as I work through that backlog and conduct some new conversations…

Listen to Life Stories #95: Lauren Collins (MP3 file); or download this file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click). Or subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes, where you can catch up with earlier episodes and be alerted whenever a new one is released. (If you’re already an iTunes subscriber, please consider rating and reviewing the podcast!)

photo: Philip Andelman

17 November 2017 | life stories |

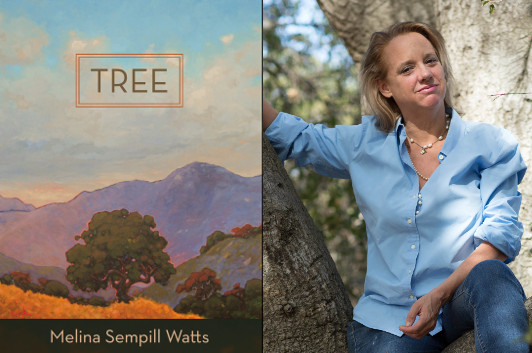

Melina Sempill Watts: The Roots of Tree

photo: Elizabeth Jebef, Eyebright Studios

Every author faces a challenge in coming to understand their characters, but Melina Sempill Watts set herself a particularly tough task, in that the protagonist of Tree is, well, a tree, named Tree. Watts has to figure out the perspective of a character whose ideal lifespan makes human life seem brief by comparison; she has to figure out whether trees can communicate with other lifeforms and if so how; she has to figure out how drama and character momentum work when your main point of view character is literally rooted to the ground… Like I say, a significant challenge! In this essay, Watts explains what makes her feel passionately enough about the subject to take that challenge on.

Babies are made—most times—from love. What are books made from?

In the case of Tree, the intellectual grounding of the novel’s world came from two major strands. The emotional center of the book stems from a secret.

The first strand stems from my lifelong passion for California history, reverence for Chumash culture, a crush on the Californio era and from pieces of my own childhood, when I watched the growth of suburbia sneak up and over the green hills in the Santa Monica Mountains.

The second strand came from focusing on biology and ecological history: how did the ecosystems of Southern California transform over time, how did different cultures push plant and animal communities into new forms? The most radical transition, initially, was to grasslands, when species coming from Spain and other European communities took over. Research looking at what plants were used in the adobe bricks from the oldest European buildings on the Western side of the United States, shows that transition was nearly immediate.

23 October 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.