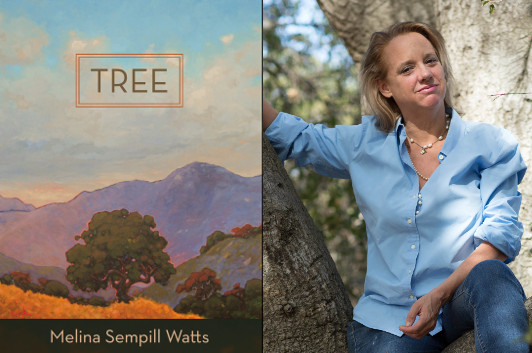

Melina Sempill Watts: The Roots of Tree

photo: Elizabeth Jebef, Eyebright Studios

Every author faces a challenge in coming to understand their characters, but Melina Sempill Watts set herself a particularly tough task, in that the protagonist of Tree is, well, a tree, named Tree. Watts has to figure out the perspective of a character whose ideal lifespan makes human life seem brief by comparison; she has to figure out whether trees can communicate with other lifeforms and if so how; she has to figure out how drama and character momentum work when your main point of view character is literally rooted to the ground… Like I say, a significant challenge! In this essay, Watts explains what makes her feel passionately enough about the subject to take that challenge on.

Babies are made—most times—from love. What are books made from?

In the case of Tree, the intellectual grounding of the novel’s world came from two major strands. The emotional center of the book stems from a secret.

The first strand stems from my lifelong passion for California history, reverence for Chumash culture, a crush on the Californio era and from pieces of my own childhood, when I watched the growth of suburbia sneak up and over the green hills in the Santa Monica Mountains.

The second strand came from focusing on biology and ecological history: how did the ecosystems of Southern California transform over time, how did different cultures push plant and animal communities into new forms? The most radical transition, initially, was to grasslands, when species coming from Spain and other European communities took over. Research looking at what plants were used in the adobe bricks from the oldest European buildings on the Western side of the United States, shows that transition was nearly immediate.

As to the plants themselves, as early as Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose in India, over a hundred years ago, research to determine whether plants can communicate electrically began. Sadly, the data behind the 1970s bestseller The Secret Lives of Plants was never found duplicable, nearly killing off the idea. But then Dr. Suzanne Simard burst onto the scene in the ’90s with research positing that trees were able to use fungal pathways between their roots to talk… albeit very slowly… to one another and even, to transmit food and water. In The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben points out compelling current work to explore electrical communication between plants.

The new science enchanted me. Why? This part is the secret: In my freshman year at University of California San Diego, feeling incredibly lonely, isolated, unloved, I faced a solitary Friday night by stretching out on the quad on a lawn of green grass in the still warmness of early dark. And the grass near my face began, for lack of a better way of articulating it, emoting at me. Then the grass near my chest, the grass near my legs and toes and fingers and through my hair joined in this energetic silent conversation. From an external perspective, there was nothing to hear or see, but it felt like when sunlight bursts through a thick cloud with each new voice joining in… and grass talked to grass and talked to grass, somehow communicating to their peers that I could, again, for lack of a better word, hear the plants.

And they all joined in consoling, greeting and cheering me and I felt as radiant as a newborn the first time he sees his mother’s eyes: It was absolute euphoria. And these plants’ gift has stayed with me my whole life. That absolute magic is what drove me to write Tree, this book is for that field of grass.

I love California live oaks the way grade school girls love horses, with a deep intensity that most adults, women and men, feel compelled to hide when it is not attached to a human romantic interest (a love our culture agrees is acceptable and normal.) Trees that I have experienced are, in general, again, for lack of a better word, louder than grass—and the idea of centuries of life in one spot fascinated me. What is it like to be in one place for a whole existence? How do trees interrelate with all the biota that rises and falls around them? What emotions do trees experience? Only through a novel could I allow answers that stemmed from raw mystical experience to upwell.

After a sober career working on watershed/ecosystem resource issues at a Resource Conservation District, it took considerable audacity to publish a novel about a tree that is written from the perspective of at tree. But as I learned from Andy Lipks, founder of TreePeople, if you ask someone about his or her favorite tree, everyone has a favorite tree. So maybe we’ve all been talking to trees all along. Read Tree and see.

23 October 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.