Should Indies Compete with Amazon on Pricing?

There’s been a lot of hype recently about the Indiebound reader app, which was developed by the American Booksellers Association’s Indiebound program to encourage consumers to buy Google eBooks from their local independent bookstores rather than buying Kindle-formatted ebooks from Amazon. (Yes, I spelled “ebooks” two different ways; in the case of Google, it’s trademarked with a capital B.) One of the chief selling points of this campaign is the assertion that you can buy ebooks from indies for the same price as Amazon. Unfortunately, while this is true in principle, it is not universally true in practice.

As many of you know, the “Big Six” publishers—the New York-based conglomerates generally, for better or for worse, acknowledged as the “core” of the book publishing industry—price their ebooks according to what’s known as the “agency model.” This means, that rather than charging booksellers a wholesale price, after which the bookseller can charge consumers a retail price of its own choosing, these publishers have chosen to set a fixed price for their ebooks, and then authorize individual retailers to sell those ebooks at that price. The only way the price changes is if the publisher decides to change it, and no retailer has a competitive price advantage.

Any ebooks from those publishers, then, do cost the same when purchased through an independent bookstore as they would at Amazon, or Barnes & Noble, or the Google eBookstore. So Robert K. Massie’s Catherine the Great, published by Random House, is $14.99 wherever you go, including Powells.com, the indie bookstore with whom I’ve had a commission-based relationship for several years. But what about ebooks from publishers who don’t use the agency model? Let’s look at Stephen Greenblatt’s National Book Award-winning The Swerve, published by W.W. Norton, as one example. On the day I’m writing this post, the Amazon Kindle edition is $9.43, a price that the Google eBookstore matches. If you want to read this book on a Barnes & Noble Nook, though, it’s $14.01—which is still a significant savings from the $23.92 you’d pay to buy the ebook from Powell’s. And at least one independent bookstore is charging the sticker price of $26.95.

It’s also worth considering that some independent publishers have Kindle-compliant digital editions for sale through Amazon with no counterpart editions available at the Google eBookstore… and thus not available through independent bookstores working with Google.

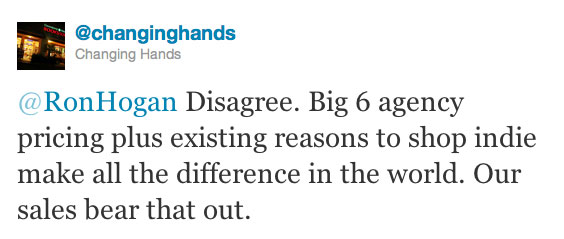

When I raised this issue on Twitter, I observed, “Announcing you charge the same price for an item as a national retailer isn’t impressive when said price is fixed by the manufacturer.” Other folks pointed out, and I recognize the truth in this, that it’s still worth mentioning when that national retailer has a prominent reputation for beating its competitors on price. Brandon Stout, who handles publicity and marketing for Changing Hands, an indie bookstore in Tempe, took further issue with my reasoning:

30 December 2011 | theory |

Book Culture, Social Media, & Monetization

Over the last few weeks, there have been some provocative discussions about people using social media (and other online tools) to monetize literary culture. The debate basically kicked off because of FridayReads, which started out about a year and a half ago as a fun hashtag meme that my friend Bethanne Patrick came up with. Simple premise: If you’re on Twitter on Friday, take a moment to tell people about the book you’re reading, and include a “#fridayreads” in the tweet so it’s easy for people to find in a search. It took time to build traction, but gradually it got to the point where thousands of people are participating each week.

At some point, Bethanne saw the base audience that had grown around the hashtag, and hit upon the idea of getting publishers to pay her to promote books to that audience. With our mutual friend Erin Cox as sales director, FridayReads began running publisher-supported giveaways and author chats. Not everybody knew this was the case, however, and even people who did know about it didn’t necessarily know the extent of the business. This went on until, as I say, a few weeks ago, when Jennifer Weiner called attention to FridayRead’s paid promotions, and one position that emerged from the hue and cry that followed was, in essence, that any reader participating in FridayReads was feeding Bethanne’s marketing machine, rather than supporting an organic book culture.

(It’s worth nothing here that I’m also friends with Jennifer; my respect for people on both sides of this issue enables me to see not just that each has merit, but that each is operating in good faith.)

The short-term solution was easy: Bethanne implemented more overt disclosure practices, making the business nature of FridayReads more apparent. Obviously, that doesn’t comfort people who are outright opposed to people making money off other people’s participation in what they expect to be friendly and non-commercial social media, but short of dismantling the financial operations, little would. To me, the question isn’t so much should Bethanne (or anybody, really) be making money off other people’s willingness to talk about their love of books online, but rather will they do so in as non-exploitative a manner as possible?

On that front, I didn’t have a problem with FridayReads. Once you know about the marketing component, it’s a straightforward proposition: You tell the world what book you’re reading, and there’s a chance—no guarantee—that you might be one of the handful of people who gets a free book. It’s not like Klout, where (as John Scalzi observed, among others) people were told, “Hey, how’d you like a prize for participating in Klout?” and then, when they went to claim that prize, basically told they hadn’t earned it yet. Sheesh.

14 December 2011 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.