Should Indies Compete with Amazon on Pricing?

There’s been a lot of hype recently about the Indiebound reader app, which was developed by the American Booksellers Association’s Indiebound program to encourage consumers to buy Google eBooks from their local independent bookstores rather than buying Kindle-formatted ebooks from Amazon. (Yes, I spelled “ebooks” two different ways; in the case of Google, it’s trademarked with a capital B.) One of the chief selling points of this campaign is the assertion that you can buy ebooks from indies for the same price as Amazon. Unfortunately, while this is true in principle, it is not universally true in practice.

As many of you know, the “Big Six” publishers—the New York-based conglomerates generally, for better or for worse, acknowledged as the “core” of the book publishing industry—price their ebooks according to what’s known as the “agency model.” This means, that rather than charging booksellers a wholesale price, after which the bookseller can charge consumers a retail price of its own choosing, these publishers have chosen to set a fixed price for their ebooks, and then authorize individual retailers to sell those ebooks at that price. The only way the price changes is if the publisher decides to change it, and no retailer has a competitive price advantage.

Any ebooks from those publishers, then, do cost the same when purchased through an independent bookstore as they would at Amazon, or Barnes & Noble, or the Google eBookstore. So Robert K. Massie’s Catherine the Great, published by Random House, is $14.99 wherever you go, including Powells.com, the indie bookstore with whom I’ve had a commission-based relationship for several years. But what about ebooks from publishers who don’t use the agency model? Let’s look at Stephen Greenblatt’s National Book Award-winning The Swerve, published by W.W. Norton, as one example. On the day I’m writing this post, the Amazon Kindle edition is $9.43, a price that the Google eBookstore matches. If you want to read this book on a Barnes & Noble Nook, though, it’s $14.01—which is still a significant savings from the $23.92 you’d pay to buy the ebook from Powell’s. And at least one independent bookstore is charging the sticker price of $26.95.

It’s also worth considering that some independent publishers have Kindle-compliant digital editions for sale through Amazon with no counterpart editions available at the Google eBookstore… and thus not available through independent bookstores working with Google.

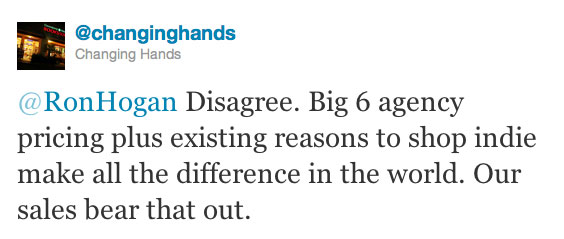

When I raised this issue on Twitter, I observed, “Announcing you charge the same price for an item as a national retailer isn’t impressive when said price is fixed by the manufacturer.” Other folks pointed out, and I recognize the truth in this, that it’s still worth mentioning when that national retailer has a prominent reputation for beating its competitors on price. Brandon Stout, who handles publicity and marketing for Changing Hands, an indie bookstore in Tempe, took further issue with my reasoning:

Stout went on to explain, in response to a query from me, that the store’s spike in ebook sales was significantly greater for Big 6 titles—as I suspected it might be—and that these were, for the most part, the books that were getting the most attention and visibility, the books customers were most likely to want—so it was worthwhile for consumers to be informed that these books were available from independent booksellers at no greater cost than one would pay at Amazon. “With price a non-issue,” he added, “we can convert mind-share into market-share.”

That might be fine, if the assertion that you can buy ebooks from indies for the same price you’d pay at Amazon were universally true, but we’ve already seen that it isn’t. An independent bookstore could make it true by keeping track of the price of every non-exclusive ebook available at Amazon and adjusting its prices to match Amazon’s in all cases. That’s a lot of work, though, not to mention that it would severely cut into that bookstore’s profit margins. (It cuts into Amazon’s profit margins, too, but Amazon has deep pockets, and is willing to make up some of the missed revenue through volume and to take the short-term hit while waiting out the decline of its competitors.) The easier solution would be to say that you could buy “many ebooks” at a price that matches Amazon’s, because that statement is true. I’d encourage independent bookstores to adopt that language, if they’re going to persist in this campaign, if for no other reason than because it’s better to give accurate, true information to your customers.

The bigger question, the one I raised in the title of this post, is whether independent bookstores should even bother to compete with Amazon on the issue of pricing. (As it stands, despite their aggressive language, they generally don’t compete with Amazon on pricing; it’s not a competition if you’re only matching another store’s price because that price has been fixed by the supplier.) There was a lot of chatter about this recently, sparked by an article in Slate in which Farhad Manjoo declared “bookstores present a frustrating consumer experience,” and that they’re “economically inefficient” to boot. If independent bookstores were better at what they did, he argues, they’d be able to slash their prices down to Amazon’s levels. Manjoo then wrote a follow-up column, in which he makes suggestions on how indie bookstores could improve their efficiency.

The majority of Manjoo’s recommendations consistently remove human contact from the things that make shopping in a local bookstore worthwhile. Instead of having a conversation with a bookseller and getting a recommendation that way, Manjoo would like to see bookstores use Amazon customer reviews as shelf-talkers. Instead of having to interact with a bookseller at the cash register, Manjoo wants an app that lets him buy the book he wants electronically and take it home with him. Instead of trying to find an employee when he has a question, Manjoo wants to push a button on his smartphone so somebody will come to him.

![maybe-apps-tweet [Maybe an app will do all this stuff so I don't have to deal with any people!]](http://beatrice.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/maybe-apps-tweet.jpg)

It’s entirely unclear to me how any of Manjoo’s “improvements” to the bookstore retail experience are supposed to increase its efficiency to the point that indies could afford to lower their prices without bringing their profits below their current levels. If this is what it would take for indie bookstores to compete with Amazon on pricing, I’d say to hell with it, and I’m pretty sure most bookstores worth visiting would take the same approach.

30 December 2011 | theory |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.