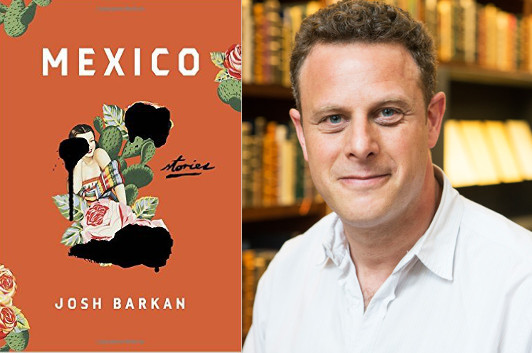

Josh Barkan: The Inner Meat of the Story

photo: Adrian Mealand

Josh Barkan likes to get inside his characters’ heads—deep inside. So while the stories in his second collection, Mexico, are full of action—a chef is forced to surprise a drug lord with a truly astounding entrée; a teacher watches as two students in one of his classes; the children of rival drug lords, enact a Romeo & Juliet-esque drama in another—they’re ultimately about the interior journeys of the narrators. That teacher, for example? He’s also spurred by what he witnesses to rebuild the sundered relationship with his Orthodox Jewish father-in-law. In another story, a woman facing a certain cancer diagnosis listens impatiently as another woman describes how she got a set of horrific scars, only realizing at the end that the story really does hold meaning for her. Here, Barkan talks about some of the inspirations he draws upon as he works his way to finding his characters’ voices.

Short stories often don’t have time for long sections of interior thought, but the traditional reliance on plot to move the short story along seems less interesting to me than finding out the way the protagonist perceives and thinks about the world. Two authors that emphasize such interior perception and thinking are Saul Bellow and Denis Johnson. Bellow rarely wrote short stories—the novel and novellas gave him much more room to follow the long thought processes of his protagonists—but in two stories, “Looking for Mr. Green” and “A Silver Dish,” he showed how great depth of internal thought can be revealed in the short form.

In “Looking for Mr. Green,” a cerebral character, who has trained as an academic, finds himself working in the Depression for a welfare office, delivering checks to the poor. His supervisor laughs at the lack of utility of the protagonist’s university training for such work. But as the protagonist walks around the city of Chicago, trying to find the elusive Mr. Green, he contemplates about what is permanent and what is impermanent, and what his relationship is to the surrounding poor neighborhood that he is experiencing for the first time. Full of self-doubt, the protagonist is finally able to find Mr. Green—or someone who he lets himself believe is Mr. Green—to give the check to, and he is able to come to the conclusion that in the end he “could” find Mr. Green, which ends up reaffirming the validity of all of his cogitating.

In “A Silver Dish,” Bellow’s protagonist faces the loss of the death of his father, and he has to determine whether his father was a crook, who used him for his own selfish ends, or whether his father was trying to liberate him from living a religious life that was not his own. The text moves in and out of the deep interior thoughts of the protagonist, as church bells toll, one week after the death of his father. Complex ideas of love, and that the world was “made for love” are reflected upon, and by the end of the story the protagonist accepts that he is both like and unlike his father in crucial ways—sharing the charisma of his father but not his father’s selfishness.

The depth of such interior thinking creates characters that grapple intellectually with their problems as they experience them. And this is precisely the kind of character that interests me—characters who not only face problems external to themselves but who must think about their predicament. The thinking is both the potential solution and the problem, itself. As Bellow points out, the mind and the body are often at odds. His characters fight within themselves.

6 February 2017 | selling shorts |

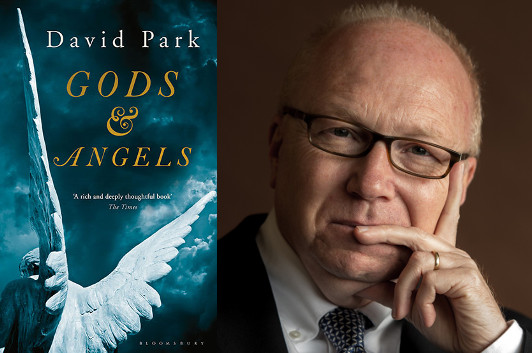

David Park’s Way of Seeing into Lives

photo: Bobbie Hanvey

As I was reading the stories in David Park’s Gods and Angels, I took note of the way he’s able to dig into the emotional lives of his protagonists, whether it’s a teenage boy who’s tired of having to spend the day after Christmas with his estranged (and clinically depressed) mother, or a middle-aged man who’s struggling, during a weekend getaway, to find a way to relate to one of his best mates (who’s also coping with depression). His stories take intriguing turns, like a university lecturer in Belfast who strikes up an uneasy friendship with some retired local toughs, or the retired schoolteacher on a remote (possibly Norwegian) island who uses Skype to keep in touch with his daughter, but they’re almost always rather subdued—less about the events that take place than about the characters’ responses to them. In this guest post, he explains how that approach is rooted in some of the writers he’s most admired.

Despite what others might say, it’s probably not possible to write a short story in Ireland without James Joyce metaphorically peering over your shoulder. In my case he’s actually there, because a small portrait I bought in a local auction hangs behind me on the wall of my writing room. It’s not a shrine and he competes with many other faces and images but I don’t doubt that the influence of his short stories in Dubliners has seeped permanently into my consciousness.

There is the exquisite portrayal of first love’s searing pain in a story like “Araby,” the climactic epiphany in “Eveline” where “all the seas of the world tumbled about her heart.” And of course above all there is the supremacy of “The Dead” that like a stone skims eternally across the creative consciousness and never sinks below the waves, no matter how much time passes or literary fashions come and go.

Beginning with the mundane details of a preparation for a party it moves to establish a social context, then gradually reveals the inner life of the central character until he experiences a life-changing moment that might be called self-knowledge, but in fact is more than this and something for which we have no ready name. The story is constantly rippling outwards until finally it encompasses the universal and time itself with the snow “falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

12 January 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.