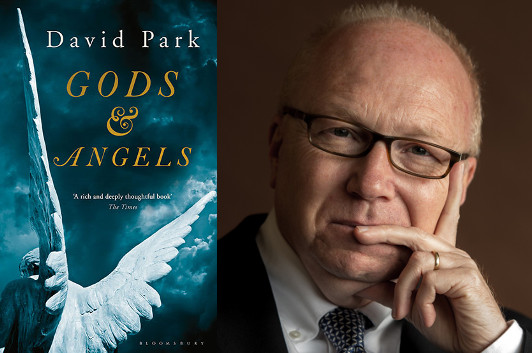

David Park’s Way of Seeing into Lives

photo: Bobbie Hanvey

As I was reading the stories in David Park’s Gods and Angels, I took note of the way he’s able to dig into the emotional lives of his protagonists, whether it’s a teenage boy who’s tired of having to spend the day after Christmas with his estranged (and clinically depressed) mother, or a middle-aged man who’s struggling, during a weekend getaway, to find a way to relate to one of his best mates (who’s also coping with depression). His stories take intriguing turns, like a university lecturer in Belfast who strikes up an uneasy friendship with some retired local toughs, or the retired schoolteacher on a remote (possibly Norwegian) island who uses Skype to keep in touch with his daughter, but they’re almost always rather subdued—less about the events that take place than about the characters’ responses to them. In this guest post, he explains how that approach is rooted in some of the writers he’s most admired.

Despite what others might say, it’s probably not possible to write a short story in Ireland without James Joyce metaphorically peering over your shoulder. In my case he’s actually there, because a small portrait I bought in a local auction hangs behind me on the wall of my writing room. It’s not a shrine and he competes with many other faces and images but I don’t doubt that the influence of his short stories in Dubliners has seeped permanently into my consciousness.

There is the exquisite portrayal of first love’s searing pain in a story like “Araby,” the climactic epiphany in “Eveline” where “all the seas of the world tumbled about her heart.” And of course above all there is the supremacy of “The Dead” that like a stone skims eternally across the creative consciousness and never sinks below the waves, no matter how much time passes or literary fashions come and go.

Beginning with the mundane details of a preparation for a party it moves to establish a social context, then gradually reveals the inner life of the central character until he experiences a life-changing moment that might be called self-knowledge, but in fact is more than this and something for which we have no ready name. The story is constantly rippling outwards until finally it encompasses the universal and time itself with the snow “falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

This I think epitomizes one of the paradoxes involved in the short story form because although it is in some senses reductive, by the end you want it to open itself to a wider vista—for the stone to go on skimming. When I write a short story I am primarily interested in exploring the inner life, of finding what John McGahern referred to as “a way of seeing into lives,” so I’m looking inwards, but by the end I want that gaze to be turned outwards. I admire the way writers like Alice Munro and William Trevor have been able to do this over their long careers and still stay true and fresh. I also admire their capacity for an empathetic tenderness that, to me at least, feels both like a writing and a human strength.

Although I am able to enjoy many styles of short stories and have found recent pleasure in the work of George Saunders I share Raymond Carver’s dislike of “tricks.” I also think it is a bad mistake to confuse cleverness with wisdom. Wisdom is something that might or might not emerge from a piece of work if all its components are perfectly judged but cleverness is often a self-conscious artifice that serves to distract from the work and is intended to draw attention to the writer. And the writer should never be on the page spinning plates—only the world his or her imagination has been able to create.

In Gods and Angels I try to explore the inner lives of men and, I suppose, the seemingly permanent conflict depicted by Hamlet between “this quintessence of dust” and man’s potential to be “admirable in action like an angel! In apprehension how like a god!” It is from the starting place of this stark, age-old dichotomy that the stories seek to set themselves in motion, to send themselves skimming.

12 January 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.