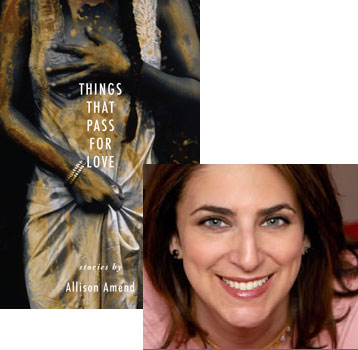

Allison Amend Stares Into “The Aleph”

I first met Allison Amend in the audience at a ceremony for the annual Story Prize, honoring the best short story collection published in America, introduced by a mutual friend. She mentioned she’d written some stories of her; I made a note to keep an eye out for them—and now I’m glad to be able to tell you that Things That Pass for Love is a marvelous collection that can turn from brutal realism with a dash of weirdness (“Dominion Over Every Erring Thing”) to disturbing portraits of emotional breakdown (“Carry the Water, Hustle the Hole”) with the flip of a page. In this essay, Allison celebrates a story which, now that I think of it, brings a disturbing psychological portrait into a story that starts out realistic and quickly gets weird…

There are stories you like and stories you don’t like, but it isn’t until you teach a story that you can really love or loathe it. I discovered this when teaching a course in Magical Realist Fiction, where Gabriel García Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings” went on the nice-story-but-I-don’t-ever-need-to-read-this-again list and Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Aleph” was catapulted to my personal all-time top five canon.

The protagonist of “The Aleph” (who we will later learn, in an almost nonchalant afterthought, is named Borges too) mourns the death of his unrequited love Beatriz, forging a reluctant relationship with her cousin, Danieri. Both are writers; Danieri a hack: “He dealt in pointless analogies and in trivial scruples…. Danieri’s real work lay not in the poetry but in the invention of reasons why the poetry should be admired” while the reader assumes the first person narrator’s erudition indicates his superior literary skills. Danieri then shows Borges his secret muse, the Aleph, viewed through a hole in his basement stairs, “the only place on earth where all places are—seen from every angle, each standing clear, without any confusion or blending.”

Borges the author/narrator, unlike his self-aggrandizing frenemy Danieri, starts describing this experience by first claiming that it is out of the reach of description. ” And here begins my despair as a writer. All language is a set of symbols whose use among its speakers assumes a shared past. How, then, can I translate into words the limitless Aleph, which my floundering mind can scarcely encompass?”

13 October 2008 | selling shorts |

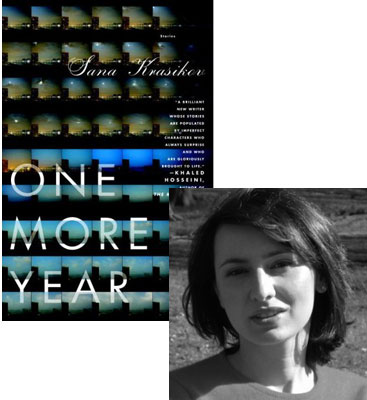

Sana Krasikov: Two Stories Worth the Challenge

Last week, Sana Krasikov was named one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35,” an honor bestowed annually on five young American writers chosen by fiction writers who’ve already been nominated for National Book Awards. And this coming Friday (October 3), she’ll be taking part in one of the first panels of this year’s New Yorker Festival, appearing with Manil Suri and Yiyun Li. And while that buzz might prompt some readers to check out her debut short story collection, One More Year, they’ll stay with it because Krasikov’s characters—often precariously balanced between their old lives in Russia or Georgia and uncertain futures in the United States—are so powerfully drawn. They are not happy stories—but in this essay, Krasikov explains that she draws a different kind of inspiration from short stories that force readers to consider the world from an unsettling perspective.

There is a story by Peter Ho Davies, published in the Paris Review in the summer of 2002 that, if it isn’t yet a classic of short stories, I hope will be one day. Titled “The Ends,” it is no more than two pages long, and narrated by a Nuremberg Nazi war criminal, one of a dozen awaiting execution. From their cells, he and the others listen to the sounds of a basketball game being played by the GIs who guard them. It becomes quickly apparent that the bap bap of the ball is really the hammering of gallows. The men know the Americans are in charge, and that they hang men differently from the British, who follow a mathematical formula of weight per length of rope. The Americans use a standard length so that that “some have their necks snapped swiftly and some strangle slowly.” The ends, Ho Davies writes, are the same, the means different. The Nazis’ darkly humorous survey of execution methods underscores deep divisions between the Europeans and Americans. The Americans believe a standard length is measure of equality and democracy, but Goering, the star war criminal, sees this disregard for scientific rationality as being tantamount to lynching (he prefers the French guillotine, with its elegance and “a touch of the aristocrat”).

Getting the better of his executioners, Goering ends his own life with a cyanide pill, which the narrator of the story believes was obtained from the British who “with their god-like disdain for a scene” hoped to avert the spectacle of a fat man like Goering being decapitated. Moreover, he sees the pill as a symbol of the orderly British’s sympathy with the Germans’ “ends” if not with their means. In a page and a half, Peter Ho-Davies takes a reader from a basketball game to the concealed, split allegiances of whole nations. The story moves quickly from examining Goering’s immediate predicament to contemplating the rhetoric of “efficiency,” which won so many adherents during the 20th century and was used to justify so many of its crimes.

I’m often surprised when I hear readers talk about whether they are “enjoying” a book. The pleasure of reading takes many forms, but the conversations I’m referring to rarely move beyond the likeability of the characters (are they sympathetic?) or the narrative’s emotional tone (does the story offer hope or is it depressing?). Or we read anthropologically—to learn about an exotic culture, or to “get a glimpse” into a closed world. In other words, what’s interesting about the story is the information we take away from it. But such an approach to reading feels so much like one rooted in consumer culture. After all, why read something if it doesn’t have utility for the reader, if it doesn’t make you feel either better or smarter?

29 September 2008 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.