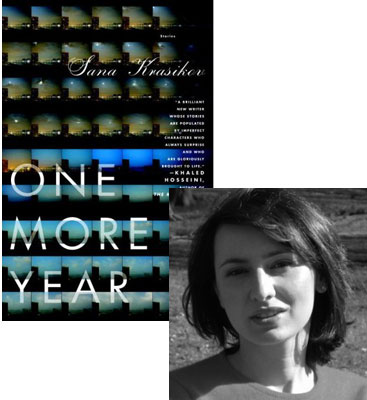

Sana Krasikov: Two Stories Worth the Challenge

Last week, Sana Krasikov was named one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35,” an honor bestowed annually on five young American writers chosen by fiction writers who’ve already been nominated for National Book Awards. And this coming Friday (October 3), she’ll be taking part in one of the first panels of this year’s New Yorker Festival, appearing with Manil Suri and Yiyun Li. And while that buzz might prompt some readers to check out her debut short story collection, One More Year, they’ll stay with it because Krasikov’s characters—often precariously balanced between their old lives in Russia or Georgia and uncertain futures in the United States—are so powerfully drawn. They are not happy stories—but in this essay, Krasikov explains that she draws a different kind of inspiration from short stories that force readers to consider the world from an unsettling perspective.

There is a story by Peter Ho Davies, published in the Paris Review in the summer of 2002 that, if it isn’t yet a classic of short stories, I hope will be one day. Titled “The Ends,” it is no more than two pages long, and narrated by a Nuremberg Nazi war criminal, one of a dozen awaiting execution. From their cells, he and the others listen to the sounds of a basketball game being played by the GIs who guard them. It becomes quickly apparent that the bap bap of the ball is really the hammering of gallows. The men know the Americans are in charge, and that they hang men differently from the British, who follow a mathematical formula of weight per length of rope. The Americans use a standard length so that that “some have their necks snapped swiftly and some strangle slowly.” The ends, Ho Davies writes, are the same, the means different. The Nazis’ darkly humorous survey of execution methods underscores deep divisions between the Europeans and Americans. The Americans believe a standard length is measure of equality and democracy, but Goering, the star war criminal, sees this disregard for scientific rationality as being tantamount to lynching (he prefers the French guillotine, with its elegance and “a touch of the aristocrat”).

Getting the better of his executioners, Goering ends his own life with a cyanide pill, which the narrator of the story believes was obtained from the British who “with their god-like disdain for a scene” hoped to avert the spectacle of a fat man like Goering being decapitated. Moreover, he sees the pill as a symbol of the orderly British’s sympathy with the Germans’ “ends” if not with their means. In a page and a half, Peter Ho-Davies takes a reader from a basketball game to the concealed, split allegiances of whole nations. The story moves quickly from examining Goering’s immediate predicament to contemplating the rhetoric of “efficiency,” which won so many adherents during the 20th century and was used to justify so many of its crimes.

I’m often surprised when I hear readers talk about whether they are “enjoying” a book. The pleasure of reading takes many forms, but the conversations I’m referring to rarely move beyond the likeability of the characters (are they sympathetic?) or the narrative’s emotional tone (does the story offer hope or is it depressing?). Or we read anthropologically—to learn about an exotic culture, or to “get a glimpse” into a closed world. In other words, what’s interesting about the story is the information we take away from it. But such an approach to reading feels so much like one rooted in consumer culture. After all, why read something if it doesn’t have utility for the reader, if it doesn’t make you feel either better or smarter?

A friend once told me about a famous museum curator who, even as an elderly man, would walk up eight flights of stairs to see his wife’s paintings, saying that he had come to them “as a pilgrim.” Subsequent curators never approached her work with the same reverence. They came to examine it as customers. The older curator was a legend in the art world, a refugee from Germany who always wore a hat and bow tie. He was a throwback to an earlier era, where commercial imperatives did not eclipse artistic ones. I wonder how much the language of consumerism has penetrated our attitudes about reading, how much the questions we ask of a book have to do with what it’s supposed to give us, rather than what we bring to it. Do readers have a right to feel entertained, informed, uplifted by what they read? Sometimes. But a book can’t only be evaluated according to those demands. What about a story’s relationship to the larger world? How does it stand as a record of life, of a particular time and place? How does it transform its setting into the private and psychological terrain of its characters?

One author who is acutely aware of this capacity of fiction to pull us in through intimate narratives while commenting on bigger events is Alice Walker. In her story “The Abortion,” Walker describes the erosion of a marriage two years after Imani, a young mother, aborts her second pregnancy. Imani’s husband Clarence is the legal advisor to the town’s first black mayor, whom the media and local business are already scrutinizing for failure. Coming to dine in Imani’s home, Mayor Carswell does not respond to her comments or questions and instead talks to Clarence “as if she were not there.” When Imani takes her daughter to observe a memorial service for a high school girl killed in a hate-crime, her husband and the mayor continue talking out in the church hallway. Sweating in the hot Baptist church, her uterus still burning from her abortion, Imani hisses at them to keep their voices down. Her rage at their fixation with “board meetings” and city politics during a community’s act of bearing witness becomes the seed for her eventual discontent with married life.

As a story, “The Abortion” doesn’t just lay out and resolve the conflicts of its characters. It’s no more a story about a marriage than it is about the intersection of the Civil Rights and Feminist movements. It captures the pivotal moment when women were examining their roles in the Revolution vis-Ã -vis men. It manages to be boldly political without lapsing into political simplicity or tendentiousness. In many ways, Imani is cruel and unjust, making Clarence get a vasectomy—essentially emasculating him—before leaving him. It’s unclear how much Walker’s own sympathies lie with her heroine. But fiction, unlike politics, tolerates such ambiguity and paradox, and in doing so expands our field of vision beyond the story.

29 September 2008 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.