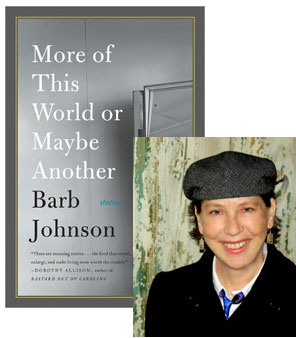

Barb Johnson & the “Magnificent Sadness” of Joyce Carol Oates

Three of the first four short stories in More of This World or Maybe Another feature Delia: first a teenage girl tentatively exploring her sexual identity, then a young woman who thinks she’s shut that experiment down completely, later still a mature woman whose longterm lesbian relationship has hit a major obstacle. Then there’s a passing reference in that last story that makes you realize that “T-Ya,” the small child in the story I haven’t mentioned yet, might be a three-year-old version of Delia—she isn’t, as you’ll discover, but from that point on the connections between her characters grow increasingly intricate. Somebody we’ve seen on the sidelines in one story becomes the “star” of the next, and a character we’ve come to identify with is suddenly re-presented to us from a new angle. In this essay, Johnson—who waited until she was 47 to enter a creative writing program but quickly made up for lost time—revisits a Joyce Carol Oates story about another teenager whose explorations have the potential to pull her life in a new direction.

So I admit it: I like short stories. Sad ones most of all. I like sublime depictions of alienation. And no one is more adept at portraying alienation than Joyce Carol Oates, the queen ruler darling of darkness. While almost all of her short stories offer an impressive portrait of magnificent sadness, one story in particular has really stuck with me over the years. I first read “How I Contemplated the World from the Detroit House of Correction and Began My Life Over Again” when I was maybe twenty, and I have never forgotten the feeling of hidden worlds and worry that it gave me.

In the story, Oates uses a fragmented narrative style to underscore the alienation of the narrator, who is trying to make order out of her own internal chaos. Like all good stories, the individual’s experience here is both influenced by and stands for a larger experience. Oates does a good job of capturing the turmoil and issues of the late sixties, but this is a story of any time and any place. And best of all, it answered a question for me. I had never understood why the daughters of privilege went looking for the very sort of trouble I was trying to make enough money to move away from.

The story takes its form ostensibly from a writing assignment given to the unnamed teenaged narrator. The setting is 1968 Detroit/Grosse Pointe. Despite the fact that there had been a very deadly race riot the year before in Detroit and ongoing rioting across the United States and throughout Europe in 1968, in the notes for her essay, the narrator lists “nothing” under the category of “World Events.” In the girl’s world, the world of Grosse Pointe, there are no events. Trouble is hushed, tucked out of sight. Fixed and forgotten. We learn that the girl has a history of shoplifting. Her older brother has been sent away to boarding school, following a series of—we surmise—increasingly severe crimes.

The “World Events” entry is followed by “Sioux Drive.” The girl gives elaborate descriptions of the houses in her neighborhood where her neighbors are judged by those houses and by their exalted professions. But as with events, nothing much sticks in Grosse Pointe, which has everything it needs and forgets everything it doesn’t want.

When spring comes, its winds blow nothing to Sioux Drive…nothing Sioux Drive doesn’t already possess, everything is planted and performing. The weather vanes…don’t have to turn with the wind, don’t have to contend with the weather. There is no weather.

15 October 2009 | selling shorts |

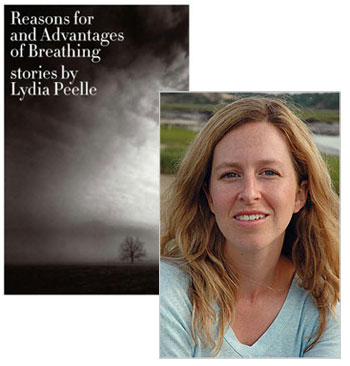

Lydia Peelle, Caught Up in “The Long Rain”

When I got the news about this year’s “5 Under 35” selections from the National Book Foundation, I was delighted to see Lydia Peelle on the list. I’ve been enjoying her debut short story collection, Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing not just for her ability to depict characters who are learning to recognize the pivotal life moments they’re passing through (or, in some cases, passed through years ago), but also for stories like “Phantom Pain” which show the effects of a rumor rippling through a community, brushing up against the other emotional burrs with which people are coping. It looks like New York literati will get a chance to hear Peelle for herself when she comes to the 5 Under 35 celebration in November; until then, this rising writer has graciously shared some thoughts about a short story that moved her in her not-so-distant youth.

I was lucky enough to encounter brilliant English teachers during that tumultuous time of life that is junior high school—and it was with the most brilliant of them all, near-sighted and perspicacious Mr. Hopkins, with his Coke-bottle glasses and rarefied philosophical ramblings (well over our heads, but I’d like to think some of it percolated through), that I first read Ray Bradbury. How grateful I am that I was introduced to this master’s work so early, at such an impressionable time, and by such a wonderful teacher. The book was The Illustrated Man, it was the last semester of 8th grade, and despite the burgeoning distractions of spring, my friends and I feel deeply in love with all things Bradbury.

Though we had read plenty of short stories through the school years, I think The Illustrated Man must have been the first story collection I ever read. For me it opened up an enormous realm of potential. I became aware of the alchemy that exists in great short story collections: how they are greater than the sum of their parts, and how, within their pages, an entire world can be assembled (or, in Bradbury’s case, an entire universe—literally).

The book’s framing premise—that each story is depicted in a tattoo (drawn years ago by a time-traveling witch) on a wandering man’s body and that anyone who looks long enough will eventually see his own death—was just the stuff to capture our attention and imagination. We were just as taken with this framing as we were with the individual stories (all of them still so clearly in my mind to this day, with their chilling and often accurate views of the future as foretold by Bradbury in the middle of the 20th century: “The Veldt,” “The Rocket Man, “Marionettes, Inc.”) and we used to pass notes—in math class or science class, of course, never during English—decorated with our own “illustrated men,” crude blank bodies hastily drawn and filled in with pictures that depicted the drama of our days: this boy, or that teacher, or one of the lunch-hour adventures we were always scheming.

Suffice to say, these stories lodged deeply in my mind and memory, in the way only things one reads when very young do. There is one story in particular that has stayed with me, in high resolution: “The Long Rain,” a deceptively simple story with so much in it from which to learn.

13 October 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.