Barb Johnson & the “Magnificent Sadness” of Joyce Carol Oates

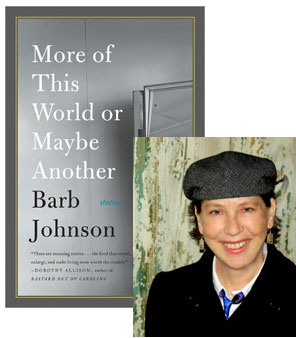

Three of the first four short stories in More of This World or Maybe Another feature Delia: first a teenage girl tentatively exploring her sexual identity, then a young woman who thinks she’s shut that experiment down completely, later still a mature woman whose longterm lesbian relationship has hit a major obstacle. Then there’s a passing reference in that last story that makes you realize that “T-Ya,” the small child in the story I haven’t mentioned yet, might be a three-year-old version of Delia—she isn’t, as you’ll discover, but from that point on the connections between her characters grow increasingly intricate. Somebody we’ve seen on the sidelines in one story becomes the “star” of the next, and a character we’ve come to identify with is suddenly re-presented to us from a new angle. In this essay, Johnson—who waited until she was 47 to enter a creative writing program but quickly made up for lost time—revisits a Joyce Carol Oates story about another teenager whose explorations have the potential to pull her life in a new direction.

So I admit it: I like short stories. Sad ones most of all. I like sublime depictions of alienation. And no one is more adept at portraying alienation than Joyce Carol Oates, the queen ruler darling of darkness. While almost all of her short stories offer an impressive portrait of magnificent sadness, one story in particular has really stuck with me over the years. I first read “How I Contemplated the World from the Detroit House of Correction and Began My Life Over Again” when I was maybe twenty, and I have never forgotten the feeling of hidden worlds and worry that it gave me.

In the story, Oates uses a fragmented narrative style to underscore the alienation of the narrator, who is trying to make order out of her own internal chaos. Like all good stories, the individual’s experience here is both influenced by and stands for a larger experience. Oates does a good job of capturing the turmoil and issues of the late sixties, but this is a story of any time and any place. And best of all, it answered a question for me. I had never understood why the daughters of privilege went looking for the very sort of trouble I was trying to make enough money to move away from.

The story takes its form ostensibly from a writing assignment given to the unnamed teenaged narrator. The setting is 1968 Detroit/Grosse Pointe. Despite the fact that there had been a very deadly race riot the year before in Detroit and ongoing rioting across the United States and throughout Europe in 1968, in the notes for her essay, the narrator lists “nothing” under the category of “World Events.” In the girl’s world, the world of Grosse Pointe, there are no events. Trouble is hushed, tucked out of sight. Fixed and forgotten. We learn that the girl has a history of shoplifting. Her older brother has been sent away to boarding school, following a series of—we surmise—increasingly severe crimes.

The “World Events” entry is followed by “Sioux Drive.” The girl gives elaborate descriptions of the houses in her neighborhood where her neighbors are judged by those houses and by their exalted professions. But as with events, nothing much sticks in Grosse Pointe, which has everything it needs and forgets everything it doesn’t want.

When spring comes, its winds blow nothing to Sioux Drive…nothing Sioux Drive doesn’t already possess, everything is planted and performing. The weather vanes…don’t have to turn with the wind, don’t have to contend with the weather. There is no weather.

However, when the girl describes Detroit, which she has skipped school to visit, where she has been passed around and sampled by a group of junkies, she gives quite a different description.

There is always weather in Detroit. Detroit’s temperature is always 32 degrees. Fast-falling temperatures. Slow-rising temperatures. Wind from the north-northeast…hazardous lake conditions for small craft, for swimmers, restless Negro gangs, restless cloud formations, restless temperatures aching to fall out the very bottom of the thermometer or shoot up over the top and boil everything over in red mercury.

A new “friend,” Clarita, wonders aloud why girls like the narrator bum around Detroit. “What are you looking for anyway?” she asks. What the narrator is looking for is weather, and she finds it. Cops raid her junkie lover’s apartment, and the narrator gets blown into the Detroit House of Corrections where a couple of the other girls beat her mercilessly, venting “the hatred of a thousand silent Detroit winters…revenge on the oppressed minorities of America! revenge on the slaughtered Indians, revenge on the female sex, on the male sex, revenge on Bloomfield Hills [neighborhood set ablaze during race riot], revenge revenge…”

When the girl’s parents take her home to Grosse Pointe, they make it clear that the family will proceed as though nothing has happened. At her fancy day school, the “event” goes unmentioned. In the morning, the girl will start again clean and new: “Sugar donuts for breakfast. The toaster is very shiny and my face is distorted in it. Is that my face?” (A classic Oates line: “Is that my face?”)

While the narrator, now physically and emotionally bruised from her Detroit experience, insists that she is home, that this is her home, that she will never leave it again, the reader doubts it. More likely, this is the first of many trips the girl will take in order to find more weather for her static existence. She has absorbed the blows that the streets of Detroit delivered. And though she would seem, as the title suggests, to be starting her life over in the clear, calm of Grosse Pointe, it is unlikely that this single burning event will cauterize the festering alienation that sent the girl out in search of trouble—in search of life—in the first place.

15 October 2009 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.